At one time, Healey was one of several individual villages that made up the larger settlement of Ossett. Over the years it has gradually been subsumed into the larger conurbation of Ossett, but Healey boasts an interesting and long-standing history dating back to Roman times and before. With its unique position adjacent to the river Calder and, later the Calder & Hebble canal, Healey soon became the industrial powerhouse of Ossett. Some of Ossett’s earliest mills were built at Healey and in turn, the area has seen large scale industrial development with William Gartside’s dye works, the Ossett Gas Company, the Healey railway marshalling yards, coal mines and sewerage farms. The industrialization of the area led to a number of houses being built for the influx of workers who came to Healey to work in the mills and the dye works.

Ancient Beginnings

The area of Heley or Healey extends roughly from the bottom of what is now Healey Road, westwards towards Earlsheaton, roughly where the Yorkshire Water Mitchell Laithes sewerage treatment farm is located. In 2007, Northern Archaeological Associates (NAA) carried out a detailed survey at Healey, specifically in the area known as “Rye Royds”, which is close to the area where the old Mitchell Laithes hospital was located. This survey revealed evidence of early settlements in this part Ossett. It is thought that the area was first settled by man because of the abundance of wildfowl and fish and also because the land was fertile enough for the cultivation of cereal crops:

The River Calder Ford at Healey

The Romans forded the River Calder at lower Healey and the route up the hill towards Runtlings was an important ancient trade and pack-horse route. The ancient road divides here to become Runtlings Lane, the pack-horse way and the drove road (Royal Road) to Wakefield1.

The Healey Ferry

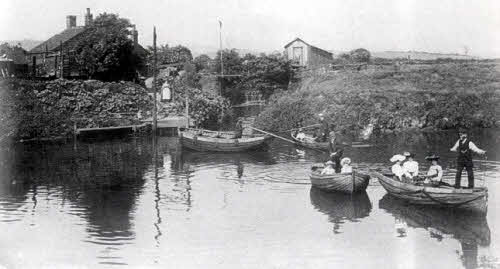

Before a footbridge was built over the river Calder in 1906, the only safe way to cross the river at Healey into Ossett was by ferryboat. The boatman shown in the picture below (dated 1905) is pulling a small boat containing three ladies across the river by means of a rope suspended between both banks. The photograph was taken from the bank of the river close to Healey New Mill.

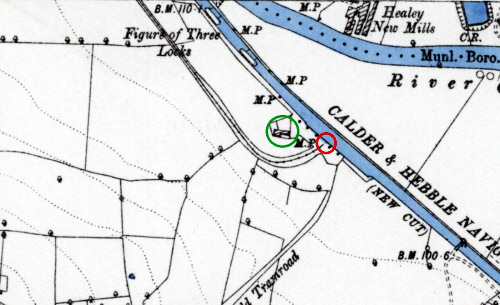

The cottage on the left of the picture is immediately adjacent the “Figure of Three” locks on the Calder & Hebble Navigation on one side and the river Calder on the other. The overflow sluice between the canal and the river can be seen to the right of the cottage. The boatman’s cottage, which is still there today, enjoyed quite extensive grounds with a fruit orchard, vegetable garden and chickens. The boatman would have been on duty every day of the week during daylight hours and may also have been required to look after the “Figure of Three” locks on the adjacent canal.

When the footbridge finally replaced the ferry in 1906, Thornhill Urban District Council built an improved bridleway as far as Lady Anne Bridge, which spans the Calder & Hebble Navigation about 200m along the canal towpath to the north-west of the cottage. This is now the main vehicular access to the old boatman’s cottage, which has been rebuilt and improved.

Not everyone used the ferry to cross the river Calder and it was noted after a fatal accident on the Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway bridge in January 1880 that by trespassing on the railway bridge, persons travelling from Thornhill to Ossett or vice-versa could save a distance upwards of two and a half miles. Consequently, the bridge was used as much by foot passengers as it was by rail traffic, despite the obvious danger. On Friday, January 9th 1880, Mark Smith aged just 15 years, the son of an overlooker at Healey New Mill was killed by a train as he crossed the railway bridge on foot. He had stepped aside out of the way of passing goods train as he crossed the tracks, but in doing so walked straight into the path of an oncoming passenger train travelling in the opposite direction. At the time, it was hoped that the accident might hasten the provision of a footbridge over the river.

Eight years later, in November 1888, the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway company proposed to apply for powers to enter into an agreement with the Thornhill Local Board, the Ossett-cum-Gawthorpe Local Board and the Calder & Hebble Navigation Company for the construction, near to Healey New Mill, of a footbridge, parallel to and to the south side of, the existing bridge carrying the main railway line over the river Calder. In the event, the footbridge wasn’t built for another eight years and it can be safely assumed that there were plenty of people who still used the railway bridge to avoid the longer walk.

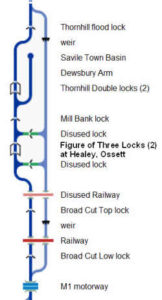

Calder & Hebble Navigation The picturesque Calder & Hebble Navigation canal runs for twenty-one predominantly rural miles from Sowerby Bridge down to Wakefield and flows through Healey, Ossett where it forms part of the boundary between Ossett and Thornhill (Dewsbury). These days, all you are likely to see are holiday makers in narrow boats enjoying the tranquility of the canal and the picturesque countryside. However, before the heyday of the Lancashire and Yorkshire railway, i.e. before about 1840, the Calder & Hebble canal was very busy with horse-drawn barges carrying cargo such as cloth, grain, potatoes and coal down to the Calder at Wakefield from as far away as Sowerby Bridge and Halifax. The mill town of Dewsbury was also served on the Calder & Hebble canal network with a tributary off the main canal at Thornhill Double Locks into Savile Town. Running for 21.5 miles between Sowerby Bridge and Wakefield, the Calder & Hebble was designed to extend navigation beyond Wakefield, where the Aire and Calder Navigation terminated at the end of the 17th Century. The waterway relies almost exclusively on the River Calder for its water.

The picturesque Calder & Hebble Navigation canal runs for twenty-one predominantly rural miles from Sowerby Bridge down to Wakefield and flows through Healey, Ossett where it forms part of the boundary between Ossett and Thornhill (Dewsbury). These days, all you are likely to see are holiday makers in narrow boats enjoying the tranquility of the canal and the picturesque countryside. However, before the heyday of the Lancashire and Yorkshire railway, i.e. before about 1840, the Calder & Hebble canal was very busy with horse-drawn barges carrying cargo such as cloth, grain, potatoes and coal down to the Calder at Wakefield from as far away as Sowerby Bridge and Halifax. The mill town of Dewsbury was also served on the Calder & Hebble canal network with a tributary off the main canal at Thornhill Double Locks into Savile Town. Running for 21.5 miles between Sowerby Bridge and Wakefield, the Calder & Hebble was designed to extend navigation beyond Wakefield, where the Aire and Calder Navigation terminated at the end of the 17th Century. The waterway relies almost exclusively on the River Calder for its water.

The “Figure of Three” locks at Healey are a little-known corner of Ossett and can be accessed only by foot from Ossett via the footbridge over the river Calder at Healey. The locks are so named because the River Calder used to bend into the shape of a figure three above Healey towards the double locks at Thornhill.

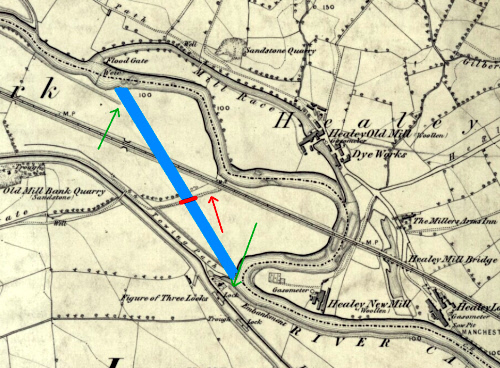

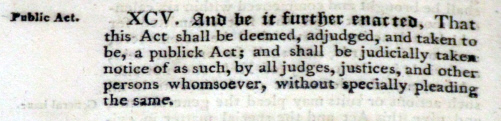

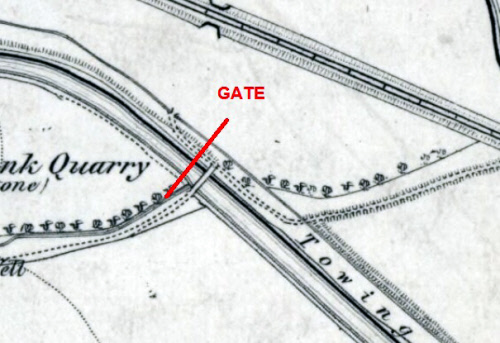

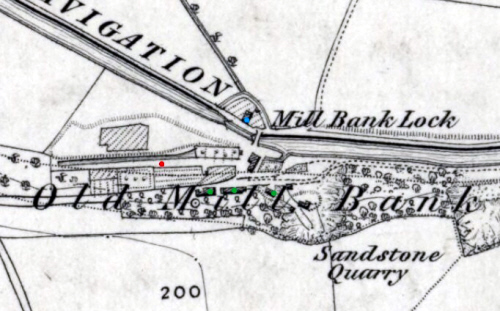

Construction started on the Calder & Hebble Navigation in November 1759 after an Act of Parliament was passed in 1758 to extend the navigation of the Calder from Wakefield to Sowerby Bridge. Civil engineer John Smeaton had been tasked with making a survey, which he did in late 1757 (see map below) and he produced a scheme which involved dredging shoals, making 5.7 miles (9.2 km) of cuts, the building of 26 locks, to overcome the rise of 178 feet (54m) between Wakefield and Halifax. Smeaton assisted by Joseph Nickalls was in charge of the construction of the Wakefield to Dewsbury section of the canal, which was built first.

By November 1794, the navigation had been completed between Wakefield and Brighouse, a distance of some 16 miles, but a large part of the Calder & Hebble Navigation near Ossett and Horbury relied on the river Calder, sometimes to disastrous effect when the river was in flood with boats often being swept away by the strong river currents. Initially, 26% of the Navigation consisted of “cuts” or canals, but eventually this rose to 68% as larger parts of the Calder were bypassed completely

The section of canal between Healey and Broad Cut lock at Calder Grove through Horbury Bridge was not built until 1838. Before then, the river Calder was used for navigation and a single lock was built at Healey to link the river Calder to a “cut” or canal for traffic going further up the Calder valley via Thornhill. This lock, which is still there in a much disused state and is shown on some O.S. maps as an “overflow” was the original “Figure of Three Lock”. The canal tow path from Mill Bank lock ended here, but the lock keeper had a small cottage and canal wharf, which can be clearly seen on the 1855 O.S. Map.

In January 1835, H.R. Palmer was asked to report following the 1834 Act of Parliament to allow improvements to the navigation up as far as Mirfield. He suggested large-scale works at the cost of £83,402, which included the construction of the “New Cut” from Healey to Horbury Bridge (and beyond) to bypass the troublesome river Calder. It is likely therefore that the double locks, which we now know as the “Figure of Three” locks at Healey were completed in 1838. The Calder & Hebble Navigation provided a vital trading link for the burgeoning woollen weaving and textile processing industry in the West Riding and may well have been part of the reason that Healey Old Mill, one of the first mechanised mills of its type in the West Riding, was constructed in the 1780s.

In its early years, the Calder & Hebble Navigation prospered, with dividends rising steadily from 5% in 1771 to a massive 13% in 1792. Under terms of the Act of Parliament, canal tolls were reduced when the dividend exceeded 10% and the first such reduction occurred in 1791. However, by 1842, it was noted that: 9

“Some two or three years ago, the shares of the Calder & Hebble Canal Navigation sold at the rate of five hundred guineas each, but since the opening of the Manchester to Leeds railway, owing to the necessary reduction in tolls, the dividends have been so much reduced that the shares now are freely offered at £180 each, that being a reduction of 70%.”

One notable feature of the locks on the Calder & Hebble Navigation and typically the “Figure of Three” locks at Healey is their restricted length. The canal is wide enough for 14ft (4.3m) boats, but the locks can only accommodate boats of a maximum length of 57ft (17m) and was designed specifically for “Yorkshire Keels”, which would fit the locks easily. The locks on the Aire & Calder canal and those on the lower part of the Calder & Hebble Navigation below Broad Cut Low locks at Calder Grove have all since been lengthened and can now accommodate boats 120ft x 17.5ft (36.5m x 5.3m).

Once the railways were widely introduced into Yorkshire, the canals became much less important, however, shareholders in the Calder & Hebble continued to receive dividends until the canal was nationalized in 1948. Most commercial traffic on the Calder and Hebble had ceased by 1955, although coal was still carried from the Yorkshire coalfields to Thornhill power station until 1981.

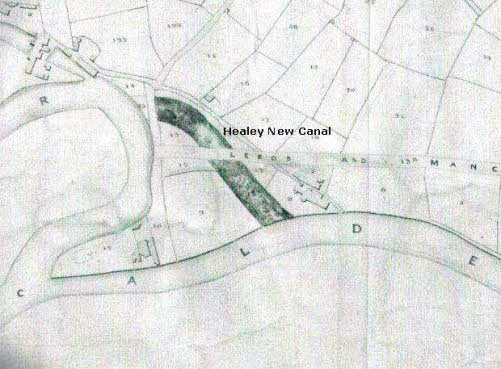

Healey New Canal

One of the lesser-known developments at Healey was the construction in the late 1830s of what is described in the 1843 Ossett Tithe Award as the “Healey New Canal” on land owned by the Manchester & Leeds Railway Company. In ten sessions of the Court of Chancery, between November 1839 and November1840, the Court considered an action by Robert Illingworth and others (the plaintiffs) v. The Manchester and Leeds Railway Company (the defendants).25 The Court summary reveals that the railway company had made excavations (i.e. the new canal) upon their own land for the purpose of diverting the River Calder and that this would cause the obstruction of a private road (i.e. the road which, even today, runs down to Healey New Mill.) The owners of Healey New Mill were also concerned that the river diversion would remove their valuable source of water from from the river and presumably, drainage back into the Calder, a reasonable claim that the railway company disputed.

Subsequently, when it was no longer needed, part of the Healey New Canal was filled in (to the north of the railway line) and by the middle 1860s, William Gartside built his dye works there (which later became Calder Vale Mill). A section of the old canal was isolated and was used as the mill dam for Calder Vale Mills. It is not known whether the Healey New Canal ever saw service with canal boats taking supplies and goods to the Healey textile mills, but this seems doubtful. My thanks to Alan Howe for the map and for much of the information about the railway bridges and the Court of Chancery action in 1840.

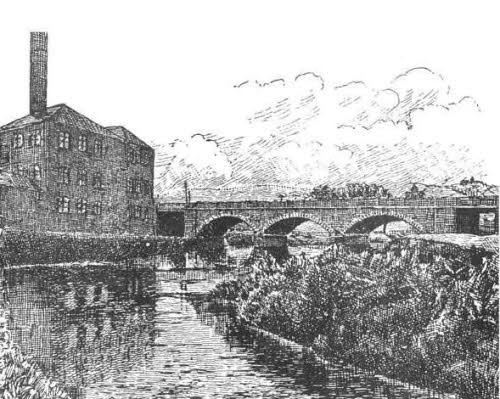

The plaintiffs were the owners of the mill and objected to the proposed river diversion for fear of the effect on their business at Healey New Mill. After a full year of hearings, the Court ruled in favour of the Manchester and Leeds Railway Company, but in the interim the railway was about to open and the Company was forced to build a temporary timber bridge to carry the railway across the Calder at the point where the present three arch railway bridge spans the river. The Company would have been relieved, for not only had they dug the channel (the New Canal), but, in March 1841 they reported expenditure of £3,000 building a five arch stone bridge to carry the railway over the proposed river diversion. That bridge was also intended to provide vehicular access to the Healey Low Mill and Healey New Mill.

There seems to have been a hiatus until November 1851, when it was reported that the railway company (now called the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway Company) announced their intention to build an embankment in place of the temporary timber bridge, the purpose of which would be to divert the river down the new canal or channel in accordance with their proposal some twelve years earlier. However, by March 1853 for some reason, the Company finally abandoned plans to divert the river and reported expenditure of £1,800 on a new three arch stone bridge to replace the timber bridge. That stone bridge is the one, which even today spans the river at Healey. But, of course, this meant that the earlier five arch bridge was now redundant and indeed it may never have seen fast-flowing water; although the O.S. map of 1905 does show a mill pond under part of this bridge and this would have been used by Gartside’s Dyeworks when this was constructed in 1867. The five arch bridge stands today at the rear of the building, which was once Calder Vale Mills (Gartside’s Dyeworks).

Manchester and Leeds Railway (later Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway)

The first twenty-seven mile section of the new Manchester and Leeds railway, between Normanton and Hebden Bridge, which passed through Healey in Ossett and Horbury Bridge, where there was a new railway station, opened on the 5th October 1840. The new railway was to revolutionise the transport system in not just Ossett, but the whole of the West Riding. However, Ossett had a part to play in the story because the opening of the railway had been delayed by the lack of a railway bridge over the river Calder at Healey due to an action Chancery Court brought by Messrs Illingworth and others at Healey Low Mill. They were objecting to a proposed diversion of the river Calder and replacement road to Healey New Mill11. The injunction, first obtained in 1839, to prevent the building of the railway bridge at Healey was dismissed in October 1840 by the Lord Chancellor who also awarded costs against the plaintiffs 12.

Left: Healey Railway Bridge, built around 1853, but subsequently doubled in width to allow additional traffic to be carried. This bridge replaced a temporary wooden bridge, which was in place when the Manchester and Leeds Railway opened between Normanton and Hebden Bridge in October 1840. It was originally thought by the railway company that construction of a permanent bridge here might be impossible because of the likelihood of flood damage to the bridge foundations with the real possibility of the bridge being washed away. The railway company planned to build an embankment here and another five-arch bridge was constructed about 1841 (behind the later Calder Vale Mills) in conjunction with a river diversion (Healey New Canal), but this was never used. Thanks to Neville Ashby for permission to use his picture.

Ossett Gas Company

Ossett Gas Company, which was located near the bottom of Healey Road was formed in 1855 under private ownership, to supply gas to Ossett and district. The original capital, according to the company’s Act of Parliament was to be £12,000; but by Provisional order in 1872, the directors were empowered to issue new shares to the amount of £35,000.

The original directors were: Mr Frank Fearnside, Mr. George Harrop, Mr George Radley, Mr James Wilson and Mr John Westerman who were all local businessmen engaged in the textile trade. The gas business was very profitable and the shareholders in the business enjoyed a dividend return for many years of 10% on £5 “A” shares and 7% on “B” shares; a very healthy and profitable return on investment. The profits and dividends enjoyed by the Ossett Gas Company coupled with the price they charged for the gas that they produced was to cause a great deal of consternation for the new Ossett Borough Council and the Horbury Local Board and it wasn’t long before the first of several municipal takeover bids were threatened.

When Mr. Edward Dews, Whinfield House, Ossett and partner in Ossett Spa Mill, a major shareholder in the Ossett Gas Company died in July 1890, a public auction was held at the Bull in Wakefield to dispose of his shareholdings and estate. There was keen competition during the bidding for the 126 Ossett Gas Company £5 “A” shares and it was noted at the time: 3

“Sixty were bought by Mr. Arthur Harrop of Ossett for £12 18s each; Mr Scott got twenty at £12 14s each. Mr. John Wray, a grocer from Horbury secured another twenty for £12 13s each. The remaining sixteen were knocked down to the same price, £12 13s each and sold to Mr. F. Dews. Ten full paid-up £5 “B” shares in the same company sold for £8 18s 6d each to Mr. Oldroyd. Mr. Jessop bought twenty more for £8 17s 6d each and twenty-six were sold to Mr. Robert Clegg, Ossett butcher at £8 17s 6d each. Mr. Briggs of South Ossett bought seventy-eight £5 shares, £3 paid for £6 each or £468 for the lot.”

Coal Gas was produced by heating locally sourced coal in huge cast-iron retorts, leaving coke as a by-product that could then be resold for domestic heating. The coal gas produced at the Ossett gasworks that was piped around the town and sold to Ossett’s ratepayers for lighting. The Ossett Local Board were the company’s biggest customers and gas was beginning to be widely used for Ossett’s new street lighting. The Horbury Local Board were also customers and clearly relations with the Ossett Gas Company in 1869 were not good, possibly because by now demand was exceeding supply. In October 1869, the Horbury Ratepayers Association decided to convene a public meeting: 4

“At one of the meetings of the Horbury Ratepayers Association it was decided to convene a public meeting on the now much-vexed gas question in the township, the reply of the Ossett Gas Company to the deputation not being considered satisfactory. Mr Quarmby occupied the chair and resolutions were passed to ask the Local Board to have the number of public gas lamps in Horbury increased to at least 100 and if the Ossett Gas Company would not supply the lamps with gas for 30 shillings per year each, to cut the supply altogether. This resolution was passed unanimously.”

In February 1872, an offer was made to the Ossett Gas Company by the united Local Boards of Ossett and Horbury to purchase the gasworks at £11 5s per share. The directors turned down the offer as not being satisfactory. This was the first of the several hostile bids by the municipal authorities to wrestle control of the Ossett Gas Works from the private owners and was the start of a bitter future battle.

By June 1872, it was clear that some sort of gas storage system was needed to help with the increasing demand. The Ossett Gas Company was advertising for tenders: 5

“To Excavators, Contractors and Builders – the directors of the Ossett Gas Company are prepared to receive tenders for the construction of a gas holder tank and valve well on their premises in Ossett.”

The Ossett Local Board agreed, in June 1874, to allow the Ossett Gas Company to erect eight terraced cottages for their workers, adjacent to the Gas Works along Healey Road and they can be seen in the centre-left of the 1985 photograph below. The cottages are still standing today.

Business is Booming

By October 1873, business was still booming and the Ossett Gas Company were making preparations for laying a new gas main from their premises on Healey Road to Gawthorpe, “in order that this remote part of the township may have a better supply of gas.”

We can get an indication of how much coal was being burned to produce gas at Ossett from this tender invitation that appeared in the “Leeds Mercury” in July 1886:

“Gasworks, Ossett – 8th July 1886

Coal Contract – the Directors of the Ossett Gas Company are prepared to receive tenders for the supply of 5,500 tons of gas coal between the 1st August 1886 and the 31st July 1887 at such times and in such quantities as the Company’s manager may direct. The quality of coal must be good, dry and free from sulphur, bats, binds, refuse and dirt.

James Castle, Secretary”

The 62nd half-yearly meeting of the Ossett Gas Company was held in August 1886 and it was noted that “there had been a slight increase in gas made at the works during the past half-year. The illuminating power of the gas had been maintained and the leakage was 11.65%.” The leakage figure seems quite high and is the only reference to gas leakage that I have been able to find.

As an indication of the salaries being paid by the Ossett Gas Company, in November 1884, the directors were advertising in the local newspapers for “a good Smith; one used to main and service laying and the inspecting of meters. Wages 27 shillings per week.”

The Ossett Gas Company continued to thrive and at the 73rd half-yearly meeting in February 1892, the Chairman’s address was very upbeat: 6

“Chairman Mr. W. Statter (the Old Hall, Snapethorpe) stated that during the past half-year there had been considerable expenditure on additional purifiers. New “cupping” had also been provided out of revenue for one of the gasholders (there were now two), which was not likely to need further doing to it for 20 years. The works were in first-class order and the consumption of gas had increased by 7% on the year. He did not know another gas company in the kingdom, which could show an equal increase. The reserve fund was at the maximum amount allowed by law and owing to the special expenditure referred to, £742 was being taken from it in order to make up the usual dividend. Resolutions were passed declaring dividends of 10% on “A” shares and 7% on “B” shares. Also re-electing Messrs. W. Statter and F. Briggs (retiring directors) and G. Richardson (auditor).”

A variety of useful by-products such as coal tar and ammoniacal liquid, which were sold off for chemical production added to the profitability of the company. An advert appeared in the “Leeds Mercury” in February 1895:

“To Tar Distillers and others – the Directors of the Ossett Gas Company are prepared to receive tenders for the purchase of the ammoniacal liquid and surplus tar produced at their Works during the next 12 months. The liquor can be loaded into tank wagons at the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway siding, Healey, Ossett. Liquor to be quoted for both Twaddel’s and Wills’ tests. Tenders to be sent in no later than 20th February 1895 – James Castle, Secretary.”

There May Be Trouble Ahead

In February 1894, a deputation from the Ossett Tradesman’s Association agreed to approach the Ossett Gas Company to ask for concessions in the price and quality of gas and also for the abolition of meter rents. The gas company subsequently refused to reduce the price of gas or make any concessions. The presiding members of Ossett Borough Council were now so exasperated with the Ossett Gas Company that they decided to convert the public street lighting from gas to electricity.

By the end of April 1895, tensions were once again rising in the town because of the high cost of gas, which was being charged by the Ossett Gas Company at 2s 9d per 1000 cubic feet. A public meeting was called at the Temperance Hall convened by the Mayor of Ossett, Alderman G.H. Wilson. The meeting was called to consider the refusal by the directors of the Ossett Gas Company to reduce the price of gas. A resolution was passed unanimously to ask for a reduction in the price of gas to 2s 6d per 1000 cu feet and to make enquiries of other towns where the gas works had been taken over by the local council. A further proposition was made to the rather moderately attended meeting that should the Ossett Gas Company fail to comply with the request to reduce the price of gas within 14 days, then the ratepayers present at the meeting should pledge themselves to cease burning gas. This was carried, but it was noted that many refrained from voting on it.

Battle lines were clearly being drawn as the dispute escalated and in July 1895, Ossett Town Council decided that a Bill should be promoted in the next session of Parliament for the Council to acquire the plant and works of the Ossett Gas Company and also to enable the council to establish electric lighting plant in the town. In the event, nothing much happened, but in June 1896 at a special meeting of Ossett Town Council, it was agreed by eight votes to five to purchase the Ossett Gas Company for a bid price of £78,840, representing 24 years purchase of the maximum dividend upon the authorised capital. The offer was once again turned down by the canny directors of the Ossett Gas Company, who really didn’t want to sell their lucrative business.

Things rapidly came to a head in 1899 as a result of a petition by the Corporation and gas ratepayers of Ossett, which was presented at the Spring Quarter Sessions held at Wakefield in April. The court ordered that the books and accounts of the Ossett Gas Company should be thoroughly audited under section 35 of the Gas Clauses Act 1837. Mr Charles Beevers, an accountant of the firm Beevers and Adjie based in Leeds was given the job and quite a job he did too, finding many irregularities and some questionable accounting practices.

Ossett Corporation and the Ossett ratepayers then made a second application to the Summer Quarter Sessions in June 1899 at Wakefield for a reduction in the price of gas charged by the Ossett Gas Company. Once again, Ossett Corporation came away disappointed because the court ruled that there was no case for the gas price to be reduced to 2s 6d per 1000 cubic feet, but some of the pain was taken away because the Gas Company were forced to pay all the costs of the court case.

Ossett Borough Council were obliged to go to Parliament with a request for a Compulsory Purchase Order. After several years of campaigning, largely led by Mr. F. Audsley. The Ossett Corporation Gas Act received Royal Assent on the 10th July 1900, but that wasn’t the end of the matter and there was one final shock for Ossett Corporation and the venerable Mr. Audsley. The Corporation had offered a sum of £85,500, a compensation value that had been determined by a jury and not by proper commercial valuation.

The bottom line was that Directors of the Gas Company were having none of it. They simply didn’t want to sell at that price and felt that £85,500 was not the true value of the asset. The directors of the Ossett Gas Company went back to the Chancery Division of the High Court in December 1900 to seek an injunction. The judge, Mr Justice Cozens Hardy eventually came down on the side of the Ossett Gas Company and judged that the Corporation were wrong and the plaintiff was right on the legal point. He held that Ossett Corporation must also pay the full costs of the action. In the event, a Mr Punchard would act as umpire with Messrs. Woodhall and Monkhouse as arbitrators to value the company. They were given until January 31st 1901 to come up with an agreed commercial valuation for the Ossett Gas Company, which would be the price that Ossett Corporation would have to pay.

How Much!

The eventual purchase price was an eye-watering £114,750, a very large sum in 1900 and equal to £9.2 million in 2008 using RPI figures22, which would have helped compensate the shareholders of the Ossett Gas Company somewhat. Because of the very high purchase price, the standard price of gas doubled, which must have been an unwelcome development for the Ossett ratepayers who had gas lighting in their houses. This had turned out to be a bit of a pyrrhic victory for Ossett Corporation and there must have been a great deal of reflection in the Council Chamber afterwards.

In 1927, Ossett Borough Council gave their verdict on the acquisition of the Ossett Gas Company as follows: 7

MODERN GAS PRODUCTION

The Corporation Gas Undertaking

In 1901 the Corporation of Ossett purchased the local gas works, which had up to that time been owned by a private company. The purchase price was a heavy one, and had the effect of more than doubling the standard charges on the undertaking. In addition, the plant was out-of-date and of insufficient maximum capacity, while the distributory system was also in pressing need of improvement. This was the formidable combination of problems, which had to be faced by Mr. Arnold E. Mottram, whom the Council appointed as engineer and manager of the newly acquired service. Mr. Mottram had gained his experience of gas engineering chiefly at the Hyde Gasworks, in Cheshire, of which he had become, assistant manager. At Ossett, there was really no alternative to a bold and drastic policy, and this was initiated and pursued with complete success. The retort house was re-constructed, the mains were practically re-laid, and not only were the maximum capacity and actual output of the works increased, but the quantity of gas produced from each ton of coal was considerably improved.

In 1913 the growing requirements of the district made it imperative that the gas works should be extended, and a scheme involving an outlay of something like £26,000 was launched. In December of the following year, the new carbonizing plant was formally opened in the presence of a large gathering. Those who attended included many gas engineers from various parts of the country, who were keenly interested in the event on technical grounds, as the manufacture of gas by vertical retorts was a comparatively recent introduction in this country. The execution of this scheme was another piece of bold forward policy, which has been fully justified by results. Under the old system of production coal was carted to the works, stacked there by manual labour, and shovelled into the retorts by hand. After the coal had been carbonized the coke had to be drawn out by hand, wheeled away by workmen, and slacked, stacked, and finally loaded into carts all by hand labour.

THE HEALEY MILLS

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, three large mills for the fulling and milling of cloth were built at Healey, close to the river Calder. Interestingly, these mills were all set up as co-operative enterprises with a large number of shareholders, drawn mainly from local clothier families, who were seeking to improve the efficiency of their individual hand-loom cloth production operations. The fulling and finishing of cloth could not easily be carried out in the weavers’ cottages that housed the bulky hand looms. Hand looms were almost universally used in Ossett during the late 18th and early 19th centuries for making broadloom cloth. By working together as a co-operative, the Ossett clothiers felt that many efficiencies could be made. In practice, there were difficulties with the co-operative approach and all the Healey mills eventually had financial problems and were sold to more enterprising individuals. Later in the 19th century, some of the more forward-thinking Ossett clothiers, who were renting space at the Healey mills, moved over to steam-operated power looms, but eventually woollen cloth weaving in Ossett gave way to the treatment of rags for the manufacture mungo and shoddy.

The first mill built circa 1787 was Healey Old Mill and it was sited close to the river so that water wheels could be used to power the mill machinery from a fast-flowing mill goit or mill race, which at Healey was strategically placed between bends in the river Calder. The other two mills; Healey Low Mill and Healey New Mill were built later between 1815 and 1830 and used steam powered machinery, perhaps with an eye on the Calder & Hebble Navigation that allowed boats to navigate the river Calder with coal for fuel and for shipping cloth to and from the mills.

William Gartside built his dyeworks at Healey and this proved to be a strategically wise decision, since cloth had to dyed to colour after it was finished in the mills located all within a few hundred yards. Gartside made a fortune before he died in 1878 and he owned vast tracts of land in Ossett, all bought with the proceeds of his successful dyeworks business. After Gartside’s premature death at the age of 62, his dyeworks became a mungo and shoddy mill and the premises were renamed as Calder Vale Mills.

There were many difficulties in Ossett during this defining period of the Industrial Revolution and the introduction of the Factories Acts in the early 1830s were to bring some of the questionable practices at Healey New Mill in particular to the forefront of the fight against child exploitation. This is covered in more detail in the sidebar to the right. Although the Healey New Mill Company in particular was identified by the Factories Inspectors in 1838 as being one of the worst cases, it seems likely that other mills in the Ossett area were equally guilty of ignoring the new Factories Act laws in respect of child workers.

Healey Old Mill First built by a co-operative of local clothiers in 1787 and one of Yorkshire’s first mechanised scribbling and fulling mills, Healey Old Mill was the first of four large mills to be built at Healey during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. The Healey Mill Company was a joint-stock business where a number of Ossett clothiers formed a company to purchase land, build and operate a mill for the scribbling and carding of their own wool; the slubbing into a yarn suitable for weaving on hand looms and then the fulling or finishing of the woven cloth. Typically, these joint stock companies, which were common in the West Riding of Yorkshire in the late 18th century, had between ten and fifty partners with company shares of £25 each. Each partner taking as many shares as he could afford.8

First built by a co-operative of local clothiers in 1787 and one of Yorkshire’s first mechanised scribbling and fulling mills, Healey Old Mill was the first of four large mills to be built at Healey during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. The Healey Mill Company was a joint-stock business where a number of Ossett clothiers formed a company to purchase land, build and operate a mill for the scribbling and carding of their own wool; the slubbing into a yarn suitable for weaving on hand looms and then the fulling or finishing of the woven cloth. Typically, these joint stock companies, which were common in the West Riding of Yorkshire in the late 18th century, had between ten and fifty partners with company shares of £25 each. Each partner taking as many shares as he could afford.8

John Emmerson was a partner in the building of Spring End Mill, Ossett, one of the first scribbling mills in the district circa 1780/81. Emmerson was a principal speaker at a meeting of clothiers held in Ossett in September 1785, where it was decided to raise a subscription to build a new fulling mill in Ossett. A further meeting of potential subscribers was held a month later, when it was decided to go ahead with the building of the mill and that shares in the new mill company should only be available to cloth makers or merchants or their families. In the event, the new Healey Mill Company was jointly financed and subsequently run by local clothiers, including members of the Ossett Mitchell, Phillips and Dews families.21

It was decided at the meeting to purchase land at Healey for the construction of two-storey, water-powered fulling mill with an attached dyehouse. The mill was to have twelve fulling stocks, powered by a waterwheel on a mill goit 814 yards long and 12 yards wide, fed from a shallow weir in the river. The design of the new works was entrusted to local civil engineer Luke Holt from Middlestown, who had gained some fame in 1776 for the surveying of Sir John Ramsden’s canal linking the Calder & Hebble Navigation at Cooper Bridge into Huddersfield. Holt was also one of two resident engineers involved in the construction of Hull Junction Dock, which was opened in 1829.

It was decided at the meeting to purchase land at Healey for the construction of two-storey, water-powered fulling mill with an attached dyehouse. The mill was to have twelve fulling stocks, powered by a waterwheel on a mill goit 814 yards long and 12 yards wide, fed from a shallow weir in the river. The design of the new works was entrusted to local civil engineer Luke Holt from Middlestown, who had gained some fame in 1776 for the surveying of Sir John Ramsden’s canal linking the Calder & Hebble Navigation at Cooper Bridge into Huddersfield. Holt was also one of two resident engineers involved in the construction of Hull Junction Dock, which was opened in 1829.

The first share offer to raise £2,200 was made in March 1786 when forty-four £50 shares were issued to local clothiers and businessmen. Eighteen of the shares were bought by seventeen Ossett investors, with the remaining shares going to investors in Wakefield (18), Horbury (2), Alverthorpe (2), Earlsheaton (2) and Dewsbury (2). Five trustees were appointed; four of them being Wakefield merchants and also Ossett woolstapler Joshua Haigh, who was also appointed as treasurer.

As the construction of the mill rapidly progressed, the initial money raised quickly ran out and it was decided to raise another £3,000 on mortgage. The trustees of the White and Coloured Cloth Halls in Leeds approved the part loan of £1,200 towards the sum required and the rest was raised elsewhere. In late 1786 or early 1787, the mill was completed and in November 1786, the company’s managing agents: John Archer junior and John Nettleton tendered for three scribbling machines and a willeying machine, which again left the company short of money and in February 1787 they had to borrow another £1,300. The mill was probably fully operational by June 1787, when a price list had been published for striped cloth, grey lists, coarse white cloth, middle cloth and coloured cloth. The scribbling business at the mill was taken over by Ebenezer Aldred of Wakefield in early 1788, whose machines were to be worked by the “South Out waterwheel.” However, the more important milling process was carried on by the proprietors Healey Mill Company. Charles Chiswick, the miller at Healey was being paid 7d a cloth for “broads” and 2d for “narrows.”

The company was managed by five trustees who were responsible for half-yearly shareholder meetings, which were held at the Star Inn, Wakefield. The first general meeting was chaired by Pemberton Milnes (1729 – 1795), JP, DL, a leading Wakefield cloth merchant, social leader, dissenter and Whig. There is some evidence that the four dominant Wakefield trustees on the management committee and who were either Unitarians or Presbyterians, may have been in conflict with the working clothier shareholders at the mill. At the general meeting in February 1787, two of the trustees, Ben Heywood and Jere Naylor, both Wakefield cloth merchants were each fined half-a-guinea for non-attendance. The one guinea fine that was levied was to be spent at the next general meeting on refreshments.

Building work was still being carried out in 1791 as the finishing off works at the mill were completed. Archer and Nettleton were still managing the mill in 1791, but in 1788 they were awarded £100 each by the trustees “In consideration of the trouble which they have had relative to the building and completion of the mill.” It was originally proposed to award them one share each in the company, but in the event, this wasn’t possible under the terms of the trust deed. However, despite the appreciation of the work done by Archer and Nettleton, the trustees made the decision to let the whole mill for a period of twenty-one years in December 1791. The previous part-tenant at the Healey mill, Ebenezer Aldred took over a small scribbling mill in Alverthorpe Road, Wakefield and took with him some of the now dated machinery. This proved to be a bad move, because he went bankrupt in 1794. The mill was let by public auction in January 1791 to a consortium of eight Ossett clothiers at an annual rental of £800 per year. This was a substantial sum in 1791 and the equivalent to £80,000 in 2009 prices using RPI as the meausre.22 This level of rent demonstrates the prosperity of the mill and the high demand for the wool processing and cloth finishing in the Ossett district. A rent of £800 per annum represented 14.5% of the total capital cost of the £5,500 required to finance the building of the mill and for the purchase of the machines. Payback would take only seven years, which was a very healthy return on shareholder investment. The dyehouse at the mill was let separately for similar lengths of time to the main mill. However, in 1812, it was used for the grinding of indigo.

The goit was doubled in width in 1791 and an additional waterwheel was installed. There was also a proposal for another goit, which was to be covered or underground in construction, but this was never followed up. The lack of water in the river Calder and increasing trade at the mill necessitated the purchase of a powerful steam engine to supplement the two water wheels. In 1803, the firm of Aydon & Elwell, Shelf Ironworks, near Bradford were contracted to supply the steam engine at a cots of £1,750 and to maintain it for a period of two years. The stone for the new engine house was quarried from the land adjoining the mill and evidence of a small quarry is still visible today. Some of the cost of the new steam engine was levied on the mill tenants who were asked to pay 7.5% interest on the capital outlay.

Ossett Mill was an important part of the West Riding cloth industry at the end of the 18th century. Of the sixty broadcloth mills in the West Riding, only Armley, Calverley and Dewsbury Old milled more cloth than Ossett and in 1796/97 Ossett Mill milled 8,274 broadcloths. So successful was the mill that in 1797, it was working day and night to keep up with the demand.8 The fourteen year lease on the mill was renewed in 1812 and was taken on by eight Ossett clothiers at a rent of £700 per annum, which is £35,000 at 2009 RPI values.22 The scarcity of water to power the waterwheels was a constant problem at the mill and it was decided that the fulling machines should take precedence to the carding and scribbling machines during times of drought.

Five years late in 1817, the mill was again put up for let, despite the fourteen year lease signed in 1812. Perhaps the high rental costs were the problem, because this time there were no takers and instead, the owners decided that they would run the mill themselves. It is likely that John Wilby was appointed mill manager in 1817 and the mill became known as “Wilby’s Mill”. He was succeeded in 1838 by his son, who later became a trustee, on a salary of £80 per annum (£63,000 a year in 2009 using inflation based on average earnings.22) Gradually, Ossett men took over as trustees in the business and by 1822 only Jere Naylor remained of the original trustees. As a consequence, half-yearly meetings were held in Ossett rather than Wakefield. In 1824 and 1825 dividends of 10% were still being paid to shareholders, which demonstrated the success of the business.

A major setback occurred in May 1829 when a fire destroyed a large part of Healey Old Mill and this report appeared in the local press:23

A major setback occurred in May 1829 when a fire destroyed a large part of Healey Old Mill and this report appeared in the local press:23

“FIRE AT OSSETT – On Monday morning about one o’clock, a fire broke out in the extensive scribbling and fulling mill of Messrs. Wilby and Co., called Healey Mill, situate at Ossett, near Wakefield. The mill we believe was not erected on the fire-proof principal and the flames in consequence of the combustible nature of the machinery and other property, raged with the utmost fury and presented an aspect appalling in the extreme. By the prompt exertions of the persons attracted to the spot, with the assistance of the Globe and the Leeds & Yorkshire fire engines, the engine house, and a new erection at the north end of the mill, were saved from the conflagration; but the remainder of the building, including a large portion of valuable property, fell prey to the conflagration and was entirely consumed. The accident is supposed to have been occasioned by a quantity of waste spontaneously taking fire. By this calamitous event, a considerable number of work-people will be thrown out of employment. We are happy to find that the property was insured to the full amount in the County, Phoenix and Atlas office.”

The loss was just over £4,000 and the insurers paid out £4,046 5s 10d in total. At a general meeting held in July 1829, it was decided that the mill should be rebuilt immediately. The trustees were clearly confident about the long-term viability of the business and they were able to pay a dividend of 5% in 1829. In 1830, two fire engines were purchased at a cost of £13 13s 5d and these were the beginnings of the “Healey Mills Fire Brigade”, which was available to other local companies and also the public, in exchange for a contribution for ongoing maintenance.24 Over the following years, the Healey Mills Fire Brigade were called upon frequently to deal with mill fires in Ossett, Dewsbury and Horbury Bridge, but was finally disbanded in 1891 as local boroughs like Ossett introduced their own fire brigades.

From 1839, to comply with the new requirements of the Factories Acts, a doctor was paid for to sign children’s’ certificates and the Mill Feast bills were paid from the year 1841/42. The mill enjoyed its period of greatest prosperity in the mid-1840s, with dividends of 30% being paid in two consecutive years. Like the other two mills at Healey, Healey Old Mill had its own gasworks and gasholder, which were built circa 1844/45 and any surplus gas was sold. The company also did a little bit of farming on the pasture land around the mill and in 1838/39, a profit of £80 was made on cows bought for feeding up. Spinning mules to produce yarn were introduced at the mill in 1840, bit otherwise very little changed for many years.

The dyehouse at the mill, although owned by the company had always been rented out to tenants and William Gartside was probably a tenant rather than the owner. By the late 1870s, the Healey Old Mill directors had decided to sell the dyehouse, as this advertisement in the “Leeds Mercury” dated 10th August 1878 shows:

“To be sold by private contract, the dyehouse at Healey Old Mill, Ossett lately occupied by the late William Gartside, containing ten indigo vats, two dye pans, scouring appliances, etc. together with a close of land adjoining containing, and including the site of the buildings, about 4,400 square yards more or less. The property abuts on to the river Calder and the water mains of the Ossett Local Board pass along the front.”

From 1870, income from slubbing and spinning for the first time exceeded income from milling and in the last full-year of the company operation, milling income had dropped to less than £1,000. The mill was still geared very much to the rapidly declining hand-loom industry and the end was now close. The amount owing to the bank had risen from £100 in 1865 to £3,000 by 1876. To emphasize the decline in the mill’s fortunes, in 1876, there was little interest in bidding at a public auction when one of the mill shares was offered.

In 1877, the entire mill was let to Ossett woollen manufacturer, Walter Berry who had a new building erected in 1877 at a cost of £1,850. The new building was designed by Ossett architect, S.H. Kendall, who was also a schoolmaster at Ossett Grammar School. For safety reasons, the height of the mill chimney was reduced by one quarter in 1883; it had been out of perpendicular since it was built by Ossett masons, Goodacre and Dews.

The rental income from Walter Berry reduced the deficit owing to the bank from £2,745 in 1875/76 to just £5 in 1881/82, rising to a credit balance of £1,315 in 1886/87. Berry continued for about ten years, probably with scribbling, spinning and fulling, which helped put the mill back into a healthy financial state and in 1882, the mill directors were awarded £50 each for their good work over the previous five years. However, everything changed in 1887 with the arrival of of a new tenant, J.J. Mitchell who spent £3,000 installing power looms and shafting, making Healey Old Mill a power loom mill, like many others in the district. This turned out to be a retrograde move in some respects because rental income dropped from £1,391 in 1886/87 to below £775 with a corresponding reduction in dividends from 20% to 10% plus an unwelcome bank deficit of £1,305, which dropped to £540 when the Healey Old Mill Company was finally wound up.

The mill was purchased in 1892 by John William Smith, manufacturer of mungos and shoddies and his company John William Smith Ltd., occupied Healey Old Mill from 1892/93 up to the 1920s. The business was formed into a limited company in 1904. Smith had started in the mungo and shoddy business in Ossett with Eli Townend in 1871, but after the break up of their partnership in 1883, Smith leased room and power from J.S. Fawcett (and others), the owners of Calder Vale Mills, which were previously William Gartside’s Healey Dye Works.

John William Smith Ltd., were principally the makers of pulled and carded shoddy and their specialty cloths were made of all shades of dyed merino, serge, and worsted materials. The principal part of their trade was export, which was done indirectly through Bradford merchants, also Messrs. John William Smith, Ltd. Smiths’ also did commission carbonizing, dyeing, pulling and carding. John William Smith lived a short distance from Healey Old Mill in the impressive “Green Lea” just up the hill on Healey Road before he died at the end of 1915.

Healey Low Mill

Another early Ossett scribbling and fulling mill, which dates from the early 19th century and was probably built circa 1815. Healey Low Mill was owned in 1819 by James Briggs and in 1834 by Samuel Ellis and Company. The mill was sited right on the bank of the River Calder at Healey before the river was diverted when the railway marshalling yard was constructed in the early 1960s. Like other mills erected at that time, the buildings were low, machines were close together and working space was tight. In the early twentieth century, it had sixteen carding machines, but the space between them was so small that workmen had difficulty in cleaning them. The mill continued in use until 1930.

Like the other mills at Healey, child labour and consequently child deaths were not uncommon in the early to mid-19th century. However, why a three-year old boy should die so horribly at Healey New Mill can only be imagined? The “Leeds Mercury” for September 10th, 1862 tells the tragic story:

“At an inquest held at the Millers’ Arms Inn, Ossett, on view of the body of a boy aged three years, named Dan Moss, who came to his death by injuries received in falling into a cistern of steam water, at the Healey Low Mill, Ossett on Saturday evening. The jury in this instance returned a verdict of accidentally scalded.”

In May 1870, the “Leeds Mercury” had an advertisement offering Healey Low Mill for let, which gives us an indication of the extent of the mill operation:

“TO LET, the HEALEY LOW MILL, situate at Ossett, either whole or in part, with immediate possession, consisting of three 5ft. condensers, five 4ft. condensers, two pair of self-acting mules, 984 spindles; four pair of hand mules, 1,020 spindles; one horse, 100 spindles with scribblers and carder; one shake willey, one tenter-hook willey, six pair of stocks, five milling machines, two washing machines, one driver and one wringer; together with six cottages and six acres of land. For further particulars, apply at the Mill.”

In 1954, Healey Low Mill, by now in a dilapidated state, was taken over by Ossett building company, Harlow & Milner who repaired it and made it good. They then manufactured gypsum plasterboard at the mill for several years. Healey Low Mill was demolished circa 1960 to make way for the extensive British Railways Marshalling Yard that extended right over to Storr’s Hill Road. Work began on the new British Railways Healey Mills marshalling yard in 1959 and included the diversion of 1,030 yards of the river Calder into a new channel to the south to clear space for the site. The new river cut was completed in November 1960, but a disastrous flood eroded the banks of the new river channel and the entire site was badly flooded. Other works included the filling in of the old mill dam at Calder Vale Mills and the transfer of the fish to a short stretch of the old river channel, which was retained and used by the Ossett Angling Club (now part of Wakefield Angling Club) and is known as Healey Dam. The access road to Healey New Mill was also diverted as well as the removal of Ossett Sewerage Works at Healey.

Healey New Mill

Built in 1826-27 as a steam-powered scribbling and fulling mill by established Ossett clothier, Benjamin Hallas. After Hallas went bankrupt in 1830/31, the mill was sold first in 1833 to Ossett maltster Joshua Whitaker and then leased to a partnership of up to thirty-three local clothiers who ran it as the “Healey New Mill Company. The original mill is built of stone and brick, and is of three storeys with an engine house between the main working part (eight bays) and a two bay narrower end perhaps used for warehousing. The mill is of fireproof construction with cast-iron beam and joist and a stone-flagged floor. Minor buildings included a dyehouse and a single-storey heated cloth dryhouse. After 1881 the mill was mainly used for the manufacture of shoddy and mungo, and a rag warehouse and a rag-grinding shed were built.

An original list 15 of the Healey New Mill Company partners between 1835 – 1839 reveals many well-known old Ossett names:

In January 1836, a deed of settlement was signed relating to co-partnership between twenty-seven of the working partners listed above, to agree to carry on business as scribblers, carders, spinners of wool, fullers of cloth at the mill. There were to be 81 shares in the business, presumably with each working partner holding at least one share. The new co-operative business was to be managed by a Committee of Management and would be called the “Healey New Mill Company”. This idealistic concept, however well-meaning was sadly doomed to failure since not unexpectedly, some of the better-run businesses did well and others failed.

By 1860, several of the original partners had moved on to build their own mills, for example John Wilson, who subsequently died in 1851. Some of the original partners or their replacements were struggling or had gone bankrupt. For example, James Ellis and Joseph Emmerson were both bankrupt by 1838. However, in 1862, the mill was in the ownership of Ossett clothier Benjamin Wilson and Company, who was in business with his son Robert Wilson, until Robert died in 1878. Wilson maintained the co-operative with the other clothiers and there were now 117 shares in the business. However, the business was not in good financial shape and when George Harrop, Horbury clothier bought one of the shares, he had to pay £29 18s 9d, which was his part of the outstanding bank debt of £3,503 2s 9d that had been owing since 1843. The Wakefield and Barnsley Union Bank forced the owners of Healey New Mill to surrender the deeds of the mill against debt of £6,381 16s 0d, which had built up because some of the partners hadn’t paid their rents,or had gone bankrupt, despite some very good trading years in the 1860s.

The report of the Rivers Pollution Committee of 1871, which was published in 1873, noted that the Healey New Mill Company of Fullers, Millers and Scribblers employ fifteen staff. The company was scribbling and fulling 360 tons of goods per annum to a value of £20,000. It was noted that the mill was steam powered with a 32 horse-power engine and that no dyes or bleaches were used at the mill.

On the 11th February 1879, the Wakefield and Barnsley Union Bank gave notice the managers of the Healey New Mill Company( at that time Robert Illingworth and George Nettleton) to the effect that they required payment of the outstanding debt of £6381 16s 0d plus accrued interest, a sum of over £7,900, otherwise they would put the mill up for sale. Clearly, the co-operative was struggling and the local press carried a notice, which asked the creditors of the Healey New Mill Company to send in their claims by the 15th July 1879. The company was eventually wound up in 1880 after a Court of the Chancery petition by Benjamin Wilson and George Harrop. The Chancery Court ruling was that the heavy debt liability built up over the years had to be shared between the Company’s shareholders16 much to the relief of Benjamin Wilson, who at 82 years of age was now close to death and keen to leave the bulk of his estate to his surviving children. Wilson died on the 15th April 1881, just before Healey New Mill was sold at auction.

The Healey New Mill was offered for sale at auction in February 188117 as follows:

“1. All that valuable three-storeyed mill called Healey New Mill with land of 2 acres, 3 roods and 28 perches, together with cottages, dyehouse, warehouse, engine and all fixed machinery.

2. All the unfixed machinery, consisting of scribblers, carders, condensers and other machinery.

Stewart & Sons, Solicitors, Wakefield and Haigh, Barker & Barker, Solicitors, Horbury Bridge.”

One of the tenants at Healey New Mill was David Giggal, a wool extractor and he bought the mill and the machinery at a public auction held on the 28th April 1881 for £6,200. However, it was noted that just a month before the auction that one of his rag machines at the mill worth £50 had been destroyed by fire.18 David Giggal was one of the Ossett industrialists who had moved away from weaving cloth using power looms into the manufacture of shoddy (and later mungo) and this was to become the dominant textile industry in Ossett. In 1885, Giggal entered into a partnership with his brother-in-law, Edward Clay at Healey New Mill, but the partnership only lasted twelve years because David Giggal died in 1897.19 The company carried on as a limited company after Giggal’s death and Giggal & Clay Ltd. was set up in 1898 with capital of £10,000 in £10 shares to take over Healey New Mill.20 However, by 1901, Kelly’s Directory shows that Giggal & Clay Ltd had become a branch of the Extract Wool and Merino Company Limited, but were still trading at Healey New Mill, but had sold some of their land to the Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway Company. By 1905, Healey New Mills was disused and Edward Clay was in business as Edward Clay & Sons in Wesley Street, Ossett.

It isn’t known how long the mill was disused, but by 1914 it was being used for leather dressing and 1919 the Extract Wool and Merino Company sold the premises to John Thomas Townend for £3,000, suggesting that the mill was in decay. Townsend subsequently let the mill, described as having mungo and shoddy machinery, to the Langley Brothers, who had premises in Dale Street, Ossett. Finally, in 1929, John Townsend, described as a mungo manufacturer sold Healey New Mills to Wilson Briggs and Norman Briggs, Ossett rag merchants for just £1,000.

Healey New Mill is still in the ownership of Wilson Briggs & Sons and is currently used, in 2010, as an industrial business park providing lock-up premises for small firms specialising in things such as car bodyshop repairs, metalwork manufacture, brick manufacturing, sports equipment manufacture, electrical services and even a shop selling pine furniture.

The mill building, which is now Grade II listed is built from coursed squared rubble (north and east elevations) and brick (south and west elevations) with stone slate roofs. There are three storeys and an attic. The main building is an eight-bay construction facing north-south with a single-bay engine house to the south and a further two bays, less wide, further south.8

Calder Vale Mills and Healey Dye Works

William Gartside’s extensive Dye Works were built in 1864 on the site of the Healey New Canal, which was partly filled in by the late 1850s. Part of the old canal was then used by the dyeworks and later Calder Vale Mill, as the dyeworks were to become, as a mill dam which can be clearly seen on the 1938 O.S. map shown above.

In 1867, there was a disastrous fire at the works and the “Lancaster Gazette” dated 29th June 1867 had this story about the blaze, which gives some indication of the organic materials that were used by Gartside’s company to dye cloth rather than chemicals, which became the norm later:

“On Saturday morning, about one o’clock, a fire broke out in the est end of a pile of new buildings, the property of William Gartside, dyer, Healey, Ossett. The building was quickly enveloped in flames, their being a large quantity of logwood, fustic, saunderwood, various red woods, myrabolam nuts, and other valuable dye wares, stored there. The fire was discovered by a widow woman living near to the premises. Ellis Brothers’ and the Healey Old Mill Company’s fire brigades arrived at the conflagration about half-an-hour after the discovery, and having plenty of hose and a good supply of water at hand, they played upon it very effectively, but were unable to save any large portion of the building from the flames, for in less than an hour after the alarm was given, the roof fell in with a loud crash. The efforts of the firemen were then directed to saving the engine and shafting, and large piles of dye woods in close proximity to the building outside.; these were nearly all rescued. Mr. Gartside had caused 50 tons of dyewares to be removed from the compartment only a week previous, otherwise the damage would have been much greater. There was a good deal of new machinery in the building, but by the judicious management and forethought of Richard Johnson, the engineman, it was preserved almost entirely from damage. The flames were extinguished about half past three o’clock and the fire was finally put out by nine o’clock. Mr. Gartside estimates the damage at £1,500 or £1,600 and he is only partially insured in the Liverpool, London and Globe office. It is not ascertained how the fire originated, but it is supposed that the dye wood, which had been ground to powder and stored to heaps in the chamber, ignited spontaneously.”

Gartside, came from a family of dyers who, it is thought, moved to Ossett from the Huddersfield area in the late 1700s. Gartside was unmarried and after his death on the 22nd November 1876 at the age of 62, his extensive estate of land in Ossett was kept largely intact until it was auctioned off in 1902. However, the Healey Dye Works, which in 1876 was employing 60 local men was sold to the firm Fielding & Co. whose principal was James O. Fielding who had come to Ossett from the Sowerby Bridge area. Fielding committed suicide in 1879.13

“The body of James O. Fielding, of the firm Fielding & Co. Healey Dyeworks, Ossett, was found in the river Calder yesterday afternoon. The deceased went to his works soon after nine o’clock yesterday morning in a cab and after speaking with a book-keeper in his counting house, left at ten o’clock and was seen going in the direction of the store in which the dyewares are kept, a few yards from the river bank. He was not seen again alive, as far as it present known. About two o’clock, a man saw his body, which was partly immersed in the river Calder, not far from the bank, about a quarter of a mile lower down the river than the spot where the works are situated and not far from Horbury Bridge. His watch had stopped about noon. It is thought that he might have been walking by the river side to Messrs. Harrop’s Albion Mill, Horbury Bridge and have fallen into the water whilst in a fit.

He was 35 years of age and formerly carried on business at Sowerby Bridge, but came to Ossett eight months ago to take the business carried on for many years by the late Mr. William Gartside. He was unmarried and is stated to have been somewhat ailing in health lately. Last week the deceased was presented with a testimonial from the congregation of the Independent Chapel at Sowerby Bridge, with which he used to be connected. The body was removed to his late residence to await an inquest.”

In 1883, the dyeworks were sold to the firm Fawcett, Firth and Jessoop.14 The mill must have been leased to Walter Berry, because by June 1887, Berry was auctioning “the valuable woollen machinery and effects equal to new” at Calder Vale Mills after buying outright Westfield Mill in Ossett, which already had mill machinery.26 However, like the other mills at Healey, accidents to the workers at Calder Vale Mills were common and this account of the death of 17 year-old John William Butterworth gives us an insight into the way the mill was run in 1887: 27

“SERIOUS ACCIDENT TO MILL OPERATIVE AT OSSETT – Early yesterday morning, an accident occurred at Calder Vale Mills, Healey, Ossett by which a young man named John William Butterworth, aged 17, sustained a compound fracture of the skull and other injuries. Butterworth was employed as a layer-on in the rag-pulling department, the machines in which had been running through the night. He went to his work shortly before six, when the engineman shut off the steam in order to allow the machinery to be oiled ready for the day. No person appears to have seen the accident, but it is supposed that Butterworth was adjusting a bolt on a drum, near to which two other workmen found him lying in an insensible condition. He was taken to his father’s house in Bank Street and died in the afternoon.”

This story began in January 2016 with the discovery of an old newspaper cutting making reference to one of the Healey lads, Herbert Smith Vickers, who was killed on the first day of the Battle of The Somme, 1st July 1916, in WW1. The report made reference to Herbert’s father, Henry Vickers, being involved in the building of the Healey Mission as a memorial to his son and the other Healey lads who died in WW1. – Alan Howe, April 2016.

The press report continued in the following vein. In July 1970 the Healey Mission room, built as a war memorial to the fallen soldiers from Healey, celebrated its golden jubilee. One of the oldest stalwarts, Alice Vickers, was known as the ‘Queen of Healey’. Her father, Henry, was one of the main workers when the mission was built in 1920. Miss Vickers had her brother’s medals and commemorative certificate framed and hung in the church for the jubilee service. The church was so well attended for the jubilee service, in 1970, that some of the people had to stand in the church hall.

This chapter of Healey’s history looks firstly at the Vickers family, secondly at King’s Yard and other dwellings situated in Lower Healey.

The Queen of Healey – Alice Vickers and her family of King’s Yard, Healey

Alice Vickers, the Queen of Healey, was the younger child and only daughter of Henry Vickers and his wife, Mary Hannah (nee Beaumont). Alice was born on the 2nd May 1900 and baptised at South Ossett Christ Church on the 27th June 1900. Her parents, Henry and Mary Hannah (Beaumont) had married in the same church on the 14th October 1893 and their first child, and their only son, Herbert, was born on 1st April 1894. In 1901, when Alice was just 10 months old, the family lived on King’s Row, Healey, a terrace of seven or eight dwellings comprising 2,3 & 4 room accommodation, which provided homes for workers from the nearby dyeworks, mills, fellmongers and quarries. Their neighbours in 1901 included the families of Brook, Talbot, Gawthorpe (2 families), Richmond and White. At some stage, Alice Vickers was a Sunday School Mission teacher at the Mission Rooms.

Alice’s father, Henry, was no stranger to this patch of Healey. He was the son of John Vickers and Elizabeth Stawman who married in Spring 1859. Henry was born on the 1st November 1870 and was baptised at South Ossett Christ Church on the 28th May 1871. In that same year young Henry, aged 5 months, was living with his parents, three siblings and three cousins (surname Ellison) in one of two dwellings described on the Census as “Flatts Healey”. Their neighbour was widow Agnes Audsley, with her three children and a lodger. The dwelling in which they lived was to the east of the path that leads from Runtlings (Runtings) Lane to Healey. The next address on the 1871 census was Mitchell Laithes before the Census Enumerator made his way to Pildacre for the rest of his count.

By 1881, and in 1891, the Vickers family had moved a short distance to a dwelling in lower Healey, which was almost certainly King’s Yard, although the census merely recorded it to be “Healey”. By 1901, as we have seen, the Vickers’ address was King’s Row. The address, no doubt, took its name because it was immediately to the rear of The Miller’s Arms public house. This was owned by John King from 1881 and by William King from 1889 until the public house was acquired by The Bentley Brewery Co. Ltd.

In 1898, John Vickers, Alice’s grandfather, appears to found himself in a bit of trouble with some money lenders. On the 19th March 1898, John, aged 68, was committed to Her Majesty’s Prison at Wakefield for an unpaid civil debt. The record is silent as to whether John paid up his 25s 6d (£1.27p) or served his sentence, but if he did fail to pay, he would have been imprisoned for 14 days. The record does, however, tell us that John was 5’3” tall with grey hair, bald on the top of his head and a labourer. He had no previous offences. John and his wife were still living at lower Healey, probably in King’s Yard or thereabouts in 1901 and John most probably died there in August 1902, aged 72 years. He was buried at South Ossett Christ Church on the 30 August 1902. John Vickers was living on Storrs Hill in 1861, but by 1871 he and his wife and children were in one of only two dwellings called Healey Flatts, in lower Healey. John Vickers, grandfather of Alice, had lived in the same Healey community for more than 30 years and, when he died in 1902, he was but ten steps away from his son, daughter-in-law and grandchildren.

It mattered little to the Vickers family that in 1911 the census enumerator recorded them at 43, Gas Works Row because when Henry Vickers completed his Census Return he indicated that he was living at 43, King’s Buildings. Independent thinkers and firm of mind were the residents of lower Healey. It is safe to assume that the family were occupying the same 3 roomed house that they occupied 10 years earlier.

The Vickers family of four, became just three on 1st July 1916 when Henry and Elizabeth Vickers lost their only son, Herbert Smith Vickers who was killed in action on the first day of the Battle of the Somme in WW1. Herbert, of 43, Healey Road, was one of 19 young men with a Healey address who were killed during the conflict. Of those men who died in 1914-18, six came from the close community of lower Healey.

By 1927, King’s Row or King’s Buildings or King’s Yard or Gasworks Row or, just plain, Healey or Healey Road had changed its name once again. Alice’s father, Henry of 43 Gasworks New Row, Healey, Ossett, died, aged 57 years, on the 13th September 1927, when administration of his £176 estate was granted to his widow, Mary Hannah. Henry Vickers was born and died at lower Healey. In 1939, Alice, a rag sorter, was living at 43 Gas Works Row with Alice’s uncle and aunt, Joe Beaumont, and his wife or sister, who were both in their 70s.

There is no record of Alice’s mother, Mary Hannah, in 1939, but In early 1961, a local woman named Mary Hannah Vickers died, aged 84 years. In any event, Alice, a spinster aged 61 years, was the last of this Vickers line and in 1961 she was one of only two residents living at King’s Yard. Alice was living at 43, King’s Yard, the place of her birth in 1900.

Alice Vickers died in Summer 1983, aged 83 years. By this time it is believed that the remaining King’s Yard dwellings may have been demolished and that Alice may have moved further up Healey Road to live out her later years in a dwelling almost opposite to the Healey Mission. This was the building that her father, Henry, helped to build in 1920 as a tribute to his son and Alice’s only brother, Herbert, who lost his life in WW1.

Alice Vickers’ death in 1983 brought to an end the Vickers family presence, at least 110 years, at Lower Healey. Her grandfather, John, a mill labourer, had moved here before 1871 and she and her father, Henry, a foreman in a rag warehouse, were born in Healey and lived here for the whole of their lives. Alice Vickers might have been a humble rag sorter but she was truly “The Queen of Healey.”

Healey – King’s Yard, Low Mill Road, Calder Terrace, Millers Arms, Calder Vale Mill (Formerly Gartside Dyeworks), Calder Vale Terrace, Old Mill Yard, New Mill Yard and Healey Flatts.

These are the locations which provide the focus of this part of the history of the people of Healey, and their homes during the 19th and 20th Centuries. The history does not include dwellings built further up Healey Road (Lane) beyond the Healey Mission built in 1920.

The history of Healey, like Flushdyke, is the story of a lost village on the fringes of Ossett, but it has a long and industrious history. This section looks at the dwellings and at the people of Healey from the early 19th century set in the context of the nearby mills: Healey Old Mill (built 1787), Healey Low Mill (circa 1815), Healey New Mill (1826), and the Calder Vale Dyeworks (1864) on Low Mill Road. The history of these mills has been explored elsewhere, including, in expert fashion, on this website and, of course, they are integral to the history of Healey’s residents over the years. Without the Mills the people would not have been in Healey.

However the Mills would be nothing without the people who worked them day in and day out for most of their lives. The history of Healey’s people, their homes, their families and their work has never been told, until now.

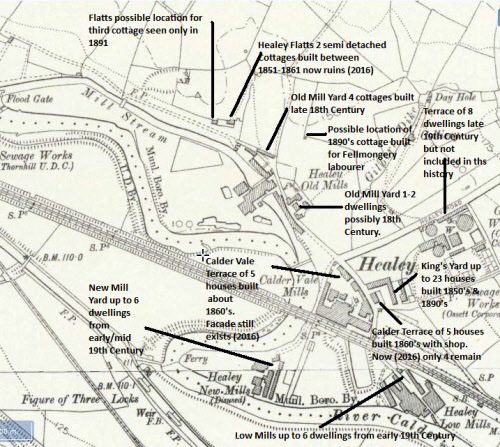

The first of the Healey Mills to be built, in 1787-1791, became known as Healey Old Mill. It stood on the site, which became the business premises of Matthews Foods in 1964, until 2005 when the Company was purchased by Kerry Foods, who remain here at the time of writing (February 2016). Even at this early 18th Century date it is probable that the Healey Mill Company provided some dwellings for their workers. The evidence suggests that there were between four and six Dwellings dating from this time and that they survived, in the Old Mill Yard, at least until the 1960s.

The second Healey Mill to be built was Healey Low Mill in 1816 and this was followed some 10 years later when Healey New Mill was constructed in about 1826. Over the years each of these Mills provided accommodation for their workers. In these early years most of the homes were “one up one down” but occasionally three roomed homes were seen, comprising one downstairs room and two bedrooms.

By the mid 1820s it is likely that there were 12 dwellings at the Old Mill and Low Mill and in 1841, by which time the Healey New Mill had also been built, there were 19 dwellings and 105 residents. 12 of these homes were in the Old and New Mill Yards and 7 in Low Mill Yard. The six in Old Mill Yard were located on the north side of the Mill with a stone built terrace of four standing at the bottom of the footpath that led to Runtlings Lane. All six dwellings here were still occupied in 1961. The 1851 census shows little change except that the Millers Arms Public House had been built.

By 1861, there had been significant changes as the dwellings increased from 18 to 31 with 158 occupants. The additional housing stock had, in the main, been built to the east of the Millers Arms, mainly in the Yard behind and adjacent to the Millers. This included Calder Terrace, five dwellings including one with a grocer’s shop. This Terrace still stands today (2016) albeit with only four houses but including one with a shop front. To the west of Old Mill two stone built semi detached cottages had been built at Healey Flatts. These too were still occupied in 1961, but now only the ruins of these remain.

In 1864, the fourth Healey Mill, William Gartside’s Dyeworks (later Calder Vale Mills), was built and by 1871 the number of dwellings was 35 (1861 -31 dwellings), providing homes for 136 adults and children. The increase can be ascribed to the construction of Calder Vale Terrace of five dwellings almost directly opposite the Millers Arms . The first floor facade of this terrace of 3 and 4 roomed dwellings can still be seen in 2016 with the number 10 above the entrance door to the house closest to the Millers.

In overall terms little had changed by 1881, with now 33 dwellings, but an increased population, which reached 174 occupants; an average of about five people per dwelling. After 40 years of landlords called Gawthorpe the Millers Arms landlord was John Duffin. The decade starting from 1880 also saw significant development, so that by 1891 there were 44 dwellings, which was mainly due to the building of a second terrace of 7 or 8 dwellings in the yard behind the Millers Arms. These were probably built in the early 1880s to mirror a similar terrace built there in the 1850s or early 1860s.