This is the story of the Kitchen family of Netherton and Horbury during the second half of the 19th Century and the turmoil of the war years in the early 20th Century.

At the end of the 19th Century the family had eight surviving sons and two daughters who had been born to miner Richard Kitchen, from Welby, Lincolnshire, and his Netherton wife Charlotte (nee Schofield), born in 1860, who married in 1881.In her lifetime Charlotte gave birth to twelve children, two of whom, twins Joseph and Richard, were born and died in 1907. Another two children, John Henry and Edith, died in 1906 and 1908 respectively. How utterly dreadful must have been the years 1906-1908 when Charlotte, in her mid/late 40’s, gave birth to two and buried four of her children. Charlotte could bear it no more and she died in summer 1911, aged 50 years.

By 1911 the family comprised eight surviving children, seven of whom were sons born between 1884 and 1902. Five of those sons were of an age when it might be expected that they would serve their country and go to war. At least two of those sons, Thomas and George, were lost in The Great War.

The sons of Richard and Charlotte Kitchen were John Henry (1882 – 1906), Thomas (Tom) (1884- 1916), Fred (1886 – 1967), George (1889 – 1917), Willie (1893 – 1964), Ernest (1898 -1952), Herbert (1900 – 1978) and Harry (1902-1980). The daughters were Edith (1891 – 1908) & Mary Elizabeth (1895 – 1972).

Two of the sons lost their lives in The Great War;-

Thomas (Tom) Kitchen who was baptised on 26th December 1884 at St. Andrews Church Netherton in the Parish of St. Luke and became the eldest son in the family following John Henry’s death in 1906. Tom Kitchen who served with the 7th battalion Lincolnshire Regiment died of his wounds on 5th July 1916. He was 22 years of age.

George Kitchen who was born on 10th March 1889 and baptised at the Netherton Wesleyan Methodist Chapel on 28th May 1889. Lance Corporal George Kitchen who served with 6th battalion King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry was killed in action on 16th December 1917. He was 27 years of age.

Two other sons, Fred and Willie, served and survived in The Great War.

We will see more of these sons later in this biography but first something about their lives and whereabouts before August 1914 when war was declared.

Life in peacetime 1870-1913.

The story begins when Richard Kitchen, born in Welby near Grantham, Lincolnshire on 18th March 1858 set out to find work. He moved north to Yorkshire from Lincolnshire in the late 1870’s and by spring 1881, Richard aged 22 years was lodging with the Schofield family (note the name) at Beatson’s Row, Netherton. On 26th December 1881 Richard Kitchen, a 23 year old miner, married Charlotte Schofield, aged 21; both were living at Netherton at the time of their marriage which was made at Thornhill Parish Church. Richard’s father, also named Richard, was described as a farmer(deceased); Charlotte’s father’s name did not appear on the marriage registration but her mother was Mary Schofield, aged 18, of Hostingley Lane. Charlotte was born in summer 1860 and baptised at Thornhill St. Michael’s on 19th August 1860.

Welby Village, Lincolnshire once home to Richard Kitchen

How Charlotte must have dreamed of a life of normality as she tucked away what appears to have been her earlier dysfunctional existence. Charlotte Schofield was 20 years old when she married Richard Kitchen at Christmas 1881. Her father unknown, she was the illegitimate child of Mary Schofield who was born in 1843. Mary Schofield herself was also illegitimate; she was the daughter of Charlotte Schofield born in 1820 to George and Mary Schofield (nee Parkin) of Sandy Lane. The elder Charlotte Schofield (born 1820) married James Jowitt in 1847 and the illegitimate Mary Schofield lived in the Jowitt household in 1851 and also in 1861 by which time her own illegitimate daughter, Charlotte, had been born. She too lived in the Jowitt household.

There follows an aside regarding Charlotte Kitchen’s earlier life;

Charlotte’s mother, Mary Schofield of Hostingley Lane born in spring 1842, married Robert Brook(e), a collier of Edge End at Thornhill Parish Church on 15th December 1863. Both made their mark on the marriage registration. In 1871 Robert and Mary Brook were living on Hostingley Lane, near Smithy Brook with their four children. Also living in the household was 10 year old Charlotte Schofield whose name on the Census was Charlotte Brook.. Their closest neighbours were Joseph Jowitt and his wife, Charlotte (nee Schofield) born 1820, who was the grandmother of Charlotte Schofield (born 1860).

Later on 27th September 1871, Robert Brook a collier working at Captain Joshua Cunliffe Ingham’s Hostingley Lane pit was killed in an explosion of gas in the mine which killed him and another man. An Inquest was held at The Saville Arms on 8th October 1871 “on view of the body of Robert Brook, deceased”. Mary Brook, a widow, told the Inquest “Deceased was my husband. He was 32 years old & a coal miner. On 27th ult., he set off to work as usual. He died on Saturday.” The Inquest was adjourned until 24th October at The Albion Hotel, Thornhill. The re – convened Inquest on 24th October was adjourned until 21st November 1871 when evidence was given and an open verdict unanimously returned by the Jury as to the cause of the explosion. Robert Brook was badly burned and may have returned home after the incident on the 27th September. He actually died on Saturday 30th September 1871 and was buried at Thornhill Parish Church on 10th October 1871.

Smithy Brook, Edge End, Thornhill well known to Charlotte Schofield. Courtesy Dewsbury Reporter

Mary Brook (nee Schofield) was left a widow with four children under the age of 10 years. She had no option but to re-marry or call upon the Poor House with her children, including Charlotte, aged 10.

On 5th October 1872 Mary Brook (nee Schofield) aged 31, a widow of Thornhill, married 31 year old bachelor Ezra Shires a miner of Middlestown. The couple made their mark on the marriage registration and by 1881 they were living on Foxes Row Netherton with the couple’s three children, Mary’s four children by Robert Brook and Charlotte Schofield who was named as Shires on the census.

Later that year at Christmas 1881 Charlotte Schofield, aged 20, reverted to her birth name and put aside the names Brook and Shires, as she married Richard Kitchen and became Charlotte Kitchen for the rest of her life.

Mary Shires (formerly Brook nee Schofield) of Horbury died in March 1889, aged 46 years, and was buried at Horbury Cemetery on 28th March 1889.

Back to normality. Charlotte and Richard Kitchen had been married for ten years by 1891 and the couple were living on Cluntergate Horbury with their first four children; all were sons and three were at school. Their father, Richard, was a coal miner. By 1901 nine children, including seven sons, had been born to the couple and the family were living on Bulling Back Lane, Horbury.

The three eldest sons were working; one being a miner like his father and two working at Charles Roberts’ Horbury Junction Railway Waggon Works which during WWI also operated in part as a shell and shrapnel plant designed by Roberts.

The couple’s eldest son John Henry was baptised at St. Andrew’s Mission Church, Netherton in the Parish of St. Luke’s Middlestown on 25th June 1882.Twenty years and twelve births later, their youngest son, Harry, was baptised at St. Mary’s Church Horbury Junction on 17th October 1902. Sadly the couple’s eldest son, John Henry, died aged 24, in late 1906 and their elder daughter, Edith, died in early 1908 aged 16.

In March 1911 Richard’s wife Charlotte Kitchen (nee Scofield), aged 50 years, of Spring End, Horbury, passed away and was buried at Horbury St. Peter and St. Leonard’s Church Yard on 14th March 1911.Perhaps, in a way, it may have been a blessing. The Census, dated 2nd April 1911 thus recorded Richard Kitchen as a widower aged 53 years living at Spring End Horbury with six of his surviving sons, four of whom were miners, and his only surviving daughter, Mary Elizabeth. His son, Tom, aged 25 years was living in the eleven – room farmhouse with his childless aunt and uncle, also Thomas, a 62 years old farmer in Sudbrook, Lincolnshire. Tom was working on the farm but perhaps he was also taking the sad news of his mother’s death three weeks earlier, to his aunt and uncle.

On 30th May 1911 George Kitchen, a miner of Horbury aged 22 years married 19 years old Hannah Elizabeth Newton of Middlestown at Thornhill Parish Church. After the end of the war, if not before, Hannah lived at 20, New Scarbro, Netherton. Widow Hannah married George Ridsdale in early 1920.

In late 1915 Richard Kitchen remarried and was joined with Lincolnshire widower Elizabeth Burley. Richard and Elizabeth (with two children, including a daughter called Edith, born 1891), were both widowed in 1911 and may have known each other before Richard came north from Lincolnshire.

On 20th December 1919 Mary Elizabeth Kitchen, aged 29, a rag sorter married William Scott, a miner aged 25 at St.Peter’s Church Horbury. Both gave their address as 2 Sunderland Yard Spring End Road.

On 24th December 1921 Willie Kitchen aged 27, a miner of 46 Spring End Horbury married 23 year old Mary Ann Hammond of 10 Spa Lane at South Ossett Christ Church.

On 21st February 1925 at St. Mary’s Church, Gawthorpe & Chickenley Heath, Harry Kitchen, a miner aged 22, of 44 Spa Street South Ossett married Hilda Simpson aged twenty of 19 Naylor Street Ossett.

In 1921 Richard and his second wife Elizabeth Burley were living in Horbury with their family. In 1939, retired miner, Richard (born 18 March 1858) and Elizabeth (born 18th August 1867) were living together at 26, Sunroyd Hill, Horbury.

Life in war time 1914-1919

On 4th August 1914 Great Britain declared war on the German Empire and the country called on its youth to stand up for freedom. The Kitchen family were to discover that meant that five of their surviving seven sons were of an age when they might be called upon.

THOMAS (TOM) KITCHEN (1884-1916)

THOMAS (TOM) KITCHEN (1884-1916)

Lance Corporal 10455, 7th (Service) Battalion Lincolnshire Regiment

Tom’s army service record has not survived which makes it more difficult to determine his whereabouts in WWI. However it is known that he enlisted at Sleaford in Lincolnshire and joined the 7th (Service) Battalion Lincolnshire Regiment becoming Private 10455, Tom Kitchen. He was subsequently promoted to Lance Corporal.

The 7th (Service) Battalion Lincolnshire Regiment was raised at Lincoln in September 1914 and joined the 51st Brigade in the 17th(Northern) Division.

Photograph courtesy of Pheonix Rotary Horbury.

After initial training close to home, the Division moved to Dorset to continue training and then on 27th May 1915 they moved to camp near Winchester. On 5th July 1915 the Division was informed that it would be retained for Home Defence duties. At midnight this was reversed and instead

Private Tom Kitchen and his battalion proceeded by route march and entrained to Folkestone for embarkation to France on 14th July 1915. They landed at Boulogne at midnight and the 7th Battalion, comprising 29 Officers and 932 other men (Other Ranks), concentrated near St. Omer where they billeted for two days before marching and entraining for Ypres, Belgium.

They moved into the Southern Ypres salient on 21st July for trench familiarisation and then took over the front lines in that area. On 30th July at Hooge a German attack used flame-throwers for the first time and captured strong points but this was reversed by British bombardments in August 1915. In spring 1916 they were in action at the Bluff, south east of Ypres. The Bluff was created from a spoil heap left by the digging of the Ypres-Comines Canal prior to World War I. Today it is a mound of grass-covered terrain that is a provincial park and picnic area.

The Bluff was 30 feet high on the western side with a gentle slope to the east, making it one of the best vantage points in the Ypres Salient. As such, The Bluff was the site of several Battles of Ypres that took place between the Germans and Allied Forces in 1915-1917. In spring 1915, there was constant underground fighting in the Ypres Salient at various sites including The Bluff. Much of the combat required the deployment of new drafts of tunnellers for several months following the formation of the first eight tunnelling companies of the Royal Engineers. The Bluff conflict, as did much of Ypres, amounted to a massive tug-o-war where each side would gain control for a while before yielding it back later on. In the process, there were mammoth casualties on both sides with little or nothing being accomplished in between.

In mid March 1916 the Division left Ypres and moved south to The Somme in readiness for the major allied forces offensive. On 29th March 1916 Private Tom Kitchen was listed as wounded on the Casualty List issued by the War Office; no date of the occurrence was given. Between April and June 1916 Tom was made Lance Corporal. 1st July 1916 the first day of the Battle of the Somme when 19,240 British soldiers lost their lives saw the 7th Battalion Lincolnshire Regiment in reserve for an attack on the village of Fricourt where the enemy held a well defended front. One of the Divisions which led the attack was cut off and annihilated and the Germans turned their machine guns onto waves of British soldiers as they came through no-man’s land, causing more heavy casualties. A second attempt failed miserably and at great cost of manpower.

During the night the Division came out of reserve and on 2nd July 1916 it captured and secured Fricourt but there remained a stiff fight to clear Fricourt Wood where opposition was still strong. The 7th Lincolnshire Regiment was one of four battalions charged with clearing the enemy from the Wood on the morning of the 3rd July 1916.

It was here, near Fricourt, on 3rd July 1916 that Lance Corporal Tom Kitchen suffered a “penetrating wound” which meant a gunshot wound with direct penetration or perforation of the larger joints with or without fracture. Tom was transferred to sick convoy and he was evacuated to one of the Etaples Base Hospital by ambulance train.

Sadly, it was to no avail and Tom died of his wounds on 5th July 1916. He is Remembered with Honour by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) at Etaples Military Cemetery where he is buried. He was 22 years of age. He was posthumously awarded the British and Victory Medals for service overseas in a theatre of war and the 1914-15 Star for his service overseas on or before 31st December 1915. Commonwealth War Graves Commission

Lance Corporal 235140, 6th Battalion King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry. Formerly with 1/4th KOYLI

Lance Corporal 235140, 6th Battalion King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry. Formerly with 1/4th KOYLI

George Kitchen had served with the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry (KOYLI) for nine years before he was killed in action on 16th December 1917. In the absence of his army service records, lost in 1941 in a Luftwaffe raid on central London, other records have been investigated in an attempt to re-create his army service between 1908 and 1917.

It is likely that George signed on with KOYLI on the creation of the Territorial Force in 1908. The former Volunteer Battalion was reorganised as the 4th and 5th Battalions.

The “UK, Soldiers Died in the Great War” records him as enlisting at Ossett; probably at the 4th Battalion KOYLI Drill Hall on Station Road.

Photograph courtesy of Pheonix Rotary Horbury

George would be 18 /19 years old when he signed on in 1908 with the Territorial 1/4th KOYLI for five years with the colours and seven years in reserve. In the absence of war the Territorials purpose was to form a home based presence and they had the option, should war be declared, not to serve overseas.

By August 1914 George would have served at least the five years for which he had signed up.

George forwent his right to remain “at home” and instead took the option to serve overseas. As it was on Saturday, 2nd August 1914 he was most probably with the 4th battalion in camp at Whitby. On Sunday 3rd August it was evident that war was imminent and on 4th August orders were received to return to Wakefield for mobilisation. Due to improvised arrangements for moving the troops the return was delayed. The 1st West Riding Brigade of which 4th KOYLI was a part assembled at Doncaster where it was encamped on the racecourse. Thence it removed to Sandbeck Park because the racecourse was required for the usual race meeting. It removed to Gainsborough on 18th November remaining in billets. There was an unfortunate accident in practising with rafts when three men were drowned. On 26th February the unit moved to York and stayed in billets at the Cocoa Works until it moved overseas via Southampton and Folkestone to join the Expeditionary Force in France on 12th April 1915.

The infantry also crossed from Folkestone to Boulogne, but the mounted troops, artillery, engineers, field ambulances and other divisional troops all went from Southampton to Le Harve.

Progressive instruction in trench warfare commenced on 14th April and later each battalion sent a contingent on a tour of duty lasting twenty four hours into the frontline trenches. On 12th May 1915 the 1/4th Battalion KOYLI came under the command of the 148th (West Riding) Brigade of the 49th(West Riding) Division which comprised several battalions from the Duke of Wellingtons, West Yorkshire and KOYLI Regiments. By 19th April, the Division had completed its concentration north of the River Lys, in the vicinity of Estaires, Merville and Neuf-Berquin.

Private George Kitchen 235140 Medal Index Card recording his embarkation date & his service medal awards (British, Victory & 1914-15 Star).

Before moving on there’s a bit of housekeeping to mention. It is known that George Kitchen served first with the Territorial Force (TF) 1/4th Battalion KOYLI and latterly with the 6th Battalion KOYLI with whom he was serving at the time of his death in December 1917. Because his service record was destroyed it is not possible to identify the date or the reason why he was moved from the 1/4th to the 6th Battalion. It is important to know that date because the 1/4th and 6th Battalions KOYLI took part in different conflicts.

We cannot be certain of the date George moved to the 6th Battalion but when he died he had a six digit service number 235140. These six digit service numbers were only allocated to men serving in the Territorial battalions (like George) and they were first introduced in early 1917. This tells us that George was still in the Territorial 1/4th Battalion in early 1917 (January – March) and so it’s unlikely that he was moved to 6th Battalion until then. With that in mind it is reasonable to assume he was moved from the 1/4th to 6th Battalions on 1st January 1917.We subsequently discovered a press cutting (below) which confirmed our analysis.

NETHERTON SOLDIER KILLED

A COURAGEOUS SOLDIER WHO SET A FINE EXAMPLE

“The people of Netherton have heard with regret of the death in action of Lance-Corpl., George Kitchen, New Scarboro’ Netherton, whose widow received the sad intimation last week that he was killed on December 15th. Mrs. Kitchen has received a sympathetic letter from Corporal Burnham, who stated that her husband was buried by a shell. He was with six others in a shelter, when the enemy began shelling them. They continued for an hour, and every shell went over the shelter, until the range was altered, but finally a shell struck the shelter and buried them all, four of them, including Kitchen, being instantly killed. Captain Skelton has also sent a letter, in which he says that Kitchen was a very good soldier, and one who would be much missed. He was a very courageous soldier, and showed a fine example to his comrades. Lance-Corporal Kitchen was a Territorial and therefore joined up at the outbreak of the war. He was badly gassed on December 19th 1915**, and returned to the fighting line in January 1917. Prior to the war he was employed at Hartley Bank Colliery, and was very much respected by all who knew him”. Wakefield Express 12th January 1917. Courtesy Pheonix Rotary Horbury

Let the Battles commence. By way of reminder the 1/4th KOYLI Regiment took commands from the 148th (West Riding) Brigade and, above that, from the 49th (West Riding) Division. In each of the “Battles” which follow there are occasions where the Division was involved but this does not mean that the 148th Brigade or the 1/4th Battalion took an active part in each of the Battles because there were more Brigades and more Battalions. It does however mean that the Battalion and George Kitchen were there (unless he was injured/ hospitalised) and playing a role on that occasion. When you read the word “Battle” neither should the reader think that there aren’t dangers and life threating enemy activity in between those so-called Battles.

Battle Of Aubers Ridge – 9th May 1915

This was the occasion of the first heavy action for George Kitchen and the Division. It resulted in a German victory and a British disaster. Part of a large Franco-British offensive intended to capitalise on (perceived) reductions in German troop strength due to transfers to the Eastern Front. Planned as a pincer movement the British attackers were to move out after two huge mines had been detonated beneath the enemy’s front line and a short, intensive barrage had softened up the German trenches and cut the barbed wire.

It turned out to be a complete disaster. Our artillery barrage was not of sufficient weight or intensity to break the barbed wire or front trench lines, neutralise the machine-gun posts or artillery lines and didn’t even reach the support trenches. The undisturbed German machine-gun teams were able to bring down heavy fire across the British lines and many of the assault troops were killed while still on their scaling ladders; the front line trenches were soon filled with hundreds of dead and wounded. Those who did get into no man’s land either perished there or on the barbed wire in front of the German lines. Haig ordered that an evening attack with fixed bayonets would be made but the congestion and confusion behind the lines was too chaotic and the second attack was postponed.

It was to be a baptism of fire and a sign of things to come for Private George Kitchen, 1/4th Battalion KOYLI

First Phosgene Gas Attack – Ypres 19th December 1915

This came at Wieltje near Ypres. The result was inconclusive. Gas had been a feature of the war, used by the German army since January 1915 and the British Army eight months later. However on this occasion this was chlorine gas, released from cylinders and left to blow over the trenches in a cloud. It therefore came as no surprise to the British units holding the sector of the Ypres Salient between Frezenburg and Boesinghe when a gas attack was launched on them at 05.00 hours on 19th December 1915.

When the cloud of gas was detected, the alarms were sounded and the troops donned their gas masks and prepared for the follow-up infantry attack. What they did not expect was that the cloud would also carry phosgene, a gas not previously experienced and one their respirators were not designed to cope with. It was fortunate that a strong wind quickly dispersed the gas cloud or casualties would have been even more serious. As it was over 1000 men were incapacitated by the gas and many more by the artillery bombardment, including lacrymatory gas shells which followed.

In the Division’s sector the majority of the casualties were those men who were asleep in the reserve lines and had not put their helmets on in time. There was no large scale German infantry attack to follow. Due to the brisk wind dispersing the gas cloud less than an hour after its launch, British troops were able to mount a good defence, with very few of the raiding parties reaching British lines.

Those that did were repulsed with heavy casualties. A new modified PH Gas Helmet to improve protection against a phosgene attack was issued to the troops in January 1916.

We now know that George Kitchen was gassed on this day and returned to Blighty for rest and recuperations. He returned to the Front Line a year later in January 1917 when he probably joined 6th Battalion.

Battles Of The Somme Battle Of Albert – 1st July 1916

The 49th (West Riding) Division was in reserve on 1st July and assembled in Aveluy Wood. but only the 146th Brigade was called into action. Crossing the River Ancre over Hamel Bridge they moved up to Thiepval Wood from where they were tasked to support the attack on Thiepval village.

Due to congestion with the numbers of wounded in the trenches, only one battalion and one company of were in a position to advance when the attack came at 16.00pm, making little headways against machine-gun posts in Thiepval Fort. The attack being cancelled the rest of the 146th Brigade were diverted to assist in holding their capture of the Schwaben Redoubt, but again the reinforcements were too few and too late and the position was abandoned at 22.30pm.

On 3rd July, 5th York and Lancaster Regiment attacked the village of St- Pierre-Divion, losing 350 casualties in the process.

Battles Of The Somme – Battle Of Bazentin Ridge – 14th July 1916

The battle marked the beginning of the second phase of the Battle of the Somme.

Dismissed by a French commander as ‘an attack organised for amateurs by amateurs’, in contrast to the disaster of the first day of the Somme it turned out to be hugely successful for the British against the German second line defences.

During the battle 49th (West Riding) Division held the trenches of the Leipzig Sector around Thiepval, where they fought off several attacks, including one on trenches held in the early morning of 15th July by troops armed with ‘Flammenwerfer’ or flame throwers.

Battles Of The Somme – Battle Of Pozieres Ridge – 23rd July 1916

Location: Thiepval. An important German defensive position itself, the heavily fortified village of Pozieres was also part of the second-line German trench system on the Somme.

On 22nd July Fourth Army staged a major attack on Pozieres and the O.G. Lines. Although the 1st Australian Division captured and then held Pozieres under heavy retaliatory artillery bombardment and counter-attack, the main attack by the Fourth Army between Pozieres and Guillemont was a costly failure. Fighting in the area continued through into August, 49th (West Riding) Division were out of the front line from 18th July, moving back on 26th July to trenches north of Thiepval in an area held by II Corps, Reserve Army.

Battles Of The Somme – Battle Of Pozieres Ridge – 27th August 1916

In late August 1916 the 49th (West Riding) Division were instructed to prepare, together with 39th

Division, for a joint attack on the ruins of Thiepval village.

Attacking from the north, 146th Brigade were on the left, with two West Yorkshire Regiments the attacking battalions, with their objectives to capture the German lines. Support for the leading battalions would be provided by a third West Yorkshire Regiment.

The 147th Brigade on the right had 4th Duke of Wellington’s Regiment and 5th Duke of Wellington’s Regiment as their attacking battalions. Originally timetabled for 30th August, the attack finally took place on 3rd September.

Both arms of the attack did initially gain some foothold in the trenches, but the failure of 4th Duke of Wellington’s Regiment to capture the machine-gun position left both sides open to enfilade machine-gun fire and they were eventually pushed back by German counter-attacks. Although 49th Division were unable to remain in possession of the German trenches, they held them for as long as they were able, in some instances to the last round of ammunition and last Mills bomb.

Divisional Head Quarters were unable to keep in contact with the attacking battalions because the signallers were all killed or wounded, a number of runners were sent back but failed to gain the British lines. As the numbers of British soldiers still fighting fell, an officer from another unit (who had become mixed up with the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment) gave the order to withdraw.

Battles Of The Somme – Battle Of Flers-Courcelette – 15th September 1916

This battle saw the first use of massed tanks as an offensive weapon.

After the failure of the major Somme Offensive or ‘Big Push’ on 1st July, Haig wanted a breakthrough by mid-September and before the onset of winter. On 15th September an attack was planned to involve 11 Divisions of infantry and mounted cavalry, supported by tanks and artillery across a 12,000 yard front.

49th (West Riding) Division in positions east of Thiepval, during the evening of 17th September, 7th Duke of Wellington’s Regiment, supported by 4th Duke of Wellington’s Regiment, staged a successful attack on trenches leading to a strong point south-east of Thiepval, receiving 220 casualties. On 19th September, 5th Duke of Wellington’s Regiment took over the captured trenches, with 4th Duke of Wellington’s Regiment relieving them on 21st September.

The British soldiers were able to make use of the deep German dug outs to shelter from the enemy bombardments while consolidating their positions, burying the dead both British and German from previous actions and digging assembly trenches for the 18th Division who would soon be making an assault against the ruins of Thiepval village. Relieved on 24th September, 49th Division retired to Lealvillers and Halloy.

1917

From this point, 1st January 1917, until George Kitchen’s death on 17th December 1917, it is assumed thatGeorgehadleftthe1/4thBattalionKOYLIandjoinedthe6thBattalionKOYLI. Thechangeof Battalion also means a change of Brigade and Division. The Brigade is now the 43rd Brigade and the Division is the 14th (Light) Division.

The change does mean that George had a harder time than that which we would have had with the 1/4th Battalion.

The German retreat to the Hindenburg Line 9th February 1917 – 5th April 1917. The First Battle of the Scarpe** 9th April -14th April

The Third Battle of the Scarpe**3rd May -4th May

The battles marked ** are phases of the Arras Offensive

The Battle of Langemark*** 16th August – 18th August

The First Battle of Passchendaele*** 12th October – 20th October

The Second Battle of Passchendaele*** 26th October – 10th November The battles marked *** are phases of the Third Battles of Ypres

By September 1917, maybe a lot earlier, George Kitchen had been promoted to Lance Corporal. He was also having health problems. On 9th September 1917 he was in the No. 2 Canadian Casualty Clearance Station at Remy Siding just south west of Poperinghe (a town due west of Ypres).

In the 1917 campaign alone, 30,000 casualties were brought from the nearby front lines to be treated at the Clearing Station. Casualty Clearing Stations were the closest facilities to the front lines that could provide surgical treatment. They cared for patients until they could be further evacuated to a General Hospital by Ambulance Train.

George Kitchen had contracted Pyrexia also known as Trench Fever. It is estimated to have affected 380,000 to 520,000 members of the British army and had a debilitating effect, leaving a large number of men incapacitated from the moderately serious disease transmitted by body lice. With proper treatment he could expect to be clear in eight days.

On 16th September 1917 George was referred to the 18th General Hospital at Comiers, a village seven km north of Etaples on the French Coast. The Base Hospital was part of the casualty evacuation chain, further back from the front line than the Casualty Clearing Stations. They were manned by troops of the Royal Army Medical Corps, with attached Royal Engineers and men of the Army Service Corps. In the theatre of war in France and Flanders, the British hospitals were generally located near the coast. They needed to be close to a railway line, in order for casualties to arrive (although some also came by canal barge); they also needed to be near a port where men could be evacuated for longer-term treatment in Britain.

On 23rd September 1917 he was moved to No. 6 Convalescent Depot with facilities for 1500 patients at nearby Etaples. Casualties would generally be moved to one of these Convalescent Depots after being discharged from a nearby General or Stationary Hospital, before they were then moved to a Base Depot ready for redeployment. It is not known how long he remained there.

Meanwhile had he been at his station near Ypres on that day he would have been on the Front line encountering the usual hostile artillery and active aircraft. His 6th Battalion were at Warneton, a village to the south of Ypres and east of Messines, which was the focus for operations of the 3rd Australian Division in mid-1917. The village gave its name to strong German defensive line consisting, like most German defensive positions around the Ypres Salient, of mutually-supporting concrete pillboxes and thick belts of barbed wire.

The Battalion was in reserve for the first week in October but by the middle of October they ad moved to Front Line positions albeit with difficulty due the appalling condition of trenches, impassable shell craters and an enemy heavy shelling most of every night and a good deal of the day. October ended with the battalion at Bedford House which wasn’t quite what it promised.

October turned to November and the Battalion were stationed near Ypres. In the wake of 2nd Passchendaele the first ten days found the company were comfortably billeted in tents and the men were cleaning clothes and equipment; making up the roads, trench tramways and numerous working parties.

In mid October the Battalion headed for France to an area 40km east of Boulogne where they billeted, bathed, had concerts, a church parade and a football match. During November the “only” casualties were two other ranks wounded.

There was more of the same at the beginning of December 1917. The battalion held the front line between 9th -12th December in circumstances where the trenches and shell craters were full of putrid water propped and the enemy held the upper hand such that it was safe only for the battalion to move during the hours of darkness. The battalion also suffered a heavy endemic of trench foot and although they were in the support line on 16th & 17th December they were instructed to take over the front line on the 17th December 1917.

This was the day that George Kitchen was killed in action. His body was never found which suggests enemy shelling or a collapse of the propping. He is remembered on the Tyne Cot Memorial Panel 108-111. I can think of no better place for George Kitchen to be remembered and honoured.

https://www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/835047/george-kitchen/

The Tyne Cot Memorial is one of four memorials to the missing in Belgian Flanders which cover the area known as the Ypres Salient which was formed during the First Battle of Ypres in October and November 1914, when a small British Expeditionary Force succeeded in securing the town before the onset of winter, pushing the German forces back to the Passchendaele Ridge. The Second Battle of Ypres began in April 1915 when the Germans released poison gas into the Allied lines north of Ypres. This was the first time gas had been used by either side and the violence of the attack forced an Allied withdrawal and a shortening of the line of defence.

There was little more significant activity on this front until 1917, when in the Third Battle of Ypres an offensive was mounted by Commonwealth forces to divert German attention from a weakened French front further south. The initial attempt in June to dislodge the Germans from the Messines Ridge was a complete success, but the main assault north-eastward, which began at the end of July, quickly became a dogged struggle against determined opposition and the rapidly deteriorating weather. The campaign finally came to a close in November with the capture of Passchendaele.

The Tyne Cot Memorial – George Kitchen 1914/15 Star, British & Victory Medals

George was posthumously awarded the British and Victory medals for service in a theatre of war and the 1914-15 Star for serving overseas in a theatre of war

WILLIE KITCHEN (1893 – 1964) Private 17332, 9th Battalion King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry Private 36995 6th South Lancashire (Prince of Wales) Regiment

Willie Kitchen’s Medal Index Card. He embarked as KOYLI & was demobilised as South Lancs

Willie Kitchen embarked for France on 11th September 1915 and was subsequently awarded the British, Victory and 1914-15 Star for his services overseas in a theatre of war. His Army Service record has not survived but it appears that he was demobilised at the end of his service on 9th April 1919 when he was posted to Class Z Reserve. Soldiers discharged to Z Reserve could be recalled in the event that Germany did not honour the Armistice. Z Reserve was abolished on 31st March 1920. Willie probably enlisted in 1914, perhaps at the same time as his two brothers, Thomas and George who sadly lost their lives in service. Willie served his four years in the army with two Regiments;

9th (Service) Battalion KOYLI was formed at Pontefract in September 1914 as part of K3 and came under command of 64th Brigade in 21st Division. Moved to Berkhamsted and then to Halton Park (Tring) in October 1914, going on to billets in Maidenhead in November. returned to Halton Park in

April 1915 and went on to Witley in August. September 1915 : landed in France.

6th (Service) Battalion South Lancashire (Prince of Wales Volunteers) Regiment

Formed at Warrington in August 1914 as part of K1 and moved to Tidworth, under command of 38th Brigade in 13th (Western) Division. Moved to billets in Winchester in January 1915 before going next month to Blackdown. Sailed from Avonmouth in June 1915. Landed at Cape Helles (Gallipoli) 7-31 July then moved to Mudros. Landed at Anzac Beach 4 August 1915.

20 December 1915 : evacuated from Gallipoli and went to Egypt via Mudros. February 1916 : moved to Mesopotamia (Iraq)

In the absence of Willie’s Army service record it has not been possible to determine when he moved from KOYLI to South Lancashire Regiment.

In 1939 Willie and Mary Ann (died 1974) were living at 12 Whinfield Terrace, Ossett. They appeared to have several children. Muriel (1922),Sylvia (1925), Ernest (1927), Richard (1934 – 1937).

Whinfield Terrace on left looking towards camera. Dews Terrace on road side

Willie of 12 Whinfield Terrace died at Snapethorpe Hospital on 6th January 1964 when Administration of his estate was granted to his widow Mary Ann. He was buried at Manor Road Burial Ground where his wife and their infant child Richard are also buried. Willie’s brother, Ernest (died 1952 aged 54 years) was buried there in 1952.

Whinfield Terrace on left looking towards camera. Dews Terrace on road side

Willie of 12 Whinfield Terrace died at Snapethorpe Hospital on 6th January 1964 when Administration of his estate was granted to his widow Mary Ann. He was buried at Manor Road Burial Ground where his wife and their infant child Richard are also buried. Willie’s brother, Ernest (died 1952 aged 54 years) was buried there in 1952.

Willie Kitchen was awarded the British and Victory Medals for service overseas in a theatre of war and the 1914-15 Star for service on or before 31st December 1915.

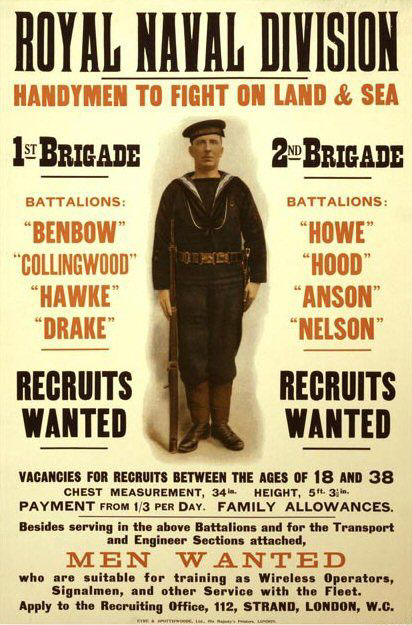

Ordinary Seaman K.W./846, Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve Collingwood Battalion

Fred Kitchen, a collier, aged 28 years, 5’ 3” tall with medium complexion, brown hair and grey eyes left his home and family at Spring End Horbury in August 1914 and enlisted with the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry on 30th August 1914 shortly after Great Britain declared war on the German Empire. On the 8th September 1914 Fred, a non – swimmer, joined the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve also known as the 4th (Collingwood) Battalion. It was named after Vice Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood who served alongside Lord Nelson in the Napoleon Wars. The Battalion took its command from the 1st Brigade in the 63rd (RNVR) Division. The task of the Division was to seize and hold ports to enable the Royal Navy to operate from them.

The Battalion was one of eight formed in 1914 by Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, consisting mainly of naval reservists and recruits not required on board ships. The Division initially formed in tented camps at Walmer (1st Brigade) and Betteshanger (2nd Brigade) near Deal in Kent while awaiting the building of a permanent camp at Blandford.

The Royal Naval Division (RND) were deployed to Antwerp in October 1914 to take over trenches from Belgians surrounding Antwerp. Savaged by German attacks, the Division withdrew but many men were lost or interned (Neutral Netherlands) or seized as POW. The RND were deployed to Antwerp in October 1914 to take over trenches from Belgians surrounding Antwerp. Savaged by German attacks, the Division withdrew but many men were lost or interned (Neutral Netherlands) or seized as POW.

The Royal Naval Division (RND) were deployed to Antwerp in October 1914 to take over trenches from Belgians surrounding Antwerp. Savaged by German attacks, the Division withdrew but many men were lost or interned (Neutral Netherlands) or seized as POW. The RND were deployed to Antwerp in October 1914 to take over trenches from Belgians surrounding Antwerp. Savaged by German attacks, the Division withdrew but many men were lost or interned (Neutral Netherlands) or seized as POW.

The Royal Marine Brigade was formed at once and was moved to Oostende on 27 August 1914, although it returned four days later. On 20 September it arrived at Dunkirk with orders to assist in the defence of Antwerp. The two other Brigades moved to Dunkirk for the same purpose on 5 October 1914. In the haste to organise and move the units to Belgium, 80% went to war without even basic equipment such as packs, mess tins or water bottles.

No khaki uniform was issued. The two Naval Brigades were armed with ancient charger-loading rifles, just three days before embarking. The Division was originally titled the Royal Naval Division, and was formed in England in September 1914. At this stage, it had no artillery, Field Ambulances or other ancillary units.

By late August 1914, the Belgian Army had been cut off from the rest of the Allies by the advance of the German troops and had fallen back to the fortified city of Antwerp. The city came under siege.

After pleas of help from the Belgians (and because of the fear of the security of the channel ports) the Royal Naval Division were sent to help lift the siege. They arrived in Dunkirk on 3rd October 1914, just as the Germans were breaking through the outer ring of Antwerp’s fortifications. By the 6th /7th October the RND arrived in the vicinity of Antwerp (some accounts say they travelled by recommissioned London buses).

Fighting was fierce and Belgian forces were soon overwhelmed. Things did not go well and having to retreat as the 150,000 or so Germans advanced, elements of the 12,000-strong Royal Naval Division suffering heavy casualties from German artillery, whilst they themselves had none with which to reply or hold off their advance.

Continual bombardment and the advancement of the German troops through the city’s inner defences forced the Belgians to cede the city. The RND, still a new force with limited equipment or training, were forced into a chaotic retreat. Around 1,500 from the 1st Royal Naval Brigade made it to the Dutch border to avoid capture “as there would be no mercy from the Germans“. Those that made it were disarmed and interned under the Hague Convention (1907) that obliged the then neutral Netherlands to disarm and intern any military personnel crossing into its territory. RND units that managed to successfully withdraw from Antwerp returned to England, arriving on 11th October 1914.

Ordinary Seaman Fred Kitchen was one of those men to be interred. So, having been at the front for barely a week, the war was effectively over for those now in the Netherlands, who were quickly sent on a 14-hour train journey to barracks in Groningen. The Royal Naval Division record cards shows that, in spite of being a prisoner, the men were allowed home leave, sometimes for prolonged periods of time. The internment camp became known to the locals as the ‘English Camp’, but to those interned as ‘HMS Timbertown’, which gives you some idea of how it was built. Many officers were housed at hotels in Groningen.

On 11 November 1918 the Armistice was signed and as soon as 15 November 900 British left for England via Rotterdam. There were already 300 men on leave in England and the British working outside of the camp were to leave later. Commodore Henderson and 50 of his men remained to settle camp business. The English Camp was officially terminated per 1 January 1919.

1st Brigade Royal Naval Division 1914 -1918 Groningen; English Camp or HMS Timbertown

It wouldn’t be right to leave the reader with the impression that this was all the Royal Naval Division did in WWI. Far from it.

After a lengthy period of refit and training (scattered in various locations, and still short of many of the units that ordinarily made up the establishment of a Division), the Division moved to Egypt preparatory to the Gallipoli campaign.

By the end of the Division’s part in the Gallipoli campaign, very few men with sea service remained. The Division transferred from the authority of the Admiralty to the War Office on 29 April 1916 and was redesignated as the 63rd (Royal Naval) Division on 19 July 1916. The Division moved to France, arriving Marseilles 12-23 May 1916, after which it remained on the Western Front for the rest of the war.

On various occasions it fought at Gallipoli, The Somme, Arras and Ypres. This unique Division was demobilised in France by April 1919. It had suffered over 47,900 casualties.