The area of Ossett forming the south-eastern boundary with Horbury at Spring End is known as Ossett Spa. This is a reference to the natural springs that provide a perpetual supply of water and whose health-giving properties were seized upon by 19th century entrepreneurs keen to promote the area as a Little Harrogate or perhaps a Yorkshire version of Cheltenham Spa. James Ward and William Craven built the competing Cheltenham Sulphurous Baths and the New Cheltenham Baths on almost adjacent sites off Spa Lane in the early part of the 19th century. Ossett Spa Mill, which was built in the 1860s opposite the site of the New Cheltenham Baths had a mill dam fed by a natural spring The natural spring is still there today and feeds a pond in the back garden of the bungalow owned by Mr. John Myers.

However, the history of Ossett Spa goes back before the Little Harrogate schemes to the late 18th century with the building of Spring End Mill, one of the earliest scribbling and carding mills in Yorkshire by Ossett resident John Emmerson. Ossett Spa also played host to an 18th century colliery owned by the Naylor family and Jefferey’s 1775 map Of Wakefield shows the “Black Engine” used to pump water out of the mine workings.

Later still, there was an influx of miners to the area from places like Barnsley and Wakefield to work at nearby Roundwood Colliery. Although first opened in 1847 as a small day hole enterprise, Roundwood was massively expanded by the Greaves family towards the end of the 19th century as a deep mine colliery. It was reckoned that by the year 1900, close to 1,000 men were employed at Roundwood, many of whom made their homes close to the pit in the Ossett Spa area.

Goring House, Ossett Common, once the home of Ossett author Stan Barstow, is virtually all that remains of an ambitious project at the end of the 19th century to develop part of Ossett Common as the “New Montpellier Pleasure Gardens”, likened to a Little Harrogate by Batley Carr entrepreneur and former drugget manufacturer, Mathew Wharton. Goring House was built by an associate of Wharton’s, John Tennant, a Dewsbury property developer and auctioneer who committed suicide in one of the bedrooms of Goring House in April 1888 after he also encountered severe financial difficulties.

Goring House was once the home of Ossett novelist Stan Barstow and was also previously owned by John Tennant, James Butterworth, Joe Bentley and Alfred Kilbank. For a while the house was converted into two flats.

The original owner of Goring House, John Tennant committed suicide in 1888 after getting into financial difficulties (see below). In 1896, Goring House was occupied by James and Stella Butterworth. James was an athletic goods manufacturer, making athletic, cricket and lawn tennis goods at premises in Manor Road, Ossett.

Another owner of the house was Joseph William Bentley, an Ossett mungo manufacturer with premises at Ginns Mill or Hope Mill, Ossett Spa. He the younger brother of two times Ossett mayor Thomas Wilby Bentley. Joe Bentley married in his late 40s and probably moved to Goring House sometime after 1911 when at that time he was living at Clarendon Road, Ossett.

Bingley born Alfred Kilbank (pictured left) was the Managing Director of Pickles, Ayland and Company, paint manufacturers and contractors who were based at Sowdill Works, Ossett. It is thought that he lived at Goring House until his death in 1952.

The little Harrogate scheme, to which Goring House stands a a single memorial seems first to have been mooted in 1879. In January that year, the “Ossett Observer” reported:

“It was informed on reliable authority that the first section of a project for transforming Ossett Spa into a second Harrogate, as a summer residence for visitors, is to be immediately carried out. Land has already been purchased, several acres in extent, and the services of an experienced architect engaged to lay out the same into sites for residences, boarding houses and other buildings of a public character. The whole of the streets are to be planted with trees in the continental style.”

The lime trees, which still form avenues in Goring Park Avenue and the adjoining streets were planted in 1864, but advertising of the sites for villa residences “to be purchased over a period of six years on a quarterly installment plan” seems to have had no takers and only Goring House stands as a reminder of the ambitious scheme to develop this part of Ossett.

In 1884, part of the Spa estate land was taken over by a Batley Carr manufacturer, Mathew Wharton, with the aim of developing it as the New Montpelier Pleasure Grounds with extensive gardens, a boating lake, rides and amusements. There was an advertisement in “The Era”, a London Newspaper on March 22nd 1884, as follows:

“WANTED – Violins, Flute, Double-Bass and a complete orchestra. Six-month season commencing on Good Friday (rehearsal, Thursday, April 10th) for the New Montpellier Gardens, South Ossett Spa. Apply, stating terms to J.W.R. Binns, 78 Reuben Street, Leeds.”

A public entertainment was staged in Ossett over the Easter holiday in 1884 when the main attraction was the “African Blondin”, one Carlos Lamentine Trower of American or Puerto Rican origin. Billed as the “Prince of the Air”, he performed with a number of other variety acts of the time. Trower had moved to England and married Annie Frances Emmett at Barnstaple in 1875. He had a fixed contract as a “funambulist” at the Rotherville Gardens in Essex from 1881-1886 and appeared at Foresters, Chatham Recreation Grounds, Kent in 1882. Trower died in the Grove Hall lunatic asylum, Bow, London in 1889.

Sadly, the venture was no more successful than the rest of the “Little Harrogate” schemes and by June, Wharton was bankrupt. Wharton had a history of financial failures in the textile and entertainment businesses, including the loss of £1,000 leasing a pier on the Isle of Man. The first notices appeared in the local press by July 1884 1 :

“IN BANKRUPTCY – Notice is hereby given that Mathew Wharton, Jun., of Upper Road, Batley Carr, Dewsbury and Montpellier Gardens, Ossett Spa both in the County of York, was on the 10th day of July, 1884 adjudged bankrupt by the County Court of Yorkshire holden at Dewsbury – John Arthur Deane, Official Receiver.”

At the subsequent bankruptcy hearing held in August 1884, Wharton’s less than honest dealings with John Tennant were first revealed: 2

“The next examination was that of Mr Mathew Wharton, who has from some time back entered into rash speculations as a public entertainer. The debtor resides at Batley Carr. In reply to the Official Receiver, he said that from 1880 up to a fortnight before Easter, he had carried on no business. He was formerly a drugget manufacturer and when he ceased in 1880, he had a capital of £8,000, which he invested in property. He then went to the Isle of Man and lost £1,000. Since he gave up business as a manufacturer, he had kept no books except rent books. He sold his furniture at the latter end of April 1884 and went to live in a less house. He had had two sales of furniture. The one in April realised £70. It was sold to John Tennant. His father died in 1880 and left him £6,000 and at his mother’s death £800 came to him. The debtor was examined by Mr. R.W. Evans, solicitor, respecting the failure of his last speculation, the Montpellier Pleasure Gardens, Ossett and the disposal of various articles connected therewith, for which he owed money to various tradesmen and admitted having sold goods which cost £300 to John Tennant for £36. He did not know where Tennant was, but he had told him that he was going to the south of England. The examination was adjourned and a restraining order was granted against Tennant to prevent him from selling a dancing platform and other fixtures in his possession.”

Suicide

Goring House was the only villa residence to be erected as part of the Little Harrogate scheme and was built by a man named John Tennant, who was possibly also the promoter for the Little Harrogate and New Montpellier Gardens project and had bought into Mathew Wharton’s big scheme. Tennant was a colourful character who started off in life as a joiner and builder in Dewsbury, but went into property speculation in a serious way. He was also in partnership with a Leeds man called Leon Gross in a money-lending business until the partnership was dissolved in 1888.4 Tennant was also in a partnership with a man called Oldroyd as “Tennant & Oldroyd, Auctioneers” in Dewsbury.

Interestingly, Tennant had been in trouble with the local magistrates in 1886, which might give an insight into his character: 3

“At Dewsbury on Thursday, Mr. John Tennant an auctioneer and large property owner, was fined £20 with the option of three months imprisonment for letting some of his house properties for immoral purposes. It was shown that the houses were of the worst possible character and Tennant’s knowledge of the use to which they were put was proved to the magistrates satisfaction.”

Tennant’s method of paying his creditors had been to give them plots of land on the Ossett Spa Estate. The ensuing obscurity of ownership led to large areas of the land being left derelict up to at least the 1980s. By April 1888, 49 year-old Tennant was in serious financial trouble and committed suicide in one of the bedrooms of his residence at Goring House: 5

“SAD DEATH OF DEWSBURY GENTLEMAN – Mr John Tennant, a retired joiner and builder, late of Dewsbury, where he is well-known as a property owner, was found dead in his bedroom at the Spa, Ossett yesterday morning. The deceased gentleman got up to light the fire and shortly afterwards returned to his bedroom, telling his wife that he had done so. Mrs. Tennant afterwards went downstairs, leaving him there and about a couple of hours later, as he did not make an appearance, she went to seek him. His bedroom door was locked and eventually assistance was obtained to burst it open. The deceased was then found hanging from the top of the bedstead with a piece of clothes line round his neck and quite dead. He was forty-nine years of age. At the inquest last evening, it was stated that the deceased gentleman was strong and healthy, but since Christmas last had been in low spirits, having had trouble in his business and lost a great deal of money. In his pocket was a letter dated the previous day to his son John Thomas Tennant:- “Dear Son – This is more than I can bear. I blame no-one but myself. Forgive me, and do the best you can for yourself, mother, Clara, Sarah-Ann, and lastly Emily. – Your father in trouble, John Tennant.” A verdict was returned in accordance with the facts.”

The medicinal springs in the neighbourhood of Goring House, from which Spa Street, Spa Croft Road and Spring End Farm take their names, were developed commercially earlier in the nineteenth century. For a number of years in the nineteenth century, the workhouse in Horbury was supplied with water from the Spa.

Research by John Goodchild, reveals that James Ward (1746-1832), a Horbury stonemason was awarded land at Low Common at the time of the Ossett Inclosure (1807-13) and he was the first to recognise the restorative properties of the water. There were two separate public bath establishments at Ossett Spa, although it isn’t known exactly when Ward opened the “Ossett Baths” later called the “Cheltenham Sulphurous Baths”, they were still owned by him when they were offered for let in 1829.

Ward’s baths were described in the advert as follows:

“The premises are delightfully situated and the waters have been analysed by several eminent men and spoken of by them as a little inferior to Cheltenham. They have gained a very high reputation from the many surprising cures they have performed. These waters are celebrated for curing gout, rheumatism and the scrofula.”

This advertisement appeared in the “Ossett Observer” 14 in 1864 for the original baths, but presumably by now rented to George Shaw, but probably owned by John Chappell:

“MINERAL BATHS – The original Ossett Spa Baths are open daily from 8am to 8pm. The waters are recommended by the faculty for Scorbutic and Rheumatic complaints. Sulphurous baths 1s 3d; Hot baths 1s; Cold baths 6d. Every accommodation in Refreshments, Beds and Stabling. Proprietor: George Shaw.”

Things had moved on again by 1873 and the “Old Original Cheltenham Bath” had recently been refitted with new baths and cisterns and was being offered for sale in the “Ossett Observer” 15 complete with a stable, coach-house and greenhouse by the then proprietor John Chappell, who was retiring because of ill-health.

The ‘”Cheltenham Sulphurous Baths” were operated from 1864 by John Chappell and then subsequently by Henry Nettleton, and was offered with a number of cottages, cottage garden and an orchard, for auction following Chappell’s death in 1884. The auction was described in the “Ossett Observer” 16 and included, besides the baths, two dwelling houses, a grocer’s shop, nine cottages and four parcels of land.

An advertisement in the “Ossett Observer” 17 tells us about the new proprietor of the old baths after the auction had been completed:

“Re-opening of the Old Cheltenham Sulphur Bath by J. Marsden, proprietor of the Wakefield Turkish Baths. Slipper and sulphur baths 6d each. Refreshments and stable accommodation available.”

The second and competing bath house at Ossett Spa was called the “Spring End” or “New Cheltenham Baths” and dates back to 1823 when it was established by William Craven of Horbury. By 1826, the New Cheltenham Baths were tenanted (but not owned) by David Land. An advertisement 7 from that time describes the baths as follows:

“Consisting of medicated vapours, sulphurous, sitting, shower or plunge baths, with a separate establishment for the poor at a reduced rate.”

Land seemed to be doing well and the baths were clearly well patronised 8:

“D. Land proprietor of the New Cheltenham Baths is grateful for the support last summer and that cold, warm and shower baths were available. Accommodation is also available in respectable houses in the neighbourhood.”

The last comment is interesting and it seems likely that Land had premises adjoining the New Cheltenham Baths where people could stay and take the Ossett Spa waters or enjoy the apparent health-giving properties of his baths. This was common in other Spas, such as Askern, Harrogate or Cheltenham and it is likely to have influenced later generations who sought to develop the area as a “Little Harrogate“.

In 1831, it is believed that David Land bought the baths and they were advertised 9 for sale in the local press and were described as follows:

“FOR SALE – New Cheltenham Spa and Baths and four dwelling houses, now or lately occupied by William Willison, Edward Moulson, Joseph Chappell and others. The premises recently fitted up and contain two china baths, one china sitting bath, two cold baths, a shower bath and a plunging bath with new cisterns and boilers.”

A further advertisement 10 a few weeks later gives us an idea of the cost of using the baths:

“New Cheltenham Baths – D. Land, opened for the season on the 1st May 1831. Annual subscription available for bathing: one person to the warm and cold baths, 10 shillings. For a family to the warm and cold baths, £1; sulphurous baths each 2 shillings. Board and lodging available at the bath house.”

By May 183212, Land had bought both of the competing Ossett Spa bath houses, which it is stated actually adjoin each other. This advertisement in the local press relates the announcement:

“OSSETT SPRING END CHELTENHAM BATHS – D. Land in occupation for the last six years has taken the adjoining bath establishment with medicated vapour, warm, sulphurous, sitting, shower and plunge baths. A separate establishment is provided for the poor at reduced rate. Board and lodging available. W.B. Thornton, M.D. attends the baths, Monday, Thursday and Saturday to give advice. Medicated vapour baths 3 shillings; sulphurous vapour baths 2 shillings; warm and shower baths 1 shilling; cold and plunge baths 6d.”

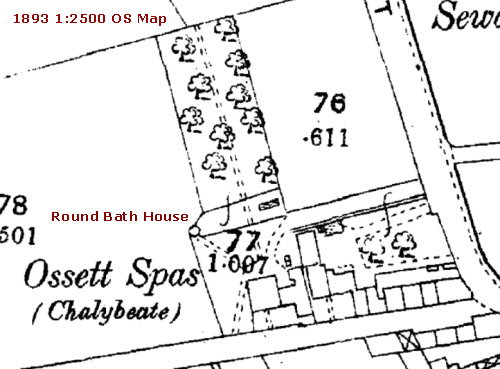

The baths were extensively used by Ossett people and one Ossett man described how the baths helped his rheumatism13, but that only married couples were allowed to bathe together. Land’s circular bath house had a well in the centre (see pictures below of the derelict bath house) where bubbling water could be seen. A large house (most probably Spa House) was built to accommodate those people visiting to take the waters.

By 1849, it seems that the two Ossett Spa bath houses were once again in separate ownership and the New Cheltenham Baths were owned by a man called Ezekial Goldsmith. The baths were offered for sale by his widow after his death aged 64 in early 1877. However, the baths had been offered for sale earlier in 18536 and the advertisement gives us a good description of the premises:

“FOR SALE – All that messuage, tenement or dwelling-house situate on Ossett Common, with the Spa House, hot and cold baths, boiler house, stable and other buildings to the name belonging, called “THE NEW CHELTENHAM BATHS” also the close of land and garden adjoining thereto and the private road leading therefrom into the Horbury and Ossett road, containing together, including the sites of the buildings 1 acre, 0 roods, 3 perches or thereabouts and now in the occupation of Mr. E. Goldsmith. The celebrated spa well from which the baths are supplied is on this lot. The water was analysed some years ago by the late William West, F.R.S. and was found to be very similar to the waters at Cheltenham.

The baths, which were established upwards of 30 years ago by the late William Craven, Esq., of Horbury are much resorted to by persons suffering from rheumatic affections. They have also proved highly efficacious in all complaints and in cases of general debility. The baths are capable of considerable extension and improvement and will be found to be a lucrative investment.”

People living in Ossett Spa still collected bottles of the spa water for their own consumption right up to the 1920s. A single small circular stone bath-house is still just about standing behind what used to be Illingworth’s fellmongers. The wall of the bath-house was over five feet high until 1990, when the then owner J.T. Watson reduced it to around 18 inches and installed an iron gate across the entrance. The site was then bought by Alan Morris.

Left: The only remaining bath-house at Ossett Spa containing the mineral spring that used to feed the mill dam at Illingworth Bros. fellmongers. This picture was taken in the 1970s. The mill dam, with the ducks in the picture above, at Illingworth Bros. was built after WW2 and is first shown on the 1955 OS map as a “tank”.

In 1896, Albert Illingworth set up a fellmongering business (taking the wool from sheep pelts) in buildings adjacent to the bath house pictured above, so that he could utilise the ample supply of water. One of the same Illingworth family was still running the business when it finally closed down in 1986. Later occupants of the site capped the well and demolished the walls of the bathhouse. They also drained the pond to extend the size of their car park. Sadly, important Ossett history erased for ever. 11

It had been feared in 2007 that the entire site would be levelled since the site has been earmarked for a new warehouse by developers Niels Larsen. Sadly, there is still much confusion about the land boundaries and this important reminder of Ossett’s heritage may soon be lost forever.

However, by March 2008, the land dispute had been resolved and the land that the bath house stands on was given to the owners of Spa Farm, who have taken steps to make sure that the site is preserved. Work is now in progress to fence off what is left of the Ossett Spa to prevent damage from horses kept in adjacent fields and to allow access for visitors accessing the site from Spa Lane.

Left: This is what is left of the old bath at Ossett Spa in September 2010 (Photograph by Alan Howe). The height of the walls has been reduced to about 18″. The land is now owned by the Skinner family, who in 2010 cleared the site with a view to reinstating the spring water well inside the demolished bathhouse. The Nils Larsen warehouse can be seen to the right of the picture, built over the site of the Illingworth Brothers dam, which can be seen in an earlier picture above.

Left: The remains of the Ossett Spa bath ten years later in February 2020 (Photograph by Rachel Driver) after the site was cleared of weeds and brambles that had virtually covered the old bathhouse.

Ironically, the presence of its spa waters in the many wells and springs in the area seems to have had less permanent effect on the development of Ossett Common than the opening of Roundwood Colliery, which brought an influx of miners from Barnsley and Featherstone to settle in the area.

Until the 20th century, the typical miners dwelling was still the low stone croft cottage. At Ossett Spa, a miners cottage has recently been restored (see below). In a survey of the living and working conditions of Yorkshire miners made in 1841, the inspectors describe the cramped conditions of large families living in similar cottages, usually consisting of just two small rooms.

The earliest recorded scribbling mill in Ossett and one of the earliest in the West Riding of Yorkshire was built in the Spring End area of Ossett Spa in about 1780 by Ossett master handloom weaver, John Emmerson and his partner Joshua Thornes, an Ossett worsted cloth manufacturer. By 1782, the partnership of the mill was extended to include James Mitchell and John Oakes, both Ossett master clothiers.

Mitchell, Oakes and Emmerson are listed in the Ossett Rate Books as tenants of the mill and Emmerson also owned the surrounding land as well as the site of the mill itself. Thornes was never a tenant of the mill and it is likely that he was just an cash investor in the mill enterprise, which was leading edge technology at the time. Joseph Thornes died in October 1838 aged 85 years and his shares in the mill were sold.

The mill is described in the 1813 Ossett Inclosure Order as Emmerson’s Mill but was more commonly known as Spring End Mill and then later as Spring Field Mills (bottom right on the map below) and cost £343 17s 8d to build, it is thought in 1779 or 1780. The partners each managed the mill one year at a time:

1781-82 – James Mitchell

1782-83 – John Oakes

1783-84 – James Mitchell

1784-85 – John Emmerson

The partners were probably more skilled at producing cloth than they were at keeping financial accounts and disaster struck in 1785 when John Oakes was declared bankrupt with total liabilities of £127 5s 10d. A Wakefield solicitor had to be employed by the partners at Spring End Mill to convert their crude financial records into an appropriate business accounting system. These records show that five shillings a year was paid for rent for the use of the mill goit that was built to turn the water wheel, which powered the early mill machinery. John Emmerson received £25 per annum for the rental of the mill premises.

Spring End Mill did well with a income of £63 18s 2d in the year up to August 1784. This was made up from £7 16s 6d earned from willeying and a healthy £55 17s 8d from scribbling, of which 25% was work done for external customers and the rest on behalf of the individual partners. Compared to the original £343 cost for the building the mill, it can be seen that an income of £64 a year was a significant return on investment. However, outgoing costs were £72 14s 0d in the same period in 1784, and would have been for the purchase of oil, candles, resin and coals for the mill as well as for staff wages. However, the partners should have been able to make a reasonable profit after the sale of the cloth, which had been processed in the mill, was added to their income stream. In 1786, the water course was widened, giving a better flow of water, then the willeying machine was repaired and recovered in cards, which resulted in increased income of £14 7s 3d for willeying operations.

In 1791, another mill was built at Spring End, just across the Horbury boundary, whose main purpose was the fulling of cloth, as opposed to scribbling and willeying at Emmerson’s mill just across the boundary in Ossett. The main problem was that the water course, which powered Spring End Mill was not potent enough to power both mils, which were almost geographically adjacent. The amount of fall (land gradient) between the two mills was very small and so the water course for both the water wheels was really not adequate, particularly in times of drought.

Always forward thinking, Emmerson and his partners commissioned a new steam engine and this was installed in 1797, solving the problem of a sustainable power source for Spring End Mill. In addition, they also started fulling cloth at the mill in direct competition with the new upstart mill over the Horbury boundary.

In March 1798, David Emmerson (probably a close relative) of John Emmerson) agreed to sell his share in the “Spring End Mill Fire Engine and all its Appurtances” to another Ossett clothier, David Dews for the sum of £200. In the following year (1799), Dews was one of six Ossett clothiers who formed a partnership with John Emmerson and agreed to work “all that large building or scribbling mill called Spring End Mill”, near Ossett Common, with “the dam, goit, watercourses” and some 3.75 acres of nearby land, which was occupied by the partners. Use of the steam engine to power the fulling stocks and mill machinery was included plus the use of a drying house as well. However, the steam engine and machinery were owned by the co-partners rather than Emmerson who was the landlord. Shares in the partnership were in sixteenth parts, but with most partners holding two shares each, i.e. one eighth share. The agreement was for a period of eighteen years and the partners paid an annual rental of £95-10s-0d to John Emmerson. In December 1800, a one sixteenth share was sold to the trustees of Miss Frances Eastwood of Horbury, for £150 with one of the trustees being James Eastwood who owned the competing mill over the border in the town of Horbury.

John Emmerson, a yeoman, was most likely born in Wakefield in 1751 and married first Grace Mitchell in 1771 and then his second wife, Sarah Wood at St Peter’s Church in Horbury on the 5th July 1804. In 1813 as part of the Ossett Inclosure Act, Emmerson was awarded the land in the Ossett Common area and also the site of the mill dam, which encroached into the Manorial Estate of Wakefield.

By 1821, Spring End Mill was being worked by Benjamin Emmerson and Co. Benjamin was presumably one of John Emmerson’s sons, but the relationship has not been proven yet. After John Emmerson’s death (date unknown), his executors let the buildings at Spring End Mill to Wheatley, Overend and Collett, who in 1834 employed 22 males, 17 males and probably several others as well. Of these employees, 19 were under the age of sixteen years.

An 1837 rating valuation describes the “mill with engine house, willeying rooms, drying house, etc.” and suggests some extensions were taking place “the newer part not being finished, is not valued.” For a time in the 1840s, the mill stood empty, but was occupied again in 1847 as a scribbling and fulling mill after being bought by Thomas Phillips. After Phillips’ death in 1851, Spring End Mill and three acres of land was again offered for sale. Later on in 1856, the mill became the subject of a Chancery Court action between Messrs. Butterworth and Riley and as a consequence was offered for sale in with four other lots, which included the nearby Fleece Hotel and five acres of land, all the mill machinery and a two acre plot of land at Little Bircher Hill Royd, Ossett.21 The mill was described in the advertisement as:

“A stone and brick-built mill, covered with grey slate, partly two storeys, partly three storeys high with engine-house, boiler house, warehouses adjoining, known by the name of ‘Spring-End Mill’, situate at Spring-end in Ossett aforesaid, with an excellent condensing steam engine of 30 horse-power, boiler of 40 horse-power, shafting, going gear, steam pipes, gasometer and fittings in and about the premises.”

At this stage, the mill may have been bought by James Marchent, who definitely had ownership of Spring End Mill in the mid 1850s. Earlier, in May and June 1856 22 & 23 machinery at Spring End Mill was offered for sale after the bankruptcy of one of the tenants. By 1861, the mill now manufactured cotton cloth having been bought by the Bacup-based and snappily named “Lancashire and Yorkshire Cotton Manufacturing and Mining Company.” The original partners of this new venture were all Bacup men, with the exception of David Lee, a manufacturer based at nearby Earlsheaton. The company was registered in 1860 and formed for the “spinning, weaving and manufacturing for sale, raw cotton, silk and yarn”, in this case at Ossett Spa, but with business interests elsewhere. In addition, the company was to “establish a gasworks to light local mills and would acquire and work coal or other mines.” The company was still working Spring End Mill in 1867 and the new owners had added another new twenty-five horse-power steam engine in 1860.

By January 1869, the mill was let to John Robinson as a worsted spinning mill. Robinson had earlier had been the principal at Silcoates Mill in Wakefield. He gave up the tenancy in June 1871 and the mill was sold to Henry Oakes, a worsted spinner who had earlier been in partnership at Flanshaw Mill in Wakefield. Oakes’ machinery at the mill was advertised for sale in January 188224 and the next occupier, Albert Mitchell (as M. Mitchell and Sons, mungo merchants) went bankrupt during the great depression in 1884. His machinery was advertised for sale in March 1884.25 A longish period of disuse seems likely before the mill was acquired in the 1890s by Jessop Brothers, who were involved in the manufacture of mungo from rags. By 1900, Jessop Brothers joined the new Extract Wool and Merino Co. Ltd. and in later trade directories Spring End Mill was referred to as Springfield Mill.

One yet unexplained reference to Spring End Mill is a it being called “Black Engine Mill” in the “Ossett Observer” In 1883.26 As yet, the reason for this curious name has not been discovered. The mill was extended significantly in the 20th century with the addition of sheds and is still in existence today as part of a thriving industrial estate. Springfield Mill now has a shop fitting company, an electrical retailer, a tropical aquatics shop, an alternate medicine shop, a carpet fitter, a commercial printer and for the more adventurous an adult “sauna”. I suspect that the original partners would be surprised at the sheer diversity of businesses on offer at Spring End Mill in 2010.

Ginn’s Mill or Hope Mill, Spa Street

The mill was built between 1819 and 1823 by Joseph Brooke who was the first owner-occupier. Brooke produced worsted woollen cloth at the new three-storey mill, which we can speculate was first called Brooke’s Mill. Around 1830, Brooke died and his wife Jane Brooke carried on the business in her won right until 1832 when the mill was put up for sale. The ownership us unclear at this stage and it may be that the mill was tenanted by Joseph Rhodes, but Mrs. Brooke retained full ownership.

By 1843, the mill had been sold to corn miller Joseph Ginn, who in the 1841 census was aged 51 years and living in Low Common, Ossett with his family. Ginn operated a steam-powered corn milling business from the mill and the first O.S. Maps from the 1850s name the mill as Ginn’s Mill. By 1850, the mill was for sale in the local press:

“TO BE SOLD BY PRIVATE CONTRACT, all that capital steam mill, now used as a corn mill, with the messuage or dwelling-house, outbuildings and close of grass adjoining, all which premises are situate at Ossett Common, near Wakefield, and contain an area of 2 acres, 2 roods, and 2 perches or thereabouts, and are now in the occupation of Mr. Joseph Ginn, corn miller. The premises are freehold and are well supplied with water. The mill is in excellent repair and is fitted up with every requisite for a complete corn mill, and may at trivial expense, be converted into a woollen or worsted mill.”

Joseph Gomersal, a maltster from the Spen Valley area bought the mill in 1850 and continued to run the business as a corn mill until 1865. Both Ginn and Gomersal may have sub-let the premises or used contractors at the corn mill and in 1856 Edward Walshaw was running the corn mill. The 1861 census records Edward Whitaker, corn miller, living adjacent to the Fleece Hotel and two doors away is James Fryer, also a corn miller, but employing three men, one of whom may have been Whitaker.

Horbury-born cloth manufacturers Henry Giggle and William Brook with George Teal, a wool sorter from Bradford purchased Ginn’s Mill in December 1865. The new owners changed the use of the mill to a flock manufactory, which previously had been Giggle’s trade. Henry Giggle had dissolved a business partnership with John Leech Barber in May 1865 19 and previously the two of them had been trading as a Giggle & Barber, Flock Manufacturers in nearby Horbury

By 1872, the mill was again offered for sale in the local press 20 together with two houses then occupied by Henry Giggle and George Teal, whose occupation is now given as a painter. In addition the sale included a 1200 square yard area of “garden land”, occupied by John Fletcher, which was probably a smallholding, fronting the main road at Spring End a few hundred yards from the mill.

A fire damaged the mill in May 1887 27 and William Brook’s subsequent planning application for two rag machine rooms was approved by the Ossett Local Board of Health. In November 1887 28, wool extractor William Brook was declared bankrupt and it was noted at the subsequent creditors’ meeting that he had been in business for twenty-five years and that he had been insolvent in 1876. Perhaps this was why he was not named in the sale particulars in 1874?

By 1889 Albert Metcalfe and Co. occupied the mill as tenants of the Wakefield and Barnsley Bank and were operating a reclaimed wool business. In December 1905 29 an action was brought by Messrs Bentley Bros. of Hope Mill, mungo manufacturers, at the Leeds Assizes against Messrs. Metcalfe & Co. also mungo manufacturers of the same address. Bentleys were seeking to recover £202 compensation from Metcalfe which they (Bentleys) had paid to the widow of their employee, John Henry Dews,who had been killed at the Mill on 1st April 1905. Dews had been killed by the bursting of a drum in an engine (used to power the rag machine) that was known to be faulty and had a tendency to “run away” (i.e. speed up and shake uncontrollably). Bentleys rented a room, a rag machine and power from Metcalfe. Bentleys claimed that they were entitled to rely on their tenancy agreement that the engine was safe and that any maintenance was Metcalfe’s responsibility so consequently, it was they who should also be responsible for widow Dews’ compensation. In the event, the Court found in favour of Bentley.

The report also tells us that Metcalfe and Co. were themselves renting the mill from the Wakefield and Barnsley Union Bank on a ten-year lease from October 1902 at £100 per annum. Bentley took out a lease from Metcalfe in the same month. The engine had been installed in July 1902. The head of Messrs. Metcalfe and Co. was Mr Albert Metcalfe and he stated that the firm had taken possession of the mill in 1888.

In May 1907 the mill was offered for sale by auction by the United Counties Bank by which time Metcalfe and Co. were paying a rent of £105 per annum. 30 By 1910 Albert Metcalfe is recorded 31 as the owner and occupier of the mill and this remained the case through to 1921 when the Poor Rate Valuation List still records Metcalfe and Co Ltd as owners and occupiers.

The last of three cloth manufacturing mills to be built in Ossett Spa was Spa Mill, which was built circa 1854 for Priestley and Sussman. Unusually for Ossett, which was predominantly involved with the manufacture of woollen cloth, Spa Mill with the associated dyeworks was purpose-built for the manufacture of cotton cloth.

In May 1854, a local press report 32 tells of an inquest held at the nearby Fleece Inn after the unfortunate death of two workmen who had been killed during the construction of Spa Mill when an archway leading to the cellars had collapsed and crushed them to death. A verdict of accidental death was returned by the coroner.

At around the same time that Spa Mill was being built, James Marchent, iron founder and machine maker of Cole, Marchent & Co, Prospect Foundry, Bowling, Bradford was acquiring land on the south side of Ossett Spa. Marchent was to play an important role in the development of Ossett Spa in future years. Marchent was born in Leeds in 1794 and in 1857 dissolved his partnership in Cole, Marchent & Co, although the company continued to trade with the same name. Marchent began his acquisition of land and assets in the mid-1850s and had bought Spring End Mill, formerly Emmerson’s MIll (detailed above) in about 1855 as well as more land at Ossett Spa.

Almost immediately after Spa Mill and Dyehouse had been built, it was put up for sale by the owners and a notice appeared in the local press in January 1855: 33

“SPA MILLS AT OSSETT, NEAR WAKEFIELD – TO BE SOLD BY AUCTION, by Mr. Thornton at the house of Mr. John Berry, Hare and Hounds Inn, at Ossett, in the county of York on Thursday, February 1st 1855, at five o’clock in the evening.

All that newly erected MILL, situate and being at Ossett Common, in the county of York, with the Engine House, Boiler House, Warehouse, Counting House, Stables, Coach House, and spacious Yard within the premises. Also, that newly erected DYEHOUSE conveniently situated near the Mill. The whole of the premises with the open yard and vacant ground attached comprises one acre or thereabouts.The length of the Mill is 174ft and the breadth 110ft and the length of the dyehouse is 90ft and the breadth is 45ft. The whole of the premises have been recently erected in a most substantial manner for manufacturing or dyeing purposes; are well suited to worsted manufacturers; and no cost has been spared to make them convenient for the purposes required. The premises are at a convenient distance from the important manufacturing towns of Leeds, Dewsbury, Halifax, Huddersfield and Wakefield and are about one mile from the Railway Station at Horbury Bridge. The property is in the centre of a large coal district.

To view the premises, application may be made to Mr. Goldsmith, at the Spa Baths, near to the premises and further particulars, or to treat by private application may be made to Mr. Radcliffe, Architect, Huddersfield; the Auctioneer; or at the offices of Mr. Barker, Solicitor, Huddersfield, where a plan of the estate may be seen.

Huddersfield, January 9th 1855.”

James Marchent bought Spa Mill and the Dye House, which fronted Spa Street after this auction and between 1855 and 1860, Marchent had a huge property and land portfolio at Ossett Spa with his ownership of Spring End Mill, Spa Mill and the Dyeworks. What his intention was is not clear. He may have intended to run the mills as a going concern, alternatively, he may have been a speculator with an eye on a quick profit.

In the event, on the 8th December 1860, Marchent sold a large area of land at Ossett Spa, Spring End Mill, Spa Mill and the Dyehouse to the Lancashire and Yorkshire Cotton Manufacturing Company. It was noted in the conveyance11 that Spring End Mill had been in the tenure of Abraham Riley and David Lucas; the three-acre smallholding attached to Spring End Mill and fronting the Ossett to Horbury road was in the tenure of Reuben Dews (and previously Benjamin Fothergill).

The Lancashire and Yorkshire Cotton Manufacturing Company Ltd. made their intention clear in this 1860 public notice.34

“THE LANCASHIRE AND YORKSHIRE COTTON MANUFACTURING COMPANY – Limited, Capital £100,000, in 10,000 shares of £10 each. This company is formed to carry on the business of cotton spinning and manufacturing in all its departments.

The premises intended to be purchased by this Company are situate about half a mile from Horbury and about the same distance from Ossett in Yorkshire, have been built expressly for the spinning of cotton and compromise two new and one old mill, with three boilers, three engines, shafting warehouses, offices and every convenience. The whole of these premises compromise (including the site of the said buildings) about 5½ acres of land, full of excellent clay for the purpose of brick-making, free from any chief rent, land or other tax, except about £1 6s 8d per year, are within about a mile from Horbury Station, and situate in a neighbourhood where coals are cheap, and within a few hundred yards of these mills, and where labour is plentiful

The profits of the concern will, it is presumed, be on average of 25 to 30 per cent. The Executive Committee will compromise practical workmen, well versed in each department, so as to ensure the most economical working of the concern.

Applications for shares may be made to, and further information obtained from, Mr. William Hoyle, grocer, New Church-road; Mr. William Tagg, draper, Rochdale-road, Bacup; or of Mr. James Raby, inn-keeper, Peel’s Hotel, Bury, Lancashire; or of Mr. William Sykes, manufacturer, Church-street; Mr. Richard Greenwood, agent, Flatts, Dewsbury; Mrs. Richardson, inn-keeper, Horbury; or of Mr. James Stephenson, Temperance Hotel, Broad-street, Halifax, Yorkshire.”

However, it seems that despite a relatively prosperous period for some of Ossett’s mills and manufacturers in the 1860s, the cotton manufacturing venture at Ossett Spa was to fail. Trade Directories from the 1860s show that Edward Dews and Richard Holford were occupying Spa Mill as tenants by 1866, which suggests that the Lancashire & Yorkshire Cotton Manufacturing Co. Ltd only reigned for five or six years at Spa Mill and maybe a year longer at Spring End Mill before failing.

James Marchent died at his home in Bishopthorpe Terrace, York on August 30th 1863 aged 69, leaving a wife and four children. Marchent was an important player in the history of Ossett Spa and he clearly worked hard to acquire the mills and the land there over a five year period prior to 1860. His motive for this massive investment in Ossett isn’t clear. He had a successful seven-year business career with Cole, Marchent & Co., which he founded with John Cole in 1848. John Cole Sr. also died in (April) 1863, but the company continued as mill engine makers and general engineers at Prospect Foundry, Bowling, Bradford well into the 20th century.

In 1871, the Lancashire and Yorkshire Cotton Company sold the freehold of Spring End Mill (across the road from Spa Mill) together with 3 acres and 9 perches of land to Henry Oakes. Also, in 1871, after the failure of John Robinson, worsted manufacturer (who was renting part of Spa Mill as well as Spring End Mill), all the mill machinery associated with woollen worsted cloth manufacture at Spa Mill was offered for sale.35 There was also a second sale of Robinson’s mill machinery 36 , the latter occasion was the result of Robinson’s lease running out.

Edward Dews and Richard Holford purchased Spa Mill in 1872 and on the 22nd February 1872, the Lancashire and Yorkshire Cotton and MIning Co. Ltd. (and John Cole junior of Cole, Marchent and Co.) entered into a deed with Edward Dews and Holford whereby they acquired Ossett Spa Mill plus land and the buildings associated with the business. Dews’ business at Ossett Spa mill survived, but business partner Richard Holford is not mentioned in records and by 1880, Edward Dews alone was listed in the Ossett Valuation list as the mill’s owner. Similarly, the 1881 Kelly’s Directory records only Edward Dews, Yarn Manufacturer, Spa Mill, Ossett.

Dews was sub-letting some of the buildings at Spa Mill by 1875 to Thomas Robb, a flock manufacturer and Spa Mill suffered a very lucky escape in 1875:

Fire at Ossett 42

“On Monday afternoon a fire broke out in two sheds adjoining Mr. E. Dews’s Spa Mill, Ossett, and burnt for several hours before it was extinguished. The fire was caused, it is thought, by some hard substance accidentally being amongst some material which was in the act of being ground into flocks in a machine rented and worked by Mr. Thomas Robb, a Scotchman (sic), in one of the sheds. A pipe conveyed the ground flocks and dust into a wooden shed, and thus both sheds were set on fire. Had the wind not changed suddenly from west to east, the whole mill, a large one, would have been in flames in a short time. The buzzer of a neighbouring mill gave the alarm, and many persons assembled at the Spa Mill to render assistance. There was plenty of water at hand, and no fire-engines were sent for. The wood shed and its contents were completely destroyed. The brick shed was much injured, and altogether the damage reached £90 to £100. It is understood that Mr. Robb’s loss is covered by insurance.”

Dews suffered another setback in 1887 37 when his mill was deliberately put out of action for several days:

“OUTRAGE AT OSSETT – Early on Monday morning some evil-disposed person or persons tapped a large steam boiler at Mr. Edward Dews’s worsted spinning factory, The Spa, Ossett. About one a.m. the engine-man, who lives close by, got up and went outdoors in consequence of hearing a noise and found the boiler empty. A large key which had been used was also carried some distance away. The other boiler at the mill was not in use at the time, as it was about to be replaced by a new one, and the consequence of this malicious act is to stop the mill for a week.”

The 1889 Valuation List for Ossett Township records Edward Dews alone as the owner and occupier of Spa Woollen Mill, but also names Thomas Robb as the owner/occupier of adjacent rag grinding premises (most probably in wooden sheds in the grounds of Spa Mill) and Benjamin Crowther as the owner/occupier of the dyehouse immediately adjacent to Spa Mill. In 1889 38 it was reported that Edward Dews was about to hand over the business to his eldest son Ezra Dews, who was already by now managing the mill and living in the cottage which was on the Spa Mill site, set back a little from the Ossett to Horbury road.

Ezra Dews and subsequently another son, Frederick Dews became more involved in the family business at Spa Mill after the death of their father Edward Dews at the age of 68 years at his home, Whinfield House, Ossett Spa on the 26th June 1890. This was to be a bad decade for the Dews family and Ezra Dews died, aged 51, on the 1st of June 1896 after losing his wife Emma, aged 48 in 1892. Frederick Dews, who had some experience as a dyer now took over the running of Spa Mill after the death of his brother Ezra Dews. Sadly, Frederick Dews was to die at the early age of 44 in early 1898. Both Ezra and Frederick Dews had been owners of the nearby Fleece Inn and Frederick was the licensee as late as 1889 before they were involved in the management of Spa Mill.

The deaths, all within eight years of Edward Dews and his two sons Ezra and Frederick, was a substantial setback to the remaining members of the Dews family. In the event, none of the remaining members of the Dews family had the ability or perhaps the inclination to take on the running of Spa Mill. The youngest son Edward junior set up a drapers shop in Kirkgate, Wakefield with money given to him by his father, but had been declared bankrupt with liabilities of £500 in 1888 40 after just one year in business. Not surprisingly, the remaining members of the Dews family sought to sell Spa Mill with the manager’s house and garden plus about two acres of land in July 1900, 41 but bidding only reached £800 (about £45,000 in today’s prices) and consequently, the auctioneer was unable to achieve the reserve price.

Later in 1890, another auction was held on the instructions of Edward Dews’ executors to sell off the mill machinery at Spa Mill. Having failed to sell the mill earlier in the year as a going concern, the executors took the alternative of breaking it up to realise the value. The second auction was held on the 26th September 1900 and all of the mill machinery plus some 8,000 lbs of wool and waste were sold.

In October 1900, Spa mill now devoid of mill machinery was signed over to the Wakefield and Barnsley Union Bank by Harriet Dews and commercial traveller, Thomas Marshall. In 1901, the Ossett Valuation List records the bank as owners of an unoccupied worsted mill. Jessop Brook is shown as the owner/occupier of a shoddy mill, which was probably the adjacent dyehouse or sheds.

On the 17th March 1904, Spa Mill was sold to Elijah Tate, Theodore Medhurst and Annie Potts, all of Liverpool. Edward Simpson, soap manufacturer of Walton Hall, Wakefield provided the mortgage funds for the purchase. By 1905, Potts and Medhurst had sold their shares in Spa Mill to Elijah Tate, rag merchant with mortgage finance for the purchase this time provided by Mr. F.H. Oates. In 1910, the Inland Revenue Valuation records Jessop Brothers as occupiers of a mill and Eli Tate as the owner of a flock mill on Ossett Spa. Later in 1915, the Ossett Valuation List records Fawcett and Co. as occupiers of Spa Mill and Elijah Tate as the owner of “Extract Works.”

In 1916, Elijah Tate, formerly of Ossett and now of Harrogate, Gentleman sells his ownership of Spa Mill to Herbert Squires and Henry Arthur Fawcett “Wool Merino Extractors carrying on business at Ossett Spa in the style of Fawcett and Co.” The land and property sold by Tate to Fawcett and Co. comprised 1926 square yards of land with Spa Street frontage plus two cottages (formerly one larger house), outbuildings, conveniences, a warehouse and sheds. In addition, the sale included Spa Mill, a dwelling house and three cottages with outbuildings, conveniences and other buildings. The total area of land was about 2 acres and is shown on the drawing below. Jessop Brothers are shown as owner/occupiers of a similar facility elsewhere in Ossett Spa, most probably the dyehouse next to Spa Mill.

The last of three cloth manufacturing mills to be built in Ossett Spa was Spa Mill, which was built circa 1854 for Priestley and Sussman. Unusually for Ossett, which was predominantly involved with the manufacture of woollen cloth, Spa Mill with the associated dyeworks was purpose-built for the manufacture of cotton cloth.

In May 1854, a local press report 32 tells of an inquest held at the nearby Fleece Inn after the unfortunate death of two workmen who had been killed during the construction of Spa Mill when an archway leading to the cellars had collapsed and crushed them to death. A verdict of accidental death was returned by the coroner.

At around the same time that Spa Mill was being built, James Marchent, iron founder and machine maker of Cole, Marchent & Co, Prospect Foundry, Bowling, Bradford was acquiring land on the south side of Ossett Spa. Marchent was to play an important role in the development of Ossett Spa in future years. Marchent was born in Leeds in 1794 and in 1857 dissolved his partnership in Cole, Marchent & Co, although the company continued to trade with the same name. Marchent began his acquisition of land and assets in the mid-1850s and had bought Spring End Mill, formerly Emmerson’s MIll (detailed above) in about 1855 as well as more land at Ossett Spa.

Almost immediately after Spa Mill and Dyehouse had been built, it was put up for sale by the owners and a notice appeared in the local press in January 1855: 33

“SPA MILLS AT OSSETT, NEAR WAKEFIELD – TO BE SOLD BY AUCTION, by Mr. Thornton at the house of Mr. John Berry, Hare and Hounds Inn, at Ossett, in the county of York on Thursday, February 1st 1855, at five o’clock in the evening.

All that newly erected MILL, situate and being at Ossett Common, in the county of York, with the Engine House, Boiler House, Warehouse, Counting House, Stables, Coach House, and spacious Yard within the premises. Also, that newly erected DYEHOUSE conveniently situated near the Mill. The whole of the premises with the open yard and vacant ground attached comprises one acre or thereabouts.The length of the Mill is 174ft and the breadth 110ft and the length of the dyehouse is 90ft and the breadth is 45ft. The whole of the premises have been recently erected in a most substantial manner for manufacturing or dyeing purposes; are well suited to worsted manufacturers; and no cost has been spared to make them convenient for the purposes required. The premises are at a convenient distance from the important manufacturing towns of Leeds, Dewsbury, Halifax, Huddersfield and Wakefield and are about one mile from the Railway Station at Horbury Bridge. The property is in the centre of a large coal district.

To view the premises, application may be made to Mr. Goldsmith, at the Spa Baths, near to the premises and further particulars, or to treat by private application may be made to Mr. Radcliffe, Architect, Huddersfield; the Auctioneer; or at the offices of Mr. Barker, Solicitor, Huddersfield, where a plan of the estate may be seen.

Huddersfield, January 9th 1855.”

James Marchent bought Spa Mill and the Dye House, which fronted Spa Street after this auction and between 1855 and 1860, Marchent had a huge property and land portfolio at Ossett Spa with his ownership of Spring End Mill, Spa Mill and the Dyeworks. What his intention was is not clear. He may have intended to run the mills as a going concern, alternatively, he may have been a speculator with an eye on a quick profit.

In the event, on the 8th December 1860, Marchent sold a large area of land at Ossett Spa, Spring End Mill, Spa Mill and the Dyehouse to the Lancashire and Yorkshire Cotton Manufacturing Company. It was noted in the conveyance11 that Spring End Mill had been in the tenure of Abraham Riley and David Lucas; the three-acre smallholding attached to Spring End Mill and fronting the Ossett to Horbury road was in the tenure of Reuben Dews (and previously Benjamin Fothergill).

The Lancashire and Yorkshire Cotton Manufacturing Company Ltd. made their intention clear in this 1860 public notice.34

“THE LANCASHIRE AND YORKSHIRE COTTON MANUFACTURING COMPANY – Limited, Capital £100,000, in 10,000 shares of £10 each. This company is formed to carry on the business of cotton spinning and manufacturing in all its departments.

The premises intended to be purchased by this Company are situate about half a mile from Horbury and about the same distance from Ossett in Yorkshire, have been built expressly for the spinning of cotton and compromise two new and one old mill, with three boilers, three engines, shafting warehouses, offices and every convenience. The whole of these premises compromise (including the site of the said buildings) about 5½ acres of land, full of excellent clay for the purpose of brick-making, free from any chief rent, land or other tax, except about £1 6s 8d per year, are within about a mile from Horbury Station, and situate in a neighbourhood where coals are cheap, and within a few hundred yards of these mills, and where labour is plentiful

The profits of the concern will, it is presumed, be on average of 25 to 30 per cent. The Executive Committee will compromise practical workmen, well versed in each department, so as to ensure the most economical working of the concern.

Applications for shares may be made to, and further information obtained from, Mr. William Hoyle, grocer, New Church-road; Mr. William Tagg, draper, Rochdale-road, Bacup; or of Mr. James Raby, inn-keeper, Peel’s Hotel, Bury, Lancashire; or of Mr. William Sykes, manufacturer, Church-street; Mr. Richard Greenwood, agent, Flatts, Dewsbury; Mrs. Richardson, inn-keeper, Horbury; or of Mr. James Stephenson, Temperance Hotel, Broad-street, Halifax, Yorkshire.”

However, it seems that despite a relatively prosperous period for some of Ossett’s mills and manufacturers in the 1860s, the cotton manufacturing venture at Ossett Spa was to fail. Trade Directories from the 1860s show that Edward Dews and Richard Holford were occupying Spa Mill as tenants by 1866, which suggests that the Lancashire & Yorkshire Cotton Manufacturing Co. Ltd only reigned for five or six years at Spa Mill and maybe a year longer at Spring End Mill before failing.

James Marchent died at his home in Bishopthorpe Terrace, York on August 30th 1863 aged 69, leaving a wife and four children. Marchent was an important player in the history of Ossett Spa and he clearly worked hard to acquire the mills and the land there over a five year period prior to 1860. His motive for this massive investment in Ossett isn’t clear. He had a successful seven-year business career with Cole, Marchent & Co., which he founded with John Cole in 1848. John Cole Sr. also died in (April) 1863, but the company continued as mill engine makers and general engineers at Prospect Foundry, Bowling, Bradford well into the 20th century.

In 1871, the Lancashire and Yorkshire Cotton Company sold the freehold of Spring End Mill (across the road from Spa Mill) together with 3 acres and 9 perches of land to Henry Oakes. Also, in 1871, after the failure of John Robinson, worsted manufacturer (who was renting part of Spa Mill as well as Spring End Mill), all the mill machinery associated with woollen worsted cloth manufacture at Spa Mill was offered for sale.35 There was also a second sale of Robinson’s mill machinery 36 , the latter occasion was the result of Robinson’s lease running out.

Edward Dews and Richard Holford purchased Spa Mill in 1872 and on the 22nd February 1872, the Lancashire and Yorkshire Cotton and MIning Co. Ltd. (and John Cole junior of Cole, Marchent and Co.) entered into a deed with Edward Dews and Holford whereby they acquired Ossett Spa Mill plus land and the buildings associated with the business. Dews’ business at Ossett Spa mill survived, but business partner Richard Holford is not mentioned in records and by 1880, Edward Dews alone was listed in the Ossett Valuation list as the mill’s owner. Similarly, the 1881 Kelly’s Directory records only Edward Dews, Yarn Manufacturer, Spa Mill, Ossett.

Dews was sub-letting some of the buildings at Spa Mill by 1875 to Thomas Robb, a flock manufacturer and Spa Mill suffered a very lucky escape in 1875:

Fire at Ossett 42

“On Monday afternoon a fire broke out in two sheds adjoining Mr. E. Dews’s Spa Mill, Ossett, and burnt for several hours before it was extinguished. The fire was caused, it is thought, by some hard substance accidentally being amongst some material which was in the act of being ground into flocks in a machine rented and worked by Mr. Thomas Robb, a Scotchman (sic), in one of the sheds. A pipe conveyed the ground flocks and dust into a wooden shed, and thus both sheds were set on fire. Had the wind not changed suddenly from west to east, the whole mill, a large one, would have been in flames in a short time. The buzzer of a neighbouring mill gave the alarm, and many persons assembled at the Spa Mill to render assistance. There was plenty of water at hand, and no fire-engines were sent for. The wood shed and its contents were completely destroyed. The brick shed was much injured, and altogether the damage reached £90 to £100. It is understood that Mr. Robb’s loss is covered by insurance.”

Dews suffered another setback in 1887 37 when his mill was deliberately put out of action for several days:

“OUTRAGE AT OSSETT – Early on Monday morning some evil-disposed person or persons tapped a large steam boiler at Mr. Edward Dews’s worsted spinning factory, The Spa, Ossett. About one a.m. the engine-man, who lives close by, got up and went outdoors in consequence of hearing a noise and found the boiler empty. A large key which had been used was also carried some distance away. The other boiler at the mill was not in use at the time, as it was about to be replaced by a new one, and the consequence of this malicious act is to stop the mill for a week.”

The 1889 Valuation List for Ossett Township records Edward Dews alone as the owner and occupier of Spa Woollen Mill, but also names Thomas Robb as the owner/occupier of adjacent rag grinding premises (most probably in wooden sheds in the grounds of Spa Mill) and Benjamin Crowther as the owner/occupier of the dyehouse immediately adjacent to Spa Mill. In 1889 38 it was reported that Edward Dews was about to hand over the business to his eldest son Ezra Dews, who was already by now managing the mill and living in the cottage which was on the Spa Mill site, set back a little from the Ossett to Horbury road.

Ezra Dews and subsequently another son, Frederick Dews became more involved in the family business at Spa Mill after the death of their father Edward Dews at the age of 68 years at his home, Whinfield House, Ossett Spa on the 26th June 1890. This was to be a bad decade for the Dews family and Ezra Dews died, aged 51, on the 1st of June 1896 after losing his wife Emma, aged 48 in 1892. Frederick Dews, who had some experience as a dyer now took over the running of Spa Mill after the death of his brother Ezra Dews. Sadly, Frederick Dews was to die at the early age of 44 in early 1898. Both Ezra and Frederick Dews had been owners of the nearby Fleece Inn and Frederick was the licensee as late as 1889 before they were involved in the management of Spa Mill.

The deaths, all within eight years of Edward Dews and his two sons Ezra and Frederick, was a substantial setback to the remaining members of the Dews family. In the event, none of the remaining members of the Dews family had the ability or perhaps the inclination to take on the running of Spa Mill. The youngest son Edward junior set up a drapers shop in Kirkgate, Wakefield with money given to him by his father, but had been declared bankrupt with liabilities of £500 in 1888 40 after just one year in business. Not surprisingly, the remaining members of the Dews family sought to sell Spa Mill with the manager’s house and garden plus about two acres of land in July 1900, 41 but bidding only reached £800 (about £45,000 in today’s prices) and consequently, the auctioneer was unable to achieve the reserve price.

Later in 1890, another auction was held on the instructions of Edward Dews’ executors to sell off the mill machinery at Spa Mill. Having failed to sell the mill earlier in the year as a going concern, the executors took the alternative of breaking it up to realise the value. The second auction was held on the 26th September 1900 and all of the mill machinery plus some 8,000 lbs of wool and waste were sold.

In October 1900, Spa mill now devoid of mill machinery was signed over to the Wakefield and Barnsley Union Bank by Harriet Dews and commercial traveller, Thomas Marshall. In 1901, the Ossett Valuation List records the bank as owners of an unoccupied worsted mill. Jessop Brook is shown as the owner/occupier of a shoddy mill, which was probably the adjacent dyehouse or sheds.

On the 17th March 1904, Spa Mill was sold to Elijah Tate, Theodore Medhurst and Annie Potts, all of Liverpool. Edward Simpson, soap manufacturer of Walton Hall, Wakefield provided the mortgage funds for the purchase. By 1905, Potts and Medhurst had sold their shares in Spa Mill to Elijah Tate, rag merchant with mortgage finance for the purchase this time provided by Mr. F.H. Oates. In 1910, the Inland Revenue Valuation records Jessop Brothers as occupiers of a mill and Eli Tate as the owner of a flock mill on Ossett Spa. Later in 1915, the Ossett Valuation List records Fawcett and Co. as occupiers of Spa Mill and Elijah Tate as the owner of “Extract Works.”

In 1916, Elijah Tate, formerly of Ossett and now of Harrogate, Gentleman sells his ownership of Spa Mill to Herbert Squires and Henry Arthur Fawcett “Wool Merino Extractors carrying on business at Ossett Spa in the style of Fawcett and Co.” The land and property sold by Tate to Fawcett and Co. comprised 1926 square yards of land with Spa Street frontage plus two cottages (formerly one larger house), outbuildings, conveniences, a warehouse and sheds. In addition, the sale included Spa Mill, a dwelling house and three cottages with outbuildings, conveniences and other buildings. The total area of land was about 2 acres and is shown on the drawing below. Jessop Brothers are shown as owner/occupiers of a similar facility elsewhere in Ossett Spa, most probably the dyehouse next to Spa Mill.

By October 1929, Fawcett and Co. Ltd, who had incorporated in April 1921 as a limited company, were in severe financial difficulties. This was as a result of the Great Depression of 1929-32, which broke out at a time when the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was still far from having recovered from the effects of the First World War. The firm defaulted on the payment of a debenture and were effectively bankrupt and so the banks foreclosed and called in the Official Receiver in the form of one Gordon Ball who put Spa Mill and the associated buildings and land up for sale in 1930. The sale was split into Lots 1, 2 and 3 as can be seen from the drawing above. In the event all three lots were sold for just £600, which was £200 less than the best offer made and rejected in 1904 and equivalent to about £20,000 today. The buyer was fellmonger Joseph Illingworth of Springbank House, Ossett who would be associated for this part of Ossett Spa for the next 70 years or so.

Left: The Bungalow on Spa Lane referenced in the sale drawing above.

Left: The Bungalow on Spa Lane referenced in the sale drawing above.

Illingworth immediately sold the bungalow (shown also on the top left of the drawing above ) and 1,250 square yards of land to Harry Smith, who had been renting the bungalow previously. The sale price of the bungalow and land was just £280 so in less than a year, Joseph Illingworth had already recouped almost half of the purchase price of the Spa Mill estate. The bungalow, now a two-storey house is still standing in 2010 and was recently offered for sale at £425,000. IN August 2010, the house (currently owned by Fred Burrows) was subject to a police investigation when it was discovered that the house, on the market for sale, but being rented out pending a sale, was being used by Vietnamese tenants illegally for the growing of cannabis.

In 1933, Spa Mill was disused as can be seen on the 1933 O.S. map of Ossett Spa Mills further up this page and in 1949, Frank Chambler and ice cream merchant, who lived on Spa Street, bought Spa Mill for £200. Between 1951 and 1953, Chambler sold the mill and land to Fred Douglas, a miner, also of Spa Street. It is likely that Chambler and Douglas had already demolished Spa Mill during the period of their respective ownerships. Finally, in 1967, John and Joan Miriam Myers buy the Mill site and move from Royds Villas in Gawthorpe to live in one of the cottages on Spa Lane. John Myers is currently (2010) living in a detached bungalow off Spa Lane, built circa 1987, on the site of the former mill.

The 18th Century “Engine” and Windmill at Ossett Spa

Alongside the description “Engine”, a mysterious symbol that looks like a windmill is shown in the fields of South Ossett on Jeffreys 1775 map, which is one of the earliest known maps of Ossett. Was there a windmill at Ossett Spa in the late 18th century or is a further clue given in the 1795 Manor Map of Ossett, which shows a structure in the same area named “Roundhouse”? And what was the “Engine?” A few years later than the Jeffreys map, the 1790 Manor of Wakefield Estate Map similarly shows “Round House” and “Steam Engine” in different locations all in the vicinity of Ossett Spa.

The Jeffreys map and the Manor Estate map reference to “engine” or “steam engine” can be attributed to the engine at Spring End Mill which was known to have stood there about the time of Jeffreys’ survey. The nature of the Round House or Windmill is more speculative.

Tower windmills are certainly round, but in this case, it is unlikely that it was a windmill, but in fact a pumping engine on the site of an 18th century coal mine that was owned then by the Naylor family. It is likely that this was actually on the site of Manor Colliery, which was owned at one stage by Terry, Greaves and Co, of Roundwood Colliery fame and then in December 1857 by John Mitchell, who leased the area known as “Drain Close” from the Ingham family in 1843, at the time of the Tithe Award. Drain Close is adjacent to the field named Whynn Ginn in the 1843 Tithe Award in which the Round House appears to have stood.

The 1890 O.S. Map for Ossett shows a circular structure in a field between Spa Lane and Manor Road. This field is marked on the 1842 Tithe Award Map as “Whinn Gynn” and some Ossett historians18 believe this can be interpreted as “Windmill Engine”. In 1843 this field was rented by John Wilby from The Earl of Cardigan. Wilby’s son was Joshua Wilby who was a farmer and a collier and late in his life he became owner of Runtlings Colliery.

The remnants of the roundhouse structure may well have still been there in 1890, alternatively, the feature shown on the map could be a pond caused by the land sinking in the area of the now filled-in coal mine shaft.

The site of the roundhouse, in the fields between Spa Lane and Manor Road is in a distinct dip in the surrounding land and would have been a very poor choice for the site of a windmill. In the early 18th century, a man called Thomas Newcomen (1663-1729) developed a steam-powered pumping engine called a beam engine, which was widely used in coal mines for pumping out water from the workings. In 1712, Thomas Newcomen together with John Calley built their first engine on top of a water filled mine shaft and used it to pump water out of the mine. This new development allowed the coal masters to develop deeper mines, which gave access to the rich coal seams, which abound in this part of Ossett. Intriguingly, some of Newcomen’s beam engines were housed in circular buildings made from stone or brick. There was plenty of water and coal on site at Ossett Spa to power the steam engine and one plausible explanation for the structure shown on the early maps is that it was a Newcomen beam engine or something similar. My thanks to Neville Ashby for suggesting that Roundhouse may have been the housing for a Newcomen steam-powered beam engine. It is my view that the “Roundhouse” refers to the round building that used to house the early water pumping engine at Naylor’s Pit.

The site of the roundhouse, in the fields between Spa Lane and Manor Road is in a distinct dip in the surrounding land and would have been a very poor choice for the site of a windmill. In the early 18th century, a man called Thomas Newcomen (1663-1729) developed a steam-powered pumping engine called a beam engine, which was widely used in coal mines for pumping out water from the workings. In 1712, Thomas Newcomen together with John Calley built their first engine on top of a water filled mine shaft and used it to pump water out of the mine. This new development allowed the coal masters to develop deeper mines, which gave access to the rich coal seams, which abound in this part of Ossett. Intriguingly, some of Newcomen’s beam engines were housed in circular buildings made from stone or brick. There was plenty of water and coal on site at Ossett Spa to power the steam engine and one plausible explanation for the structure shown on the early maps is that it was a Newcomen beam engine or something similar. My thanks to Neville Ashby for suggesting that Roundhouse may have been the housing for a Newcomen steam-powered beam engine. It is my view that the “Roundhouse” refers to the round building that used to house the early water pumping engine at Naylor’s Pit.

Left: A picture of a Newcomen Beam Engine in operation during the mid 19th century. This is not the one at Ossett Spa, but it gives an indication of what the structure might have looked like. Some of the larger Newcomen engines had a square housing, which looked more like a house. Although the engines were not particularly efficient, they could pump water out of coal mines at least 200ft deep and many hundreds were built long after Thomas Newcomen had died.

In July, 2010, Neville Ashby and Alan Howe did some further surveying work on the approximate site of the roundhouse with a metal detector after first getting permission from the landowner at Brookes Farm, Horbury Road. There is a land drain running through the site at a field boundary that would have been built to take away the pumped out water from Naylor’s Pit. Although there was much evidence of coal fragments on the site, there was little evidence of stone or brick, which must have been used to build the structure housing the steam chamber and beam engine. However, it is likely that the old pit shaft was filled in with the building rubble when the roundhouse was demolished.

Some bits of wrought iron metal machinery of indeterminate age were found with the help of the metal detector as well as some early 19th century copper-alloy buttons. There was certainly some kind of engine on this site, but as yet no firm conclusions can be made. There may yet be some record of early land sales and wayleaves agreements granting access for the mining of coal under the land in the Wakefield Archive, but as yet this has not been researched.

References: