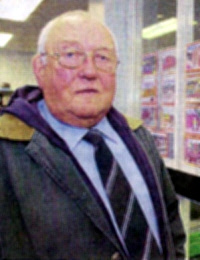

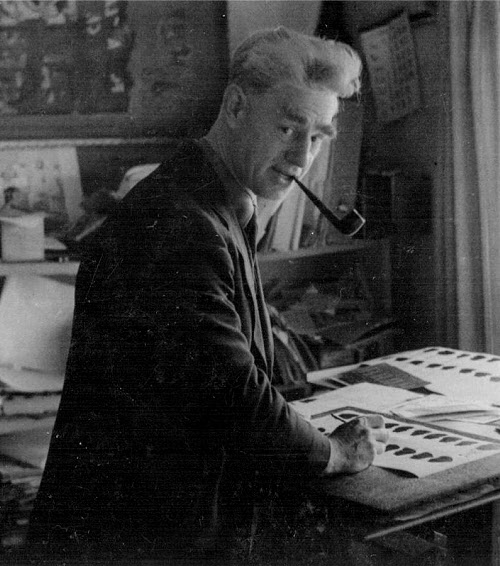

Before his death in May, Douglas Brammer ensured that the once-thriving community of Flushdyke would be remembered well into the future

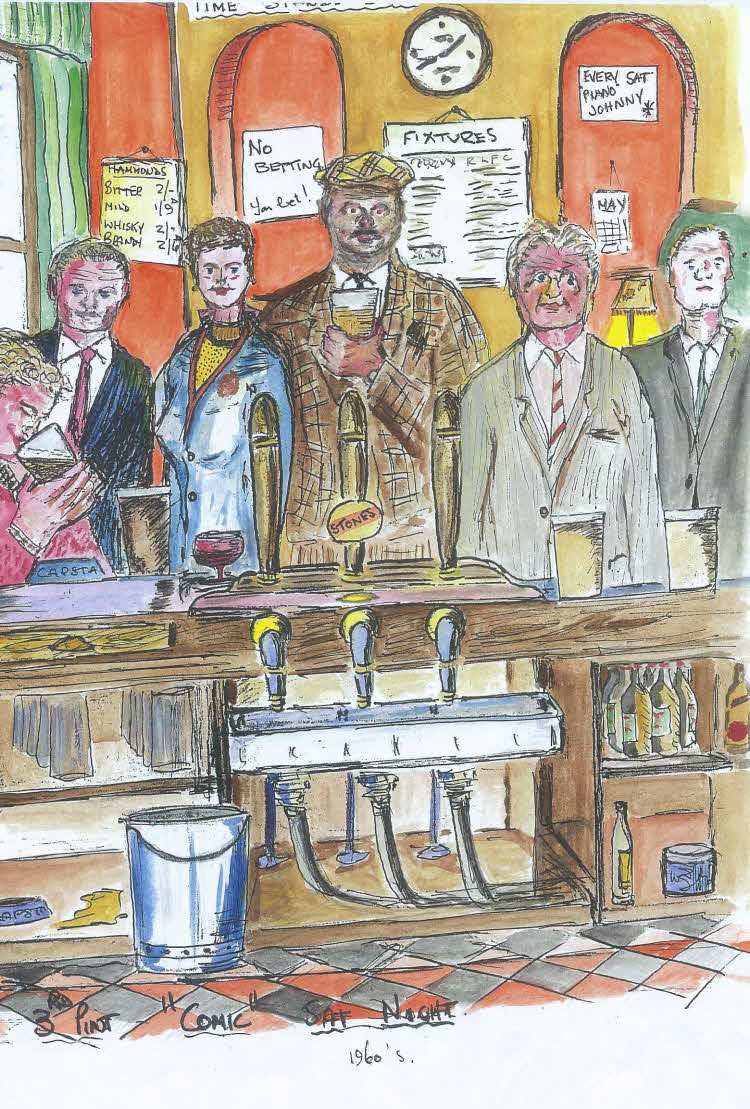

Douglas Morton Brammer left behind a remarkable legacy. Using his photographic memory and artistic skills, he created a series of sketches capturing the spirit of a long- gone community.

When Douglas was born in Flushdyke, in 1937, it was a bustling self-contained suburb of Ossett, with churches, chapels, shops, pubs and a school. But, by the 1970s, most of it had been subsumed into a sprawling industrial estate.

Today, few pictures remain of the village, but Douglas’ ninety or so sketches ensure it will not be forgotten. And, in September, they will be published in a book, with all proceeds going to a worthwhile cause.

“My brother drew these sketches primarily for his own purposes,” said his sister, Margaret Wilby. “He was a very sociable person but modest when it came to his own abilities. The sketches of Flushdyke and later of Ossett were drawn over many years whenever some- thing triggered a memory and he wanted to recreate the moment visually as well as in his mind.

“Having shared many of these experiences with him over our early lives, I was very interested and asked him for copies of his work for myself. I put these away and did not share them until about ten years later when I showed them to my son and his wife. Their reactions gave me the confidence to then show them to local historian Alan Howe, with whom I had become acquainted through our interest in local history.

“He put a wider value on the images as someone who knew from maps and a few photographs what had once existed but was now long-gone. The rest is history, as they say, and a lot of hard work by Alan is bringing them to a wider audience and hopefully giving them a longer life than they might have had.”

Alan described Douglas as “a remark- able man” and said his sketches were of “immense historical importance”. “His photographic memory, sense of community and artistic skills have captured the history of a part of Ossett, Flushdyke, that is long-gone,” he added. “His life and his love of his community are reflected in every single one of the sketches he gifted to the community.

“In his sketches of Flushdyke, in particular, he has captured a world swept away by industrialisation in the early to mid 1970s. Not just the buildings, many of which are now no more, but also the people, the character, the spirit, the very being of that community. They are unique.

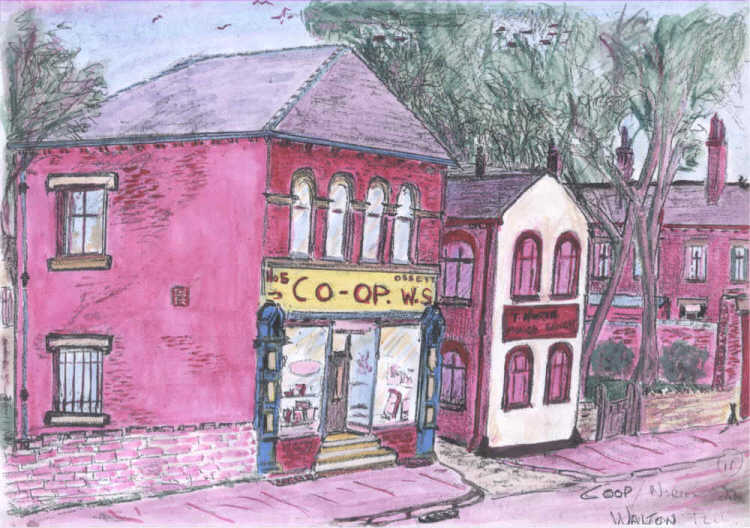

“These sketches are no copy of photographs. They are from his phenomenal memory, from his mind and from his heart. They are a pictorial biography of Douglas Brammer’s life.” Born just before the Second World War, Douglas and his sister, Margaret, attended Flushdyke Council School where their mother, Eleanor, was a highly respected dinner lady. Their father, Sydney – who had been one of the first pupils at the school when it opened in 1912 – was away, serving with the Army in East Africa. In 1946, he resumed the managership of the local Co-operative store.

Work, school and places to play were all within walking distance of their home. “Flushdyke was a community, even though it didn’t have a centre. It was divided by the A638 road – an old Roman route. Social life revolved around the school, Bethel Chapel, St Oswald’s Mission and the Co-op,” recalled Margaret. “It was a happy place to live and I have many good memories. Everyone watched out for each other.”

At eleven, Douglas went to Ossett Grammar School. One year, for his art exam, he was told to paint a picture of a cricket match, but his portrayal was not of a conventional scene. It depicted urchins playing cricket in a back alley, with the wicket chalked on a wall. “My brother saw interest and value in less conventional things,” said Margaret. “He never romanticised anything and had no pretensions.”

After leaving school, he worked in the engineering industry and was a union convenor. He completed a Certificate in Industrial Relations at Leeds University and then studied for a Diploma in Social Work at Huddersfield University, later becoming a probation officer and social worker. “He always saw the worth in people,” said Margaret. “He did not do things for rewards. He was a very modest person, who was sensitive and observant. He cared about people.”

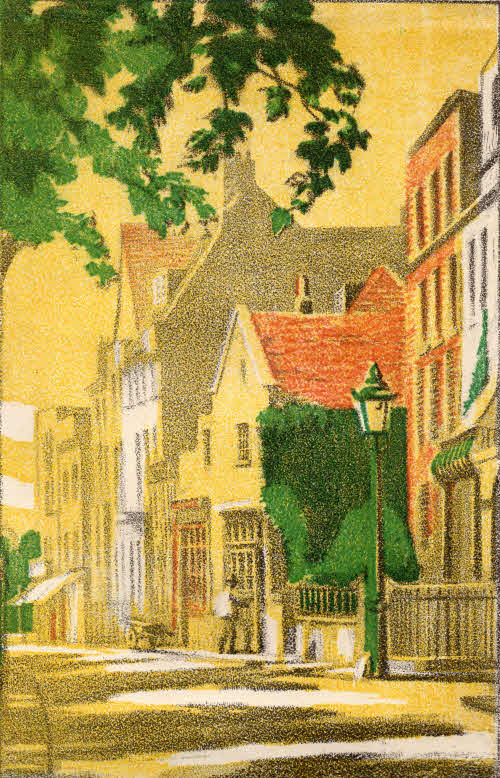

Flushdyke Co-op where Douglas’ father was manager for ten years

The inspiration for his sketches was a pub conversation with his friend, Don Boocock, in which they recalled how, in the 1960s and 1970s, the village had been decimated. The close proximity of the M1 had made Flushdyke a prime location for development. The community was soon overwhelmed with factories and traffic. Homes were seized, demolished and replaced with huge steel buildings and warehouses.

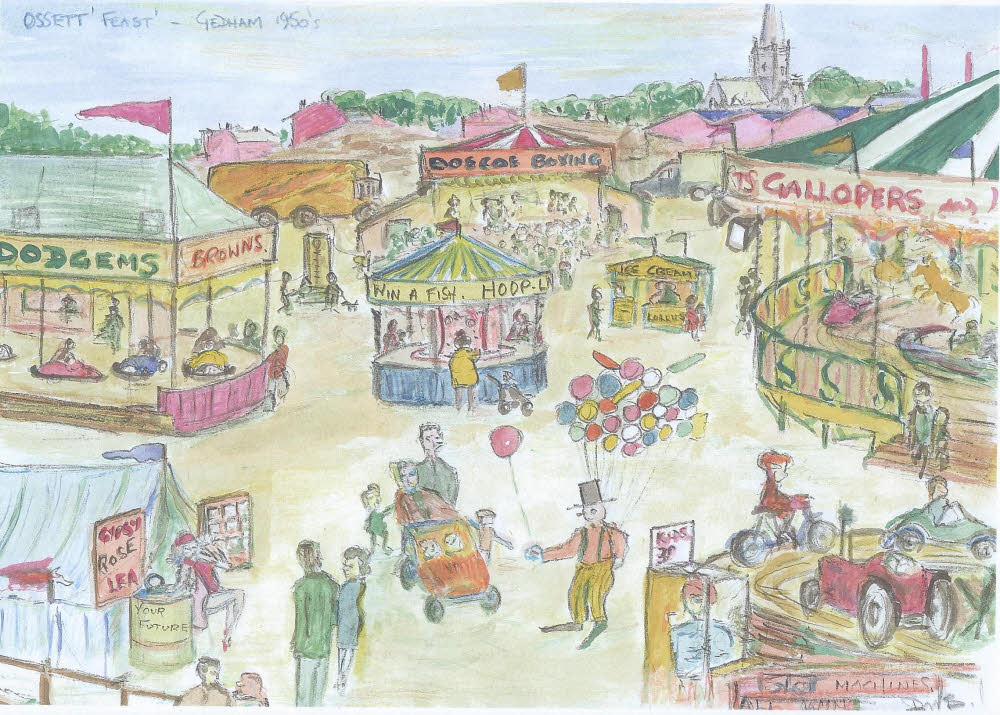

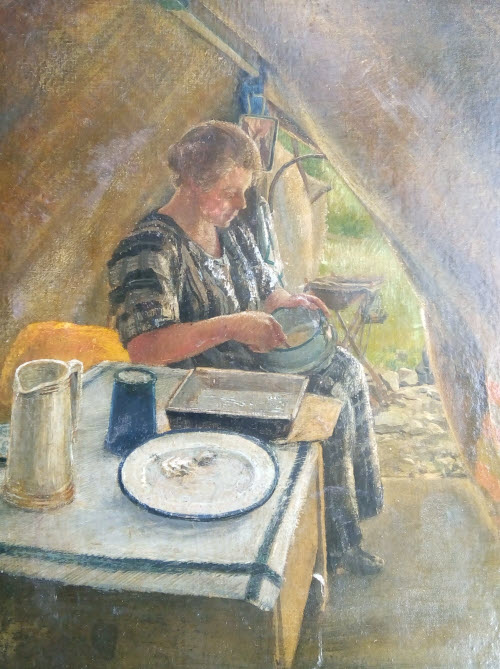

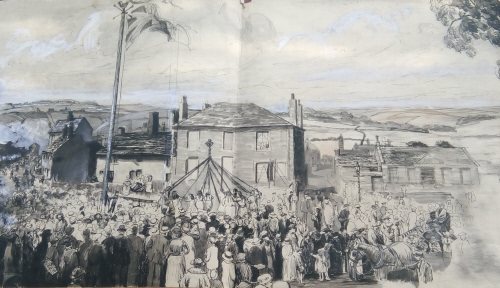

Ossett Feast

Other friends in the pub became interested in their recollections and wanted to know where these places had been. It was then Douglas realised that there was little photographic record of Flushdyke from before it was swept away by the industrialisation.

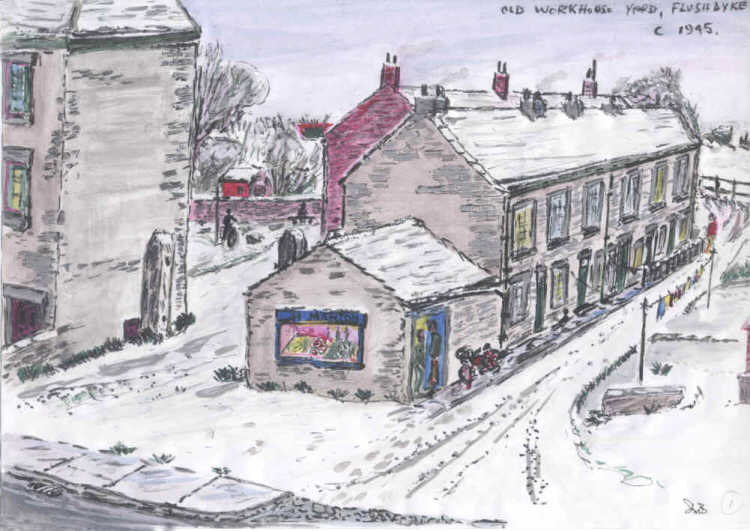

Later that week he drew his first sketch. It was of Workhouse Yard. And, like his subsequent sketches, it showed the essence and the spirit of the area as it was in the 1940s and 1950s. Another of his sketches was of Longlands House, which sat in its own grounds, where Douglas delivered newspapers as a thirteen-year-old. Sixty years later, he drew it from memory as the house was one of those demolished in the 1970s.

“A photograph subsequently emerged of the house, which showed the amazing accuracy of Douglas’ drawing,” said Margaret. “It gives credence to his other works. The sketches provide a walk through our early life.”

Drinking mates at The Commercial Inn, also known as The Comic

Douglas is also credited with helping Drinking mates at The Commercial Inn, also known as The Comic to save Flushdyke School – another of the places he drew in his sketches. Serving as chairman of the govern- ors, he led opposition to Wakefield Council’s proposal to close the school in the 1990s. The authority was concerned that it did not have its own catchment area, but Douglas argued that instead of closing an excellent school and transporting children from Flushdyke to other areas, children from surrounding areas should be brought in so they too could benefit from a smaller, quieter, more attentive environment. The closure plan was abandoned and, as a result, Flushdyke School continues to serve local children today. Douglas’ artistic legacy also lives on – not only through his sketches, but also the imminent publication of a book containing his work. Ever the modest man, Douglas was hesitant in the beginning but became gradually accepting of the idea. Sadly he passed away before the project could come to fruition, but family and friends pressed on and, later this month, Sketches of Past Times Flushdyke and Ossett, will be published. It contains almost 100 of Douglas’s’ sketches, accompanied by maps showing their location and a social and historical narrative. The book will be available from Ossett Library in the town hall. Meanwhile, you can view the entire Brammer collection here

Miss Hannah Pickard (1838-1891) was a member of a prominent Ossett textile family and lived her later life at “Green Mount”, at the junction of Southdale Road and Ossett Green. Ossett grocer and draper, George Pickard (born 9th April 1798, a Quaker birth) married Hannah Mitchell (born 1805) in 1824 and they had four children, two boys and two girls: Sarah, born in 1826; David born in 1830, Andrew born in 1835 and Hannah born in 1838. The family lived in a cottage, said to be where “Green Mount” would later be built. The Pickard family had existed in Ossett for generations.

When Miss Hannah Pickard passed away at her home, Green Mount, Ossett, on 29th June 1891, she left behind an estate worth in excess of £174,486. Hannah had inherited her fortune from her father, George Pickard, and her brothers David and Andrew. Having only one living heir, her nephew George (who died the following year aged 21), she set about making sure her wealth would be distributed near and far for the good of the poor and needy. The “Ossett Observer”, dated Saturday, 11th July 1891, published a list of bequests totalling £34,950 contained in her will.

Institutions from Leeds to London were named but her home town was certainly not forgotten. Her legacy to Ossett included:

It was this last bequest which was to provide the most visual reminder of Hannah.

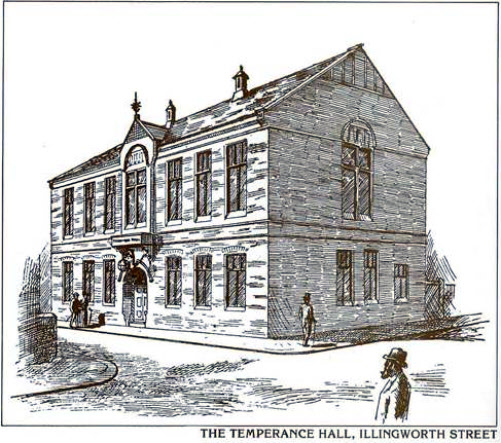

The Corporation chose a design by local architect Mr W. A. Kendall and a team of contractors including Messrs R. Tolson and Sons – masons, Mr P Wills – sculptor (who also supplied the granite), Mr J W Appleyard – sculptor, Leeds (who carved the figures near the base), and Messrs J Snowden & Son – plumbers, who carried out the work.

Left: The Pickard Fountain, Ossett circa 1900.

The “Ossett Observer” dated Saturday 28th October 1893 described the fountain and the opening ceremony:

“It occupies a conspicuous position near the centre of the Market Place, and is a very ornamental structure. Standing on a circular base of Aberdeen granite, the fountain itself is mainly of Bolton Wood stone, enriched with figures and other carving; but the shaft and massive bowl are of polished Peterhead granite. On the shaft is carved a lion (which is the crest of the Pickard family), the borough arms, and the following inscription:”

‘”This fountain is the gift of the late Miss Hannah Pickard, of this town, to the Corporation of Ossett for the benefit of the inhabitants and was erected in 1893. W A Kendall, architect.” The whole is about 15 feet high, and four gas lamps are attached to the upper portion. The water flows into the bowl already mentioned, and from thence into four drinking troughs for cattle and as many smaller ones for dogs.”‘

The opening ceremony took place on Saturday, 21st October 1893. The Mayor, Cllr. F. L. Fothergill was the guest of honour. The “Ossett Observer” set the scene:

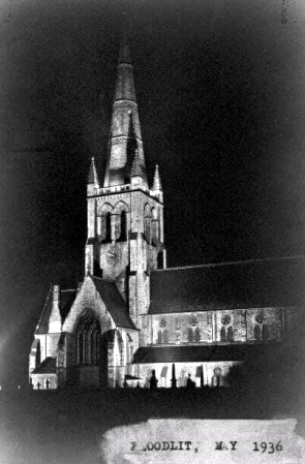

“The members and officials of the Corporation, representatives of the Chamber of Commerce, Tradesmans’ Association, and Cooperative Society, with other gentlemen, met at the Temperance Hall, and, headed by the Borough Band, walked in procession to the fountain, which was surrounded by a crowd of two or three thousand spectators.

The Town Clerk (Mr Willie Brook) read two letters, which had been addressed by Mr J J Jackson, one of Miss Pickard’s executors, to the architect. The first stated that the executors were unable to attend, and suggested that the Mayor should undertake the opening. The second, which was dated 8th September, intimated that, owing to a sharp attack of bronchitis, there was no chance of the writer’s attending the ceremony, but trusted that everything would pass off well and that the good folks of Ossett would be pleased with the results of Mr Kendall’s labours. Mr Brook also read an extract from Miss Pickard’s will.

The band then played “Auld lang syne.”

The Mayor, in official robe and chain, informed those gathered that:

“Although he had not known the late Miss Pickard personally, he was informed that she was a very benevolent lady, always good to the poor, and they had some proof in the fact that she had bequeathed five sums of £1,000 each for the relief of the poor in her native town, and also two sums of £2,100 each for the foundation of scholarships. He trusted that the fountain would be kept in order and long remain an ornament to the town and not be allowed to become a nuisance as some people rather feared might be the case. The water was then turned on, and his worship filled one of the drinking cups and drank prosperity to the borough. His example was followed by several others.”

Other Councillors also spoke highly of Hannah and her generosity. Alderman Clay said:

“…the donor of this chaste and beautiful fountain was a lady of very kindly and benevolent disposition, as shown by the large sums which she had bequeathed to charities, not merely in Ossett, but in other parts of the country. Her kindness in this instance had been shown by providing one of the essentials of life for man and beast. He hoped that the fountain would stand as a memorial of her goodness and generosity for many generations to come, and that the inhabitants generally would endeavour to preserve it in all its beauty. He trusted also that other ladies and gentlemen who had the means would endeavour to beautify their native town.”

Alderman Wilson moved a vote of thanks to the Mayor and also spoke in complimentary terms of the design and construction of the fountain. Alderman Mitchell seconded the motion and added that:

“…other wealthy persons in Ossett had died, and their money had gone out of the town; but Miss Pickard had bequeathed large sums for the benefit of the inhabitants. The late Mr Gunson, of Scarborough, an Ossett gentleman, had also made provision for the erection of some almshouses. He hoped that others would follow suit in leaving a portion of their wealth to the town in which it had been made. The resolution was carried by acclamation.”

The Mayor replied that it had been a pleasure to him to perform the task and that he considered the fountain a credit to the architect and contractors, indeed everyone who had had a hand in its construction. Councillor J. W. Smith motioned and Mr W. Patterson, president of the Chamber of Commerce seconded a vote of thanks to the architect and contractors. Mr. Kendall briefly replied on behalf of the contractors and himself.

“…the old stocks used to stand on the site of the fountain, but he was pleased to see the old bogey replaced by something more beautiful to look upon and useful to both man and beast. A nobler woman than Miss Pickard had never lived, and had she lived longer she would have been a yet greater blessing to the poor of the borough. He hoped that her example might do something to spur others who were quite as able but not so willing (a laugh).

The band then played the National Anthem and the procession returned to the Temperance Hall, where nearly 30 gentlemen were entertained at tea by the Mayor. At the conclusion of the repast, several complimentary speeches were made, and thanks accorded to his worship.”

It must have been quite a spectacle to see. Unfortunately, the sentiments of the Mayor and Alderman Clay were to be fairly short lived as, by the early 1950s, the fountain no longer had its ornate lamps and the water troughs had been converted into flower beds. Sadly, in the late 1950s the decision was made to remove the fountain from the town centre. It was eventually relocated to Green Park where it remained until 2007. After suffering vandalism and neglect, a decision was made by Wakefield District Council to scrap the fountain. Most of it was given to a landscape gardener, Adrian Richardson, who took it to his farm in Sharlston.

Helen Bickerdike, May 2016

In the cold winter months of 1846, a baby son Eli was born to a hand-loom weaver, Mathew Henry Townend and his new wife Hannah who lived in a small cottage in old Church Street, near the centre of the town of Ossett. Eli Townend was baptised at the Old Church in Ossett on the 15th March 1846. 23 year-old Matthew Townend had married Hannah Harrop at Dewsbury in the summer of 1845. Eli was to be the first of their family of seven children.1

In the cold winter months of 1846, a baby son Eli was born to a hand-loom weaver, Mathew Henry Townend and his new wife Hannah who lived in a small cottage in old Church Street, near the centre of the town of Ossett. Eli Townend was baptised at the Old Church in Ossett on the 15th March 1846. 23 year-old Matthew Townend had married Hannah Harrop at Dewsbury in the summer of 1845. Eli was to be the first of their family of seven children.1

Sadly, Eli Townend had a bad start to life when he was born with a serious impediment to his eyesight, which made it impossible for him to learn how to read and write. The Townend family were desperately poor with many mouths to feed and young Eli never attended school. This was before the days of compulsory education and his parents couldn’t afford the one penny a day to send him to one of the schools in the town.

Eli Townend later recalled his childhood days in one of his speeches:2

“This was when the families of working men rarely saw new milk, never saw butter and seldom touched meat and when the head of the family earned 12 shillings a week for nine months and nothing for the remaining months.”

Eli’s father Matthew died in 1870 at the early age of 48 and Matthew’s wife Hannah also died some three years later aged 49; their lives probably shortened by poor diet, disease and the primitive health care of the times. From this uncompromising start Eli Townend was destined to become one of Ossett’s most notable and successful citizens. A noted philanthropist and people’s champion, Townend became a wealthy factory owner who devoted over forty years of his life to serving the public of Ossett and was fondly remembered when he died in July 1910.

When Eli was 8 or 9 years of age, and to supplement their meagre income, his parents became caretakers of the “Saloon” on Bank Street, which was not a drinking establishment modelled on those in the American wild west, but was in fact a Temperance club, more often referred to as “t’owd saloon” by the Ossett locals.3 In the 19th century, Ossett people had a strong tradition of support for the Temperance movement, where the drinking of any alcohol was eschewed in favour of teetotalism. The “Saloon” was open to all classes of people, but was patronised largely by working men who went there in the evenings to play board games such as whist, chess and draughts; to read the daily newspapers and to discuss the topics of the day.

It was here that young Eli developed his remarkable mental faculties by listening to the conversations of the patrons, analysing what was being discussed and eventually storing a huge fund of knowledge on many varied subjects in his receptive young mind. Eli Townend would constantly add to this knowledge and use it to very good effect in later life.

SUCCESS IN BUSINESS

Eli Townend’s rise in the world was rapid, but his first few jobs were menial. As a lad, Townend started work at an early age, doing any available job that was suitable for someone with very weak eyesight. When the “Ossett Observer” was first published in 1864 by Mr. T.R. Beckett, it was 15 year-old Eli Townend who operated the handle on the primitive printing press.

He continued this task for on a weekly basis for for some time afterwards. Townend’s connection with the “Ossett Observer” continued in other ways long after that employment ceased and it was he that that laid the foundation stone of the Borough Printing Works, the opening ceremony taking place at six o’clock in the morning. In fact, for 25 years, Townend saved every issue of the “Ossett Observer” and subsequently presented the bound volumes to Ossett Library.

He continued this task for on a weekly basis for for some time afterwards. Townend’s connection with the “Ossett Observer” continued in other ways long after that employment ceased and it was he that that laid the foundation stone of the Borough Printing Works, the opening ceremony taking place at six o’clock in the morning. In fact, for 25 years, Townend saved every issue of the “Ossett Observer” and subsequently presented the bound volumes to Ossett Library.

Coming back to Eli Townend’s early work experience; he worked for a time at Healey Old Mill and then as a rag grinder for Mr. Henry Westwood, who had successfully contracted for the rag grinding at the Ellis Brothers’ Victoria Mill. However, always seeking to improve his lot, Townend started to supplement his earnings by establishing an early take-away food business by selling hot peas to hungry pub-goers who were wending their way home after an evening’s drinking in the many hostelries around Ossett. In the 1860s, wearing the cotton smock, which he only discarded as part of his normal daily wear when he retired from business forty years later, Eli Townend was a familiar figure to the residents of Ossett with his billy can of hot peas in the Market Place.

Townend was probably heavily influenced by his time at the Temperance Saloon because in his earlier days he was a teetotaller and non-smoker. This lasted until he was 35 years of age, but he always declared that he was “a teetotaller in principle, only lacking in practice.”

Always thrifty, Townend saved the money from his work as a rag grinder and from his hot pea venture until the real turning point came in his career. He saw and, importantly understood, how some enterprising Ossett men were doing well in the rag business, which was taking over from cloth production in the town as the main commercial activity. Townend speculated and spent all his savings on buying a bale of rags, which he then sold on at a good profit.

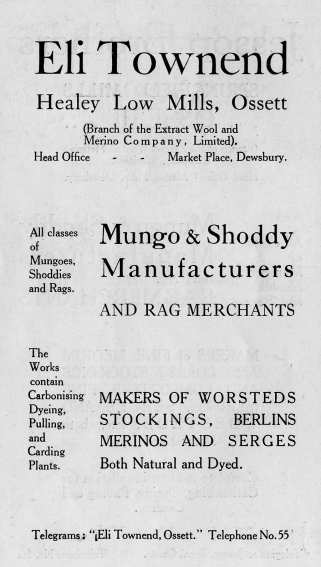

At first, Townend was in partnership with a friend and the business blossomed. Eventually, the partnership was dissolved and Eli continued in his own right for another 30 years or so as Messrs. Eli Townend from 1870 at Healey Low Mills as a mungo and shoddy manufacturer. Townend was a tenant of Healey Low Mill, but didn’t own the place outright. Although the business was established before the great rush of competition began and during a period of good profits, Townend was able to steer the company through some difficult periods in the intervening years with a mixture of shrewdness, sound judgement, hard work and careful business methodology.

As a businessman, Eli Townend had a reputation for straight dealing. With him, a personal undertaking was as good a security as a legal bond and he gained the complete confidence in those with whom he dealt.

As an employer, he maintained excellent relations with his work people and whilst he required a fair day’s work for a fair day’s pay, he used to say that a request for an increase in wages was an offence to him, because when a man’s work was worth more, he did not need asking. In 1900, Eli Townend retired from business, handing over control of the firm to his youngest brother George Townend.

At the same time, in July 1900, Messrs. Eli Townend joined the Extract Wool and Merino Co. Ltd. syndicate, which amalgamated several other Ossett mungo & shoddy businesses such as Giggal & Clay, Jessop Brothers and Fitton & Sons (based in Earlsheaton, but the Fittons lived in Ossett) in order to maximise buying power and to reduce business overheads.4 The firm was still trading as “Mesrrs. Eli Townend” as late as 1927. 5

FAMILY LIFE

Eli Townend married Ossett girl Sarah Ann Lockwood in the March 1868 quarter in the Dewsbury Registration District (probably in Ossett). They had at least four children: Emma born in 1868, Hannah born in 1873, a son Harvey born in 1875 and Ada born in 1877. Sarah Ann Townend died in the June quarter of 1898 aged 55 and Townend married his second wife Eleanor Clarkson in the September quarter of 1898, just a few months after his first wife had died. Eleanor herself died in Huddersfield, aged 48 in 1908.

In the 1881 and 1891 censuses, Eli Townend was listed as a mungo manufacturer living with his family at “Calder Villa” in Healey Lane not far from Healey Low Mill. By 1901, he is living with his new wife Eleanor and son Harvey at “Calder Villa”, but now as a retired mungo manufacturer. It is thought that “Calder Villa” in Healey Road was long-since knocked down, but in Townend’s time the house had huge greenhouses and all kinds of interesting plants and ornaments in the garden. When Eli Townend died in 1910 he left his house to his son Harvey Townend.

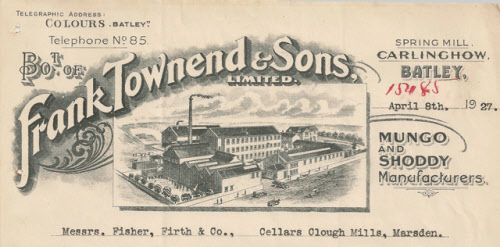

Eli Townend’s younger brother Frank Townend also started out in Ossett as a rag merchant, but after a family fall-out, he moved to Cut End Mill in Dewsbury and then later bought Spring Mill at Carlinghow, Batley in 1903. The billhead dated 1927 to the left suggests that Frank Townend & Sons were doing quite well at Spring Mill, which clearly was quite an extensive operation. Two of Eli’s brothers, Walter Townend and Harrop Townend were also rag merchants in Ossett. Youngest brother George Townend was part of the Eli Townend business management team at Healey Low Mill.

Eli Townend’s younger brother Frank Townend also started out in Ossett as a rag merchant, but after a family fall-out, he moved to Cut End Mill in Dewsbury and then later bought Spring Mill at Carlinghow, Batley in 1903. The billhead dated 1927 to the left suggests that Frank Townend & Sons were doing quite well at Spring Mill, which clearly was quite an extensive operation. Two of Eli’s brothers, Walter Townend and Harrop Townend were also rag merchants in Ossett. Youngest brother George Townend was part of the Eli Townend business management team at Healey Low Mill.

Although Townend wasn’t able to write anything more than his own signature and was never able to read, this didn’t deter him from a lifelong quest for knowledge. He simply got his family and friends to read to him from books and newspapers. This greatly increased his already formidable intellectual capacity, which was limited in his youth by the handicap to his eyesight that dogged his life. Greater wealth allowed him to indulge in a passion for foreign travel and he visited several European countries, Egypt and the USA. On all these visits he collected mementoes of his journeys including many rare specimens. He collected among other things a valuable museum of natural history specimens housed in the greenhouses at his “Grange View” home on Healey Road.

A LONG PUBLIC CAREER

Townend was to commence an impressive public career in 1882, in his mid-thirties, when he was elected as a member of the Ossett Local Board and the Dewsbury Board of Guardians (who dealt with the Poor Law at the Dewsbury Workhouse, which included the Ossett poor.) Always a controversial figure, largely because of his negative stance on the vaccination of children against diseases such as smallpox, Townend’s election to the Ossett Local Board was opposed by those who didn’t know him better or appreciate his abilities. In his election address to the Local Board he protested against the “scurrilous assertions and slanderous statements, which are freely scattered”, assertions which as the “Ossett Observer” remarked at the time, “he appeared to have suffered less than his fellow candidates for his severest critic in print admitted him to be a man of undoubted energy and ability.” This was an accurate description, for on the Local Board, Townend proved to be one of the most active and progressive members. He possessed a ready flow of blunt yet vigorous language, a rough but keen humour and with a good strong voice, he was an able and telling speaker.

One of his first important acts at the Ossett Local Board was to join those calling for the construction of public offices and, in 1906, the Town Hall was finally built. Although supposedly a Liberal in politics, Townend demonstrated socialist ideals well before socialism and the Labour Party were fashionable. For example, in a time when most working class people rented the property that they lived in, he pressed for rates to be levied on the owners of the property instead of the occupants. Similarly, Townend wanted manufacturers to pay water bills, maintaining that otherwise the working classes would suffer hardship. He wanted public baths and recreation grounds building in Ossett and was the lead proponent for the purchase of the Wesley House estate for a public park and public offices following the death of William Gartside. Not always successful in some of his lofty aims, nevertheless he was a strong supporter for a School Board and for a public cemetery. He remarked in one of his characteristic speeches that if sanitation continued to improve, the cost of which was “saved in coffins”, then a cemetery would not be needed because “they had got the death rate to 10½ (per thousand head of population) and if they knocked that off, they would all live forever.” Following a fire at a local mill, he proposed that the question of purchasing a steam fire engine should be referred to a “thinking committee”. He strongly supported the first resolution passed by the Ossett Local Board in favour of applying for a Charter of Incorporation. However, in a speech in which he said that the dignity of municipal borough was desirable as long as there was nothing extra to pay for it. For one of Ossett’s greatest improvements, the construction of Station Road, Townend was on the the side of the opponents, who were strongly against the scheme. Upon the incorporation of the borough in 1890 he was elected one of the first members, but on the expiration of his term of office, he did not seek re-election, retiring from public life altogether, but he was prevailed upon to become a member a candidate in 1903, and he continued to sit until his death.

In October 1889, Townend, now calling himself an Independent Liberal candidate, was elected a member of West Riding County Council and later, after the death of Mr. John J. Mitchell an Alderman. He was elected in the face of considerable opposition from amongst others, the Medical Officer of Ossett’s Local Board, Dr. John W. Greenwood, who at a selection meeting proposed “that Mr. Townend is not a fit and proper person to represent the division on the County Council for the next three years.” Townend had strong, even extreme views on many subjects, but particularly on compulsory vaccination. He and his brothers were fined for not allowing their children to be vaccinated and this was the root of Dr. Greenwood’s opposition to Townend. Other Ossett notables of the time such as Mark Wilby and Charles T. Phillips were also strongly opposed to Eli Townend being their representative on the West Riding County Council. However, Townend had strong support from the Ossett Conservatives led by his uncle, Gawthorpe schoolmaster, Benjamin Harrop.6 Once successfully elected, Townend lobbied for the management of the Poor Law to be transferred to the County Councils.

At one period of his life, he was a member of the Ossett Local Board (which met fortnightly), the Dewsbury Board of Guardians (1882 -1894) and the West Riding County Council and on each of these bodies he was known for his strongly independent attitude. Though wealthy himself, Townend respected neither wealth or person. A “son of the soil”, his sympathies were always with the working classes. As a member of the Local Board and the Board of Guardians, he fought many a protracted battle on their behalf. As a guardian, his sympathies with the poor who applied for relief were profound and usually exceeded his legal mandate. He opposed salary increases for Workhouse officials, insisting that the poor rate was for poor people and not to pay their exorbitant salaries and to him, money spent on lawyers was money thrown away. This made him popular and he was assured of being elected to any office where Ossett people had the power to elect him. A formidable opponent in local elections, Townend was always elected at the top of the poll (with only one exception), or returned unopposed. However, he declined the chairmanship of the Local Board and the opportunity to become the mayor of Ossett.

OPEN-HANDED GENEROSITY

From what has been written, it is easy to see how Eli Townend made many political enemies with his uncompromising stance on life. However, this was a man who practised what he preached and this excerpt from his obituary in the “Ossett Observer” reveals his true philanthropic nature:

“But perhaps the phase of his character which earned him most of the respect and popularity in which he was held was his large-heartedness and his extreme generosity to those in need. His bluff, rugged exterior; the robust humour which, especially in the time of his vigour, was a marked characteristic; his independent, freelance, hail-fellow-well-met attitude, were combined with a tender gentleness towards those in circumstances the hardship of which he himself had felt. To hear of a needy case was to put his hand, often deeply, in his pocket, and he heard of them frequently for he was the one to whom scores nay, hundreds of persons turned for assistance in their difficulties. To render it was to him a pleasure. At Christmas, it was his practice to distribute blankets and coals among poor persons who were in receipt of poor-law relief. He has given as many as ninety or a hundred loads of coal in a year in this way. Only last Christmas, we believe the number was about ninety. Every local cause, which had for its object the relief of suffering had in him a liberal supporter. He was the mainstay of the Ossett District Nursing Association, an organisation in which he took a deep interest, subscribing handsomely to its funds. Public celebrations were several times made the occasion for liberality towards the old or poor folk of the borough, or the children, the latter of whom, as well as the former had in him a good friend. During his membership of the Dewsbury Board of Guardians, the inmates of the workhouse had reason for regarding him in the same light. On one occasion, all the workhouse children were conveyed to his residence in Healey-road and there entertained by him. It may be stated on good authority that his charitable dispensations in these ways amounted to several hundred pounds annually, over a long period of years.”

DEATH AND THE FUNERAL

Eli Townend died on Saturday, 16th July 1910, aged 65, after several years of failing health that had caused him to sometimes miss taking his seat on Ossett Town Council. Latterly, his condition had gradually become worse and he was rarely able to venture from home. His heart was failing and he suffered from bronchitis. The end was hastened by a stoppage of the bowels and a day or two before he died, his condition became critical, causing him to lapse into a coma. At this stage, there was no hope and he never rallied, dying about seven o’clock on Saturday morning. His death caused widespread regret among the people of Ossett.

Eli Townend was interred at the Wesleyan Burial Ground, South Parade, Ossett on Tuesday, 19th July 1910. The flag at the Town Hall was hoisted at half-mast and a muffled bell was tolling. Flags floated at half-mast over Ossett Liberal Club and on other building in the town. Blinds were drawn on many of the houses lining the route of the cortège. Near his house in Healey Lane, a large number of people, mostly dressed in funeral clothes, watched the funeral procession and hundreds if others watched the cortège on its way to the burial ground. The procession was an unusually long one; the longest of this sort remembered in Ossett at the time. There were between thirty and forty mourning carriages bearing the chief mourners as well as members and officials of other public organisations, the work people from Messrs. Eli Townend, friends and acquaintances of the deceased as well as many representatives from business firms in the Heavy Woollen District. A large number of beautiful floral wreathes were received and filled two of the carriages.

In the vicinity of the burial ground a large crowd assembled. The service, both in the chapel and at the graveside was conducted by the Rev. C.S. Reader, superintendent minister. Owing to the large number of persons attending the funeral, the public were excluded from the burial ground during the service. Several members of the Oak and Ivy Lodge of U.A.O.D. of which the deceased was an honorary member and some of the oldest workmen of Messrs. Eli Townend acted as bearers. The funeral arrangements were carried out by Mr. G. Heald.

Eli Townend left £34,000, a considerable sum in 1910, as well as several Ossett properties, in addition to his home in Healey Road “Calder Villa”. In the 1911 Census, Eli’s second wife Eleanor is recorded as a widow still living at “Calder Villa” with stepson Harvey Townend.

References:

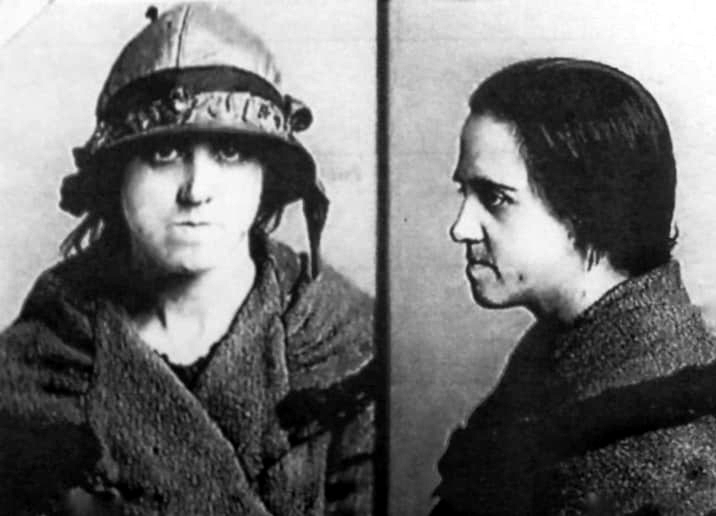

When Thomas Pierrepoint removed the safety pin from the gallows at Strangeways Prison at 9 a.m. on the 24th June 1926, the diminutive figure of 31 year-old Mrs. Louie Calvert dropped through the hatch and in 20 seconds her life had ebbed away at the end of a hangman’s rope. Resigned to her fate after her conviction in court, she went to her maker quietly and in dignified fashion. Louie Calvert was one of the few British women ever to to be hanged and this was the first female hanging at Strangeways since that of Mary Ann Britland in 1886.

Above: Louie Calvert’s prison photograph taken shortly before she was hanged. This is the only known picture of Louie Calvert and is courtesy of Donna Johnson.

Her tragically short life had never been easy and Louie Calvert (nee Gomersal) had been dodging the long arm of the law ever since she was sixteen years of age. She had given birth to two children: a girl Annie and a son Kenneth, both out of wedlock, whilst she worked as a prostitute in the seedy parts of Leeds. There’s no doubt that she led a double life, fabricated by a web of intricate lies and she alternated almost “Walter Mitty” like between a make believe world as a Salvation Army convert and the grim reality of scratching out a life in industrial Leeds after WW1. When you anlayse her story, sometimes it is hard to decide who really was the victim. Did Louie Calvert really murder two people or was she so mad, bad and committed to petty crime that the judge and both the prosecution and defence lawyers effectively gave up on her?

Louie Gomersal was born in Ossett on the 12th January 1895, the daughter of woollen weaver Smith Gomersal and his second wife Annie Elizabeth (nee Clark). She was baptised at All Saint’s Church, Wakefield on the 14th April 1895. In 1901, the Gomersal family were living at Glenholme Terrace in Gawthorpe. Louie was the fourth of five children in the family. By 1911, the family had moved to live in nearby Pickersgill Street, and Smith Gomersal was now working as a caretaker at a school with Louie employed as a cloth weaver.

At the age of sixteen, in 1911, Louie Gomersal was bound over at Dewsbury Magistrates Court for for stealing £2 and for stealing 10 shillings in two separate offences of theft. This was just the start of her criminal career, and in July 1912, aged 17 years, she was sentenced to a year in Borstal for stealing a purse, a ring, a three-cent piece and a farthing from Mary Ann Carter on 25th September 1911 in Batley and £1 in money from Patrick Reynolds, also in Batley, on the 26th April 1912.

Louie Gomersal was short, thin, undernourished, not particularly attractive and coarse in manners. In fact, she was less than five feet tall, but what she lacked in height, she made up for in assertiveness by way of a very strong personality. It was said that some people found her intimidating and they were genuinely scared of her.

After leaving her home in Ossett, Louie Gomersal moved to Leeds, where she lived a hand-to-mouth existence as a prostitute. In about 1916, she gave birth to an illegitimate child called Annie, who went to live with Louie’s sister in Ossett. She also had a second child in 1919, a boy called Kenneth on whom she doted. Louie was fond of using an alias and for the Salvation Army meetings she sometimes attended, she used the name Mrs. Louise Jackson and also Edith Thompson when she was on the game.

In 1922, Louie using her “respectable” alias of Mrs. Louise Jackson, went to work as a housekeeper for 49 year-old John W. Frobisher, who lived in Mercy Street, lying between St. Philips Street and Wellington Lane, near the city centre of Leeds. On the 12th July 1922, Frobisher’s lifeless body was found 400 yards away from his house, near Monk Bridge, floating face down in the Leeds – Liverpool canal. He had a fractured skull and a massive head wound. Bizarrely, although he was found in the water fully clothed, Frobisher’s boots were missing.

Although suspicion fell on Louie Gomersal initially, the police did not investigate further. At the inquest, Louie appeared and she stated that she had pawned John Frobisher’s boots. Had Frobisher walked to the canal with no boots on? He lived a quarter of a mile away from the canal, yet the inquest recorded a verdict of death by misadventure and it was assumed that he had simply drowned. Louie continued to live in Frobisher’s Mercy Street house until she was evicted a few months after his death for the non-payment of rent.

Above: Mercy Street, Leeds. The home of John Frobisher who was found dead in the Leeds-Liverpool canal on the 12th July 1922.

Arty Calvert, a poor night-watchman lived at 7, Railway Place in the Pottery Fields area of Hunslet, Leeds. In 1924, Louie went to live with Arty, ostensibly as his housekeeper, taking along her five year-old son Kenneth. Soon Louie and Arty were sleeping together and, after a while, Louie claimed that she was pregnant by him. Arty Calvert was old-fashioned and decided to do what he saw as being the right thing, so he offered to marry Louie. In the summer of 1925, the couple married in Hunslet, Leeds. Meanwhile, Louie managed to play out the deception that she was pregnant for some time. When no baby arrived. Louie initiated an elaborate web of lies. She wrote a note to herself, which she showed to the poor unsuspecting Arty, claiming it was from her sister in Ossett whom had invited her to stay during her confinement. After a brief visit to Ossett, she sent Arty a telegram to say that she had arrived, but in fact Louie had by then returned to Leeds.

Somehow, to keep the deception going, Louie had to produce a baby and she did so by the simple means of advertising in the local Leeds paper, offering to adopt a newborn child. A teenager from Pontefract had recently given birth to a baby girl and her mother saw Louie’s advert in the paper. Giving birth to an illegitimate child in the 1920s was regarded much differently to today and there was great stigma attached to such events, which were all too common. Adoption provided a way out for the Pontefract girl and her mother. It didn’t take long to arrange for the baby girl, who had been named Dorothy, to be handed over to Louie Calvert. Pretending the little girl was hers, and to explain her absence, she told Arty that the newborn was in hospital.

Instead of being at her sister’s home, Louie Calvert had actually taken up lodgings just two miles away from her husband’s house at Amberley Road, Leeds with 40 year-old widow, Mrs. Lily Waterhouse, a part-time prostitute and psychic, who to make ends meet rented out a spare room to working girls. Lily Waterhouse’s husband George had died aged 59 years about a year previously. She now lived in grinding poverty and squalor in the tiny rented terraced house with wooden boxes serving as tables, bare plaster walls and bare floorboards, except for newspapers under the mattress. Mrs. Waterhouse had been in poor health for some time and her post mortem revealed that she suffered with both scabies and body lice. Despite her ill-health, she survived mainly by prostitution and often entertained gentlemen back at the house. It was reported in one of the local newspapers by one correspondent that “she was suffering from a social disease”, which was a euphemism for some kind of venereal disease, although Lily’s post mortem didn’t substantiate this claim. It is easy for us to look critically at the morality of Lily Waterhouse, but these were very difficult times during a period of industrial unrest and staggering poverty. Making ends meet would have been difficult for a 40 year-old widow.

Above: Amberley Road, Wortley, Leeds, where Louie Calvert murdered Lily Waterhouse.

Louie Calvert’s role was to act as some kind of maid servant or companion for Mrs. Waterhouse, though as we see later, they worked together as prostitutes. Unfortunately, the two women soon proved to be incompatible and to make matters worse Louie refused to do any housework, and then started stealing Lily’s bedding and crockery, which she pawned. Discovering the thefts, Lily Waterhouse went to the police in Leeds to complain that her belongings had been stolen. Detective-Sergeant John Holland was assigned to interview Mrs. Waterhouse on the 31st March 1926, and he was well aware of her minor notoriety. Proceedings were started against Louie Calvert for theft, but that same night Mrs Lily Waterhouse was murdered. The killing had been a brutal one involving a “prolonged struggle before the knock out blow” and a “penetrating wound down to the bone” at the back of the head prior to strangulation. Lily had also been tied up.

Several neighbours heard the sound of a disturbance and loud banging from inside Mrs. Waterhouse’s house. Shortly after the commotion stopped, Louie left the house with the baby and was carrying a canvas bag with some crockery in it. One of the neighbours, a Mrs. Clayton commented to Louie that she had heard Mrs. Waterhouse making strange noises. Louie replied “Yes, I have left her in bed crying because I am leaving her.” Louie Calvert then caught the tram back to her marital home and her unsuspecting husband Arty.

Later that evening a policeman called at Amberley Road to find out why Mrs. Waterhouse hadn’t returned to the police station to sign the complaint she had made against Louie Calvert. After hearing about the strange noises from the neighbours, the policeman obtained a key and let himself in. There he found Lily Waterhouse lying on her bed, with her hands tied, battered about the head and strangled to death. She was fully dressed, except for her boots, which were missing. There was no sign of a struggle and the dust in the room had not been disturbed, suggesting she had been killed elsewhere and carried to her room once dead. The killer had cut up some cloth to tie Lily’s hands and feet, yet there must have been something else used to strangle her because the ligature marks around her neck were wider than those caused by the strips of cloth.

At last Arty had his wife back, and also what he thought was his baby, little Dorothy. This was a brief happy time for the Calverts. Unknown to him and bordering on the unbelievable, Louie had gone back to Amberley Road at 5 a.m. the next morning and filled a large suitcase with the few possessions left in Lily Waterhouse’s home. Her compulsion to steal hadn’t been diminished by the horrors of the previous evening and by the murder of Lily Waterhouse. Several neighbours at Amberley Road had seen Louie Calvert leaving the house at 5:30 a.m. with a large suitcase. Arty Calvert was also surprised to see the suitcase, that had not been there the night before, in the downstairs room when he got up the next morning. Even more surprisingly, when she returned to Amberley Road to steal more things, Louie had left a note to say she was collecting items that had been given to her by Lily Waterhouse. Had she not done that, there is a real possibility that she could have escaped undetected. Lily Waterhouse’s neighbours had no idea who she was and she had only been at the house about three weeks.

The police in the form of Detective-Inspector Pass soon tracked down Louie Calvert and made their way to the marital home at Railway Place in Hunslet. When Louie opened the door, she was wearing Lily Waterhouses’s boots and scarf. Maybe this was an echo of something that happened four years previously when her then employer John Frobisher had been found face down in the Leeds – Liverpool canal with his head bashed in and also missing his boots. The police worked quickly and efficiently and found Lily Waterhouse’s few possessions in the house and in the suitcase. Louie was arrested, but crucially not charged until 24 hours later, which formed the basis of an appeal later on.

Remanded in Armley Prison, and by now an ugly, wizened woman of 31 years without a tooth in her head, Louie was finally brought to trial at Leeds Assizes on the 6th and 7th May 1926, where, after a two-day court case, she was found guilty of the murder of Mrs. Lily Waterhouse. With the prisoner condemned by the jury, the judge Mr. Justice Wright, had few reservations about imposing the mandatory death sentence on the woman that stood in the dock before him. It was said that Louie Calvert received the notice of the death penalty with an air of calm indifference.

During her incarceration, Louie Calvert was described as below by the prison authorities:

“The prisoner has been known as a prostitute of a low type in Leeds for some years. She has a bad record of theft and house breaking that started from the age of 15. She has two illegitimate children aged 9 and 6 years. The prisoner is idle and of very dirty habits.”

Details of the trial are almost non-existent. Transcripts have not survived and there were no newspaper reports after the General Strike ended. Some information has been forthcoming from her Appeal, held on the 7th June 1926, which was fought on the grounds that “she was not charged within 24 hours after her arrest” and that during that time, she was subjected to an amount of questioning that exceeded what was allowable.

The appeal failed and the Lord Chief Justice responded that “nothing in the present case suggested that the police had gone beyond their duty.” He also felt that his summing up had been both “clear and fair”. He further commented that “Calvert did not give evidence, although her defence was that she was NOT the person who killed Mrs. Waterhouse.” Clearly, Lord Chief Justice failed to maintain a neutral attitude towards the fact that Louie waived her right to give evidence on her own behalf. He concluded the hearing by dismissing her appeal without calling upon the Crown to argue, and without legal obligation to consider the fact that 25 witnesses had appeared for the prosecution, whilst NONE had appeared for the defence. It seems likely that the Judge and the Defence deemed it likely that Louie Calvert was an unsuitable witness who would not make a good impression on the jury due to her social class, lack of education, personality and general demeanour.

Louie’s final act of desperation was to tell one more lie in the court room in a last bid to save herself by claiming that she was pregnant. Whilst it was hard to find any redeeming features with Louie’s personality, there was plenty of opposition to her hanging. Mr. J. Lambert, a Leeds City Councillor who observed the trial declared that he was “full of pity for the poor woman, whether she was guilty or not. She was a thin, wan-looking creature only weighing a few stones. I should never legislate on the lines of hanging for women.” Meanwhile, Dr. Watts an MP, felt sufficiently concerned about Louie’s supposed pregnancy to raise the issue with the Home Secretary through a Parliamentary question. Sir William Joynson-Hicks, the Secretary of State answered that: “Any doubt which may have existed as to the prisoner’s condition has since been dispelled, and it is now certain that there was no pregnancy.”

Nevertheless, as the date of Louie’s execution drew nearer, strenuous efforts were made to obtain a reprieve. The Labour MP for Consett, the Reverend Sir Herbert Dunnico organised a petition, which was signed by 3,000 people, many from Louie’s home town of Ossett. There was also a motion for an address praying His Majesty the King to exercise his Royal Prerogative in the case of Louie Calvert, signed by six Labour MPs. However, it was all to no avail and Louie Calvert was moved to Strangeways Prison in Manchester to await her fate.

Whilst awaiting her execution, Louie Calvert wrote her “Life Story”, which included her account of the events surrounding the death of Lily Waterhouse:

“I got into the company of the young women with whose death I am charged. We used to go out at night and visit public houses with the intention of getting hold of any man who had money, to get them drunk, then rob them of any money they had left. The last Sunday I was there, this woman brought a man home supposed to be a soldier from Beckett’s Park hospital for wounded soldiers. After he had been there a few days we began to quarrel about him. She wanted him, and he wanted me, but I wanted neither. I wanted to leave them and go home again as it was beginning to get a little bit too hot. The detectives were on our tracks and we couldn’t go out without them pulling up and getting us fined.

Well, on the Wednesday night, the day I was going to leave her, we went out and had a few drinks with this man and he fetched half a dozen pints of beer and stout home. After about half an hour we all started to quarrel and it got to fighting. Oh, the drink, it is the ruination of everything, for we do lots of things in drink and temper that we are most sorry for afterwards. Well he said something nasty to her and she landed out with her fist at him and they both rolled on the floor. When she got up and struck out again, I picked up the poker, which happened to be the nearest thing to me and my intention was to strike the man and make him leave off hitting her. Instead it struck her on the head through him dodging out of the road and she fell dead at our feet. He went mad and then got hold of a belt, strangled her and carried her upstairs. I got out and got home. God knows how I did it. I don’t.”

Louie’s account makes it quite clear that a man was present at the killing. A Home Office memo confirmed that the legal teams at the trial had knowledge of the man being present at Amberley Road prior to her trial, a fact borne out by the neighbours of Mrs. Waterhouse who had seen the man. The police, when they visited Louie Calvert on the day after the murder, had found a piece of paper in her handbag with the (Canadian) address of a man called Crabtree and enquiry was made regarding the recent movements of a miner named Frederick Crabtree, who was an out-patient at Beckett’s Park hospital.

Despite this evidence being provided by the Leeds police, when the Prison Governor passed Louie’s “Life Story” to the Home Office after her conviction, a civil servant noted “this is the first time the prisoner has told her story.” Fred Crabtree was actually summoned to appear in court as a witness, but he was never called.

Above: Strangeways Prison where Louie Calvert was hanged and where she was buried in an unmarked grave.

Louie’s last request, before she was executed, was to see her 6 year-old son Kenneth and this was granted on her last afternoon when Arthur Calvert, her husband and Leah, her sister-in-law with young Kenneth all came to say goodbye. The meeting lasted half an hour and at the end, when the boy pathetically appealed to his mother to come home, he was told that she had to go to London to see the Queen.

On the 24th June 1926, the day of the execution at Strangeways Prison, a crowd of around 500 people gathered outside the prison walls. A little later than the usual time of 8 a.m. and upon a signal from the Prison governor, Thomas Pierrepoint, Britain’s most established hangman entered Louie’s cell, accompanied by two male prison warders. A woman warder told her to stand up and Pierrepoint took her arms and quickly strapped her wrists behind her back with a leather strap and then led the way out of the cell. Louie was led into the execution chamber and stopped whilst Pierrepoint marked out the letter “T” precisely over the divide of the trap doors. Pierrepoint’s assistant William Willis then put leather straps around her ankles and thighs. A white handkerchief was placed on her head, followed by a hood.

Pierrepoint slipped the safety pin out and the trap doors opened. Louie Calvert was dead in less than twenty seconds and at about nine o’clock, a strange hush fell upon a section of the crowd when a bell inside the prison began to toll in faint, ghastly tones to announce that the deed had been done.

Looking back on all the evidence, it has to be said that there must be some serious doubts about Louie Calvert’s conviction for the murder of Lily Waterhouse. Was Fred Crabtree really the murderer? There was little sympathy from the Lord Chief Justice given her criminal past and her appearance. However, there seems little doubt from Louie’s confession in her condemned cell that she murdered John Frobisher in July 1922. Sadly, we shall never know the truth about what really happened at Amberley Road.

References:

1. Gomersal family data – courtesy of Alan Howe, Ossett

2. “Yorkshire’s Murderous Women – Two Centuries of Killings” by Stephen Wade

3. “Reconceptualizing Critical Victimology: Interventions and Possibilities” by Dale Spencer and Sandra Walklate

4. “Dead Women Walking – Executed Women in England and Wales 1900 – 1955” by Annette Ballinger, a thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, September 1997.

5. “Daughters Of Cain: The Stories of Eight Women Executed since Edith Thompson in 1923” by Renee Huggett and Paul Berry

Thomas Tomlinson Cussons.

Thomas Tomlinson Cussons was born in Hull in 1838, the son of George Cussons and his wife Jane (nee Moss). Thomas had an older brother, William Henry. In 1867 he married Elizabeth Ashton at Louth in Lincolnshire. Some time between 1868 and 1870 he moved to Leeds and in the 1871 census he was recorded as being a chemist and druggist at 31 Stocks Hill. Thomas and Elizabeth had three children, John William Cussons was born in 1867 in Louth, Florence Cussons in Leeds and Alexander Cussons also in Leeds.

In 1880 he took over the chemist and druggist business of Richard Moore. He also took the position of postmaster at this time from Mr. Moore. He was already qualified as a chemist and druggist by examination.

The Ossett Observer reported at the time he had been working as a chemist in Louth, dispensing for doctors Sharpley & Higgins. I can find a Dr Sharpley in Louth in the 1860s but no Dr Higgins. In the 1861 and 1868 directories for that town there is no Cussons Chemist advertised so I assume he was working for another chemist before taking over his own business in Leeds. There was one chemist in Louth, Thomas Simons, who was also postmaster. Maybe Thomas worked for Mr Simons and learned his postmaster skills there too. By 1874 advertisements in the Leeds Mercury mentioned him as being at the Stocks Hill post office.

In his advertisement in the local press announcing his arrival in Ossett, he stated that he skilfully extracted teeth, as well as having:

“a large and well assorted stock of patent medicines at reduced prices. A choice assortment of hair, tooth, nail, shaving, painters and other brushes. Also combs, toilet soaps, sponges, perfumery and other toilet requisites. The same quality tea and coffee, for which this establishment has so long been noted, will also be kept in stock, and may be relied upon. Agent for W & A Gilbey’s wines and spirits, also for Bass’s beers and Guinness’s stout”.

Apart from also producing his own baking powder, an essential requisite in those days. he provided veterinary medicines, which he would continue to make up from Mr. Moore’s own recipes. In the 1881 census, he is recorded as living in Dale Street with his wife, three children and servant Charlotte Robinson, aged 19 years.

The premises in which he took over Mr. Moore’s business were in Wesley Street, facing inwards towards the market place, roughly in front of where the Lloyds TSB bank now stands. In 1882, two years after moving there, he had to abandon his premises as they were compulsorily purchased by the Local Board of Health for the widening of Wesley Street and he moved business to the other side of the Market Place. The old premises were sold by auction on Monday, July 17th 1882 and it was reported that the energetic demolition of the old house commenced the same evening, for the recovery of the building materials. His address was now “Commercial Buildings”. About this time, he was also refused a beer licence and had to give up that part of his trade, which had been carried on a long time by Mr. Moore.

Mr. Cussons had three children, John William (b. 1867), Alexander Thomas (b. 1875) and Florence (b. c1870). In May 1889 it was announced that his son John William had passed the Pharmaceutical Society’s examination, and was now qualified to register as a chemist and druggist. He had been educated at Wakefield Grammar School, and commenced work in the post office in May 1882 as assistant to his father, a few months before their move of premises.

In 1892 Thomas Cussons retired his position as postmaster. He had seen 20 years of postmanship, the last twelve years of which were as a postmaster. For a while he had been running another chemist’s business in Swinton, near Manchester, with his son John William Cussons as partner. He now took the opportunity to move to take personal charge of that concern. John William Cussons took his place as postmaster, and was presented with a handsome pipe and a silver mounted walking stick by the staff of the Post Office.

In 1892 Thomas Cussons retired his position as postmaster. He had seen 20 years of postmanship, the last twelve years of which were as a postmaster. For a while he had been running another chemist’s business in Swinton, near Manchester, with his son John William Cussons as partner. He now took the opportunity to move to take personal charge of that concern. John William Cussons took his place as postmaster, and was presented with a handsome pipe and a silver mounted walking stick by the staff of the Post Office.

Pictured Right: John William Cussons b. 1867.

The business in Ossett continued to trade under the name of Cussons & Son. This was to be an important year in the life of John, for on Wednesday 22nd June of that year he married his fiancée, Catherine Wilby at South Ossett Wesleyan Chapel. She was a daughter of woollen manufacturer Mark Wilby of Manor House, Manor Lane.

By the end of 1892 they were advertising that they had a large stock of chemical apparatus and pure chemicals: “important to chemistry students”. An illustrated price list was free on application.

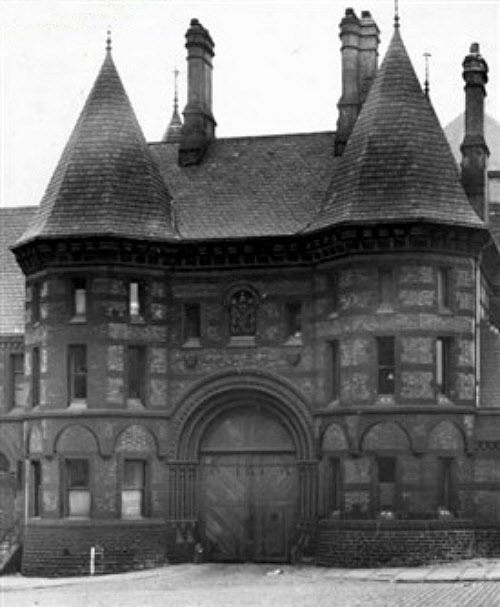

It appears business was doing very well, for in April 1893 it was announced that Cussons had secured a site for building new premises for his shop and Post Office, on the corner of Prospect Road and the new Station Road. This was a new thoroughfare in the town, and was being rapidly developed. The “Dewsbury Reporter” at the time stated that it “was fast becoming the handsomest street in the Heavy Woollen district”. It was to be a grand building, with Mr. Cussons’ residence forming part of the building, his shop being on the corner, and Post Office business having a frontage of 27ft on to Station Road. A stone, carved with his entwined initials was to be set into the end wall. In early March 1894 the premises were occupied for the first time, the new Post Office opening on Tuesday, 6th March. On 22nd March, John William gave a dinner at the Coopers Arms to celebrate the opening of his fine new premises.

In 1895 John William was again applying to the Ossett Brewster Sessions to gain a licence to sell beer for consumption off the premises. However, it was pointed out that within 300 yards of his shop there were eleven licensed houses, of which four were fully licensed, the other seven being beer houses. On the grounds of the number of licences already issued in the area, his licence application was refused.

In 1897, John William Cussons was elected Hon. Secretary of the newly formed National Sub-Postmasters Association, however, after only two years in the position he announced at their annual conference that he would have to retire from the position and he was instead elected as vice- president. Two years later in October 1899 the “Sub-Postmaster”, the official magazine of the National Federation of Sub-Postmasters, gave a portrait of John William, and biographical details. This portrait was reproduced in the “Chemist and Druggist” journal, which also gave the information that Mr. Cussons was also a member of the executive of the Dewsbury & District Chemists’ Association. In June the following year he was the recipient of a beautiful marble timepiece, as a token of respect of the sub-postmasters for his services to the national federation.

However, later that year it was announced that John William Cussons would be retiring his position. At the same time he was disposing of his business as a chemist and druggist. This was in consequence of having purchased the manufacturing drug business of Messrs. Sherratt & Co., of Harpurhey, Manchester. The latter had been amalgamated with a similar business in the same district belonging to his father, Thomas. The whole would be carried on as Cussons, Sons & Co., with John’s younger brother Alexander now being heavily involved in the family business. It was at this time that the Post Office in Ossett was to be separated from the family’s other business ventures and became independent. The Cussons business was to go from strength-to-strength, to become the household name of Imperial Leather we are now familiar with.

Ossett-Born Millionaire

At least one son of Ossett lived to become a millionaire, founding a firm which is known the world over. He was Alexander T. Cussons, younger son of Mr. T. T. Cussons, post-master and chemist, of Ossett Market Place. Father and son moved to Swinton, Lancashire where they began the manufacture of chemist’s products such as brilliantine and scented cachous, salts, etc.Mr. A.T. Cussons expanded the business and took over a derelict factory at Kersal Vale, Manchester, which he turned into a modern factory covering 14 acres. He concentrated on the manufacture of high-class soaps, cosmetics and talcum powder which are sold all over the world under the brand name “Imperial Leather”.

A nephew of W. Cussons is Mr. L.W. Cussons of Berry Lane, Horbury.

“Ossett Observer Jubilee edition”, July 4th 1964:

S. N. Pickard.

In November 1900 an advertisement appeared in the “Ossett Observer”:

“Mr. S. N. Pickard begs to announce that he has purchased the business of chemist and wine & spirit merchant, carried on successfully for many years by Mr. J. W. Cussons. Having had a large experience of the dispensing of medicines, analyses and pharmacy, he hopes to be accorded a fair share of the patronage from his many Ossett friends, and the public generally. The purest drugs and chemicals only employed. Patent medicines at lowest London prices. Note the address: S. N. Pickard, Member of the Pharmaceutical Society, Dispensing and Family Chemist, Station Road, Ossett”.

Samuel Norman Pickard, a native of Ossett, was educated at South Ossett Church of England school, and then at Ossett Grammar School, when it stood on the site of the present Town Hall. As a committed Christian, Pickard became a Sunday School teacher. He served his apprenticeship with George Saville, chemist, in Wakefield when he was 16 and qualified as a chemist from the South London College Of Pharmacy then later became a member of the Pharmaceutical Society after passing their examination, which included Latin, in the spring of 1886.

After this he went back to Mr. Saville for a short time as an assistant. He then moved on to become pharmaceutical dispenser at Clayton Hospital, Wakefield. Following this he took over the management of the business of Mr Handforth, chemist and dentist at 74 Manningham Lane, Bradford, around 1889 and subsequently acquired the business. He ran this business for 11 years before selling it to purchase the business of John William Cussons.

In March 1924 Mr. Pickard applied for transfer of his wines & spirits licence to new premises in Wesley Street, near to where the shop had stood, which Mr. Cussons had first taken when he moved to Ossett originally. The August 1st edition of the “Ossett Observer” for that year carried the advert:

“Change of premises: S. N. Pickard, chemist & optician, begs to announce that owing to expiration of lease he is transferring the business to larger and more commodious premises in Wesley Street, Ossett, which he hopes to open on Wednesday next, August 5th”.

This building was built around 1880 by Mr. J. Hampshire-Nettleton who ran his butchers shop from there before moving into the Market Place. Later, the premises were used as the town’s first Labour Exchange, before Mr. Pickard took up occupancy.

A little later, due to health reasons, he moved to Bridlington for a few years, but then moved back to Ossett shortly after war was declared. He celebrated his golden wedding anniversary on the 17th October 1943 at his home: The Knoll, West Wells Road. However, in November of the following year Pickard died in his 76th year. A photograph of Mr. Pickard was published in the “Ossett Observer” after his death. Mr. Pickard’s daughter carried on the business until his grandson, Mr. Ian Pickard Rigg, came out of the army and became manager of the shop in 1955.

Mr. Rigg had in his possession books in which prescriptions were recorded which had been dispensed, from earlier days. The first book contained 1,994 prescriptions. The last entry bore the date 1872 and the stamp of C. H. Lockwood, chemist, Dale Street, Ossett.

In August 1963 the floor space was increased by 50% after alterations. A new modern dispensary was built in a back room, which was formerly used as a kitchen. Shelves were fitted in the shop and stocked supermarket style so that customers could serve themselves from the displayed products. The shop offered a fine selection of wines and Mr. Rigg often travelled abroad to choose them.

The company had bought the business of D. Haigh, chemist of 140 Dewsbury Road, but after five years of being open this branch had to close in December 1970. It had run at a loss for the previous two years, with the staff of two being reduced to one.

Mathew Marsh

He was born in York in 1866, but the majority of his days as a youth were spent in Normanton, where his father, Mr. William Marsh, was employed by Messrs. Henry Briggs, Son & Co, colliery proprietors. After he left Normanton National School, In 1881, Mathew Marsh took employment with Job & Carr, chemists, of Normanton and Wakefield. He stayed there until 1887 and for the last five years there, he was an articled apprentice. His father left Normanton to take up the position of deputy at Old Roundwood colliery in Ossett, and after living in Alverthorpe for a short while he moved to Ossett where he lived for 36 or 37 years before he died on “Peace Night” in 1918.

After leaving Job & Carr’s, Matthew Marsh was employed for two years by Messrs. George Exley & Son, pharmaceutical chemists, Leeds, following which he became manager to Mr. John Day, chemist, Savile Town, Dewsbury. He was married in Leeds in 1891 to the daughter of an Armley builder, and shortly afterwards he moved to Great Stanmore in Middlesex, as manager to a chemist & druggist there. In 1895, he moved to Ossett where he commenced his business in Horbury Road, “Marsh’s Medical Hall”, opposite South Ossett Church, before moving to Victoria Buildings further along the road in 1900.

During his residence in Ossett he took a keen interest in public matters, and associated himself with many useful movements of the day. He was a staunch churchman as a sidesman at South Ossett Church and he also sat on the church council. For several years he was Hon. Secretary of the South Ossett Working Men’s Institute, and a founder of the club in Belmont House. In gratitude for his services here he was awarded in 1906 a handsome marble clock and bronze ornaments.

He first took interest in local government matters in 1909 when he opposed Mr. Walter Townend, an ex-mayor, in the East Ward, and was returned by 398 votes to 192, a considerable victory. In 1912 he had a landslide victory, and since there were no elections during the Great War, he was not contested until 1919, when he was opposed by Mr. Alfred Renshaw, whom he defeated by 567 votes to 543, after the keenest contest in the history of the ward.

Marsh always sat as an independent, not being affiliated to any political party. While in office his administrative skills were soon recognised and in 1914 he was elected Chairman of the Sanitary Committee in the town council. While he was involved in public affairs he worked tirelessly. He represented the corporation at the Royal Institute Congress at Birmingham, Folkestone and Newcastle, and his reports of these and other conferences on health matters were always interesting and instructive. He was prominent in connection with the organisation of the festivities in association with the coronation of King George V in 1911, and was in charge of the festivities at Southdale School, where the schoolchildren of the borough were entertained to tea. He was similarly active when the king and queen visited Ossett in 1912, and at the peace celebrations in 1919.

During the Great War he proved himself a useful member of the Food Control Committee, and also acted as a Special Constable from October 1914 until the force was disbanded. His duties here included night patrol, where he would have been watching for air raids, and also the important matter of distributing butter and margarine. He was also a member of the Belgian Refugee Committee. It was these and other interests in public matters which eventually led to him being elected as Mayor of Ossett in 1921.

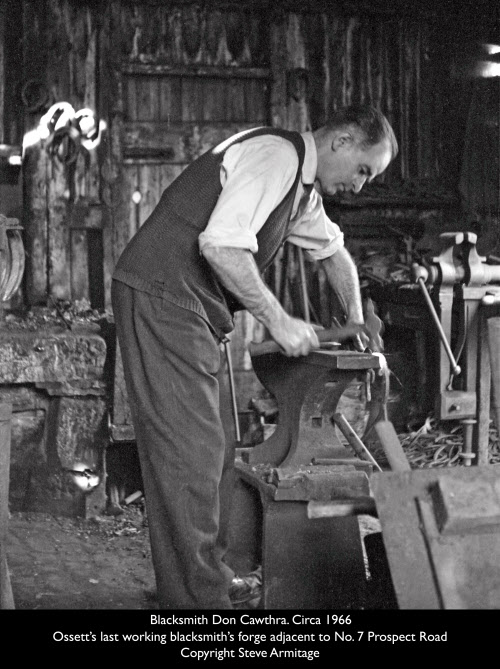

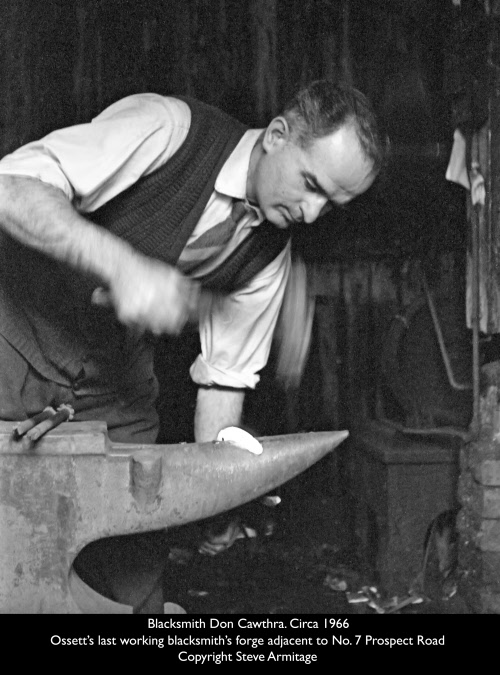

Don Cawthra had premises at 7, Prospect Road, Ossett until the late 1960s, when he moved his blacksmith’s shop to the old Spa Mill, Ossett Spa. Don was Ossett’s last working blacksmith and what follows is a short summary of his life and a few anecdotes. My thanks to Steve Armitage for the use of his photographs and for his recollections of Don.

Steve Armitage recalls:

“As young boys, my brothers and I would visit Don Cawthra’s Stithy frequently, our family home was in Brook Street off Prospect Road and but a short walk away. It was an unforgettable experience to visit this black pitch-coated timber “lean-to” building. The dark and smoky interior consisted of a forge with a coke-fuelled furnace, an anvil and various assorted tongs and irons scattered about the smoke-stained work surfaces, shafts of light coming through cracks in the timbers added to the exciting atmosphere. The right half of the building was a horse stall where the horseshoes would be trial fitted whilst still hot from the forge. My first abiding memory was the rhythm of the anvil as Don hammered and shaped red hot iron into horseshoes, “clang, clang, clang, clang, clang, clang, cla-clang”, always six single beats and the extra beat and a half!

Then there was that SMELL, like nothing I had experienced before or since, pungent, acrid smoke rose to the rafters as the red hot shoe was pressed into the horse’s hoof that was held firmly against Don’s leather apron. Once impressed into the hoof, a good and tight fit was ensured and the shoe was cooled before finally being nailed to the hoof and filed carefully to ensure there were no sharp projections. Don’s party piece (designed to impress junior onlookers) was to take a glowing coal from the furnace, drop it into his leathery hand and toss it casually from palm to palm “would THA’ like t’ave a go-a?” he always asked. No takers, but memories that have lasted a lifetime!”

Donald Cawthra was born on the 31st January 1929 and his birth was registered at Dewsbury. He was the son of miner Joseph Cawthra and Lily Hepworth who were married on the 9th October 1926 at St Barnabas Parish Church, Liversedge. Joseph, of Tanner Street Hightown, was 23 and Lily, a wire reeler of Clare Road, Cleckheaton, was aged 25. In addition to Donald the couple had another son, Stanford, who was born in June 1927. Sadly, Lily Cawthra, died in September 1938 aged only 36 years. Don was only 9 years old when his mother died. It’s not known when Joseph and his sons moved to Ossett.

Don used to live with his father Joseph Cawthra at 10 Park Street, Ossett. After his father’s death,in 1973, at the age of 69, Don moved to live in a house at the junction of Headlands and Westfield Road. The house is still there and fronts on to Headlands Road. Sometime later Don moved to Fairfield Road, Ossett, much closer to the Spa than Westfield Road, where he remained before moving to live in residential accommodation at Fitzwilliam.

He never married. When he wasn’t at his forge he could usually be found in the Royal on Bank Street. Not a man to rush home it is said that he always bought himself a couple of pints just before “chucking out time”. He was also well known locally as a featherweight boxer.

Above: Picture of Don Cawthra shoeing a horse belonging to John Myers on the right, believed to be early 1970s. The photograph shows the position of the lean to forge mentioned by Steve Armitage, with the building behind which is still there, but with the high level window blocked up. The Dewsbury & District Directory 1961 records D. Cawthra, Blacksmith, on Prospect Road in Don would then have been 32 years of age.

Alan Howe recalls Don Cawthra well:

“Don Cawthra was our smithy from the early 1980s (probably about 1982) but by then he had moved from Prospect Road to John Myers’ Spa Mills where he set up his smithy shop. The building in which he set up is still there, dating back to the 1960s or so. It was single-storey building on John’s land and fronting Spa Lane. The unremarkable building is still there and is now used as a stable. Alan’s wife Pat recalls Don visiting her pony, Brandy, a rescue, she took on in about 1982, and which the Howes kept at Haggs Hill Farm in those days.

Don came down to the farm to try to shoe him. Brandy had been knocked about a bit before we got him and he didn’t like men; even nice men like Don. He couldn’t get near him and when he did, he couldn’t shoe him at the farm. So Don’s solution, uttered in typical Don understatement was: “Get that wooden bugger dah’n to my shop afore ‘e kills somebody an a’hl rope ‘im up and sort him theer.”

In those days you did what you were told by the smithy and off we went. Don was ultimately successful, but Brandy always had to be fed treats to keep him calm on later visits. Sadly, Don had to have a leg amputated later in his life and moved from his Fairfield Road terrace home (opposite the 4th Bn KOYLI Drill Hall) into Residential accommodation. A friend of ours, sadly no longer with us, used to visit him regularly. He was a small built man, but a real character and kind at heart.”

Above: The site of Don Cawthra’s Ossett forge was inside the car “compound” adjacent to No. 7, Prospect Road, Ossett. The original line of the forge’s sloping roof can still be seen on the wall of the brick building behind the Landrover. Picture by Steve Armitage.

Alan Howe’s wife Pat recalls another Don Cawthra anecdote: