Young men and women in 1914, like their parents, expected the war to be short. Music hall songs were patriotic and optimistic. Women were expected to wait at home patiently or, if they were from working-class homes, to join munitions factories. “Keep the home fires burning,” they were abjured. “Though your boys are far away, they will soon come home.” Had they been injured, however, there would have been very few nurses to look after them.

Florence Nightingale formed the first nucleus of a recognised Nursing Service for the Army in the Crimean War, 1854. Following the war she fought to institute the employment of women nurses in military hospitals and by 1860 she had succeeded in establishing an Army Training School for military nurses at the Royal Victoria Hospital, Netley.

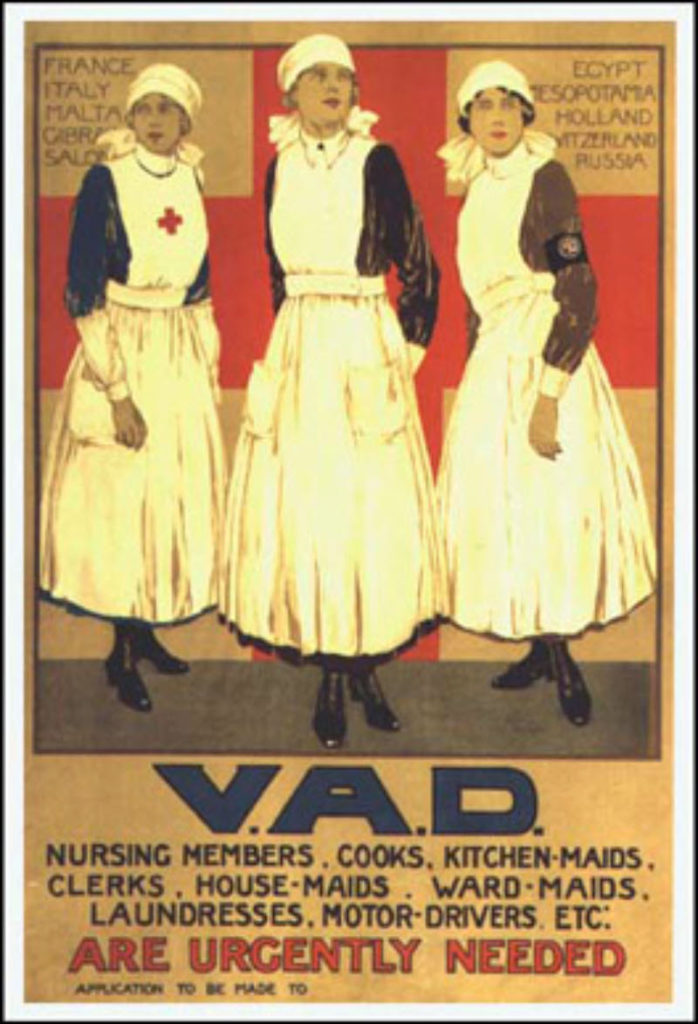

Nursing played a crucial role during the First World War. Emergency medical practices evolved enormously during the war years (1914–1918) and thousands more medical workers were involved than in previous wars. New and innovative practices included blood transfusions, the use of antiseptics, local anesthetics, and painkillers. During the course of the War in the United Kingdom, 38,000 members of the Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) served in hospitals or worked as ambulance drivers and cooks.

Because the British Army was so resolutely opposed to all female military nurses except the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service (QAIMNS), early volunteers from Britain were obliged to serve instead with the French and Belgian forces. Many of these early volunteers were from aristocratic families and their servants. Powerful women who ran large families and large estates were well versed in management and saw no great problems in managing a military hospital instead. Their confidence in their own abilities was impressive.

Whatever bureaucratic obstacles were put in their way, the huge and bloody tide of casualties by the spring of 1915 simply swept them away. Even the British Army’s top brass yielded to the combined pressures of need and confident commitment. You can read here more of the nursing organisations which flowered and grew in WWI in spite of the early opposition.

These then are the stories of some Ossett women who volunteered to serve their Country and to administer their skills and compassion to servicemen in times of their greatest need.

Above: This WW1 photograph depicts members of the Army Nursing Corps including a sister and five staff nurses. Also in the group are Red Cross and St. John V.A.D. helpers and convalescent soldiers in their blue hospital uniforms – although one man appears to be wearing a suit of lighter colour. The soldiers in khaki are probably orderlies. In the background more convalescents look on.

The main trained corps of military nurses was the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service (QAIMNS). It was founded in 1902 at the time of the Boer war and in 1914 was less than 300 strong. At the end of the war four years later it numbered over 10,000 nurses. In addition several other organisations formed earlier in the century had the nursing of members of the armed services as their main purpose; for instance, the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry launched in 1907.

Apart from them there were thousands of untrained women working as midwives or nurses in civilian life, but they had little or no experience of working with soldier patients and their status in society was little better than that of domestic servants.

Because the British Army was so resolutely opposed to all female military nurses except the QAIMNS, early volunteers from Britain were obliged to serve instead with the French and Belgian forces. Many of these early volunteers were from aristocratic families and their servants. Powerful women who ran large families and large estates were well versed in management and saw no great problems in managing a military hospital instead. Their confidence in their own abilities was impressive.

The most famous of these women was the Duchess of Sutherland, nicknamed “Meddlesome Millie.” Soon after war was declared she and other grand ladies like her took doctors and nurses to France and Belgium, organising their own transport and equipment to set up hospitals and casualty clearing stations.

Whatever bureaucratic obstacles were put in their way, the huge and bloody tide of casualties by the spring of 1915 simply swept them away. Even the British Army’s top brass yielded to the combined pressures of need and confident commitment.

At this stage of the war women began to be invited to serve in a range of capacities, of which nursing was one. Thousands of young women from middle-class homes with little experience of domestic work, not much relevant education and total ignorance of male bodies, volunteered and found themselves pitched into military hospitals.

They were not, in most cases, warmly welcomed. Professional nurses, battling for some kind of recognition and for proper training, feared this large invasion of unqualified volunteers would undermine their efforts. Poorly paid Voluntary Aid Detachments (VADs) were used mainly as domestic labour, cleaning floors, changing bed linen, swilling out bedpans, but were rarely allowed until later in the war to change dressings or administer drugs.

The image and the conspicuous Red Cross uniforms were romantic but the work itself exhausting, unending and sometimes disgusting. Relations between professional nurses and the volunteer assistants were constrained by rigid and unbending discipline. Contracts for VADs could be withdrawn even for slight breaches of the rules.

The climate of hospital life was harsh but many VADs also had to cope with strained relations with their parents and other older relatives. The home front in WW1 was very remote from the fronts where the battles were fought.

The war produced medical issues largely unknown in civilian life and not previously experienced by doctors or nurses. Most common were wound infections, contracted when men riddled by machine gun bullets had bits of uniform and the polluted mud of the trenches driven into their abdomens and internal organs. There were no antibiotics, of course, and disinfectants were crude and insufficiently supplied.

In Britain much work was done to deal with infected wounds but thousands died of tetanus or gangrene before any effective antidote was discovered. Towards the end of the war, a few radical solutions emerged. One of these was blood transfusion effected simply by linking up a tube between the patient and the donor, a direct transference.

When the war ended, most VADs left the service though a few of the most adventurous went away to other wars. They went home to a world in which men were scarce. It was as much the huge loss of hundreds of thousands of young men in France, Belgium and Great Britain, not to speak of Russia and of course Germany, that advanced the cause of equality and the extension of the suffrage to women.

Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service

QAIMNS was part of the army before the war, adopting its name in 1902 from the predecessor Army Nursing Service of 1881. Formation of a QAIMNS Reserve and the Territorial Force Nursing Service followed. In the first weeks of the war these services mobilised for duty. Greatly expanded (from 3,000 staff in 1914 to 23,000 in 1918 including TFNS), they served throughout the war and were present in all theatres.

The Voluntary Aid Detachments

In 1904 a Government report was submitted on the Japanese voluntary aid system, which was to prove influential. In 1905 the British Red Cross was reorganised and links established with the War Office and later with the Territorial Forces Associations. In August 1909 the War Office started its scheme of voluntary aid organisation based on male and female Voluntary Aid Detachments to the Sick and Wounded (VADs) to be organised for their local Territorial Forces Associations by the Red Cross. Basic first aid and nursing training was to be given by the St John Ambulance Brigade. Over 47,000 VADs were employed on various tasks, only the best known being nursing, in August 1914. By 1920 there were more than 82,000. Both men and women could join the VADs.

Most of the Ossett women featured in the accompanying biographies were VADs.

First Aid Nursing Yeomanry

A rather select higher-class organisation that had existed since formation in 1907, the FANY worked with the Red Cross organisations, principally as ambulance drivers. There were just fewer than 120 members of the group in France in August 1918. FANY went on to survive another war and indeed still operates today, although the nature of its work and the make-up of its staff has changed somewhat since 1918.

Territorial Force Nursing Service

Established as part of the new Territorial Force in the army reforms of 1908, the TFNS was the equivalent to the regular army’s QAIMNS.

Women’s Hospital Corps

A very early war time voluntary group formed in September 1914. Dr’s Flora Murray and Louisa Garrett Anderson established military hospitals for the French Army in Paris and Wimereux, their proposals having been at first rejected by the British authorities. The latter eventually saw sense and the WHC established a military hospital in Endell Street, London staffed entirely by women, from chief surgeon to orderlies.

Above: A procession of women, led by a band, demanding the right to enter the war services in 1915. The banner reads: “The situation is serious. Women must help to save it.”

Scottish Women’s Hospitals

Founded by the extraordinary Dr Elsie Maud Inglis, who was not only a suffragette but one of the earliest qualified female medical doctors. Her idea was for the Scottish Suffrage Societies to fund and staff a medical hospital; the military authorities told her to “Go home and sit still.” Not to be held down, Inglis pressed forward. The first unit moved to northern Serbia in January 1915 and by 1918 there were 14 such units, working with each of the Allied armies except the British. Dr Inglis was taken prisoner of war in Serbia in 1915, but was repatriated. She immediately moved with another unit to Russia. Evacuated home after the revolution there, she died in Newcastle the day after her return home in November 1917. One of the Ossett women, Constance Elliot Birks, featured in an accompanying biography, served with the Scottish Women’s Hospitals in Belgium.

Following the outbreak of the First World War on 4 August 1914, the British Red Cross formed the Joint War Committee with the Order of St John. They worked together to pool fundraising activities and resources. The Committee supplied services and machinery in Britain and in the conflict areas abroad. It also organised nursing staff in the UK and abroad to support the naval and military forces.

The nursing of sick and wounded soldiers during the war was carried out by a number of trained and voluntary nursing staff. Trained nurses were licensed professionals who had spent years training in a hospital with a recognised school. In every large hospital there was a matron, sisters, nurses and probationers. Voluntary nurses, better known as Voluntary Aid Detachments (VADs), were people who willingly gave their time to care for wounded patients.

VAD members were not entrusted with trained nurses’ work except in an emergency when there was no other option. At the start of the war, VADs were known to have ‘fluttered the dovecotes of professional nursing’ due to their enthusiastic desire to nurse wounded soldiers. Their initial purpose was to support military and naval medical services during times of war. However, it was soon realised that detachments could play an important role during the First World War in caring for the large number of wounded soldiers.

When the Joint War Committee took control of the VADs and trained nurses, these two departments were placed under the direction of Dame Sarah Swift, who had been matron of St Guy’s Hospital.

From the outset of the war until November 1918, trained nurses were sent abroad at short notice under the banner of the Red Cross. Over 2,000 women offered their services in 1914, many declining a salary, and from this list individuals were despatched to areas of hostility including France, Belgium, Serbia and Gallipoli. From 1915 onwards they were joined by partially trained women from the VADs who were posted to undertake less technical duties.

There are reports of unemployed trained nurses complaining that the wounded abroad were suffering from the lack of professional assistance whilst many women were simply waiting at home, keen to offer their services. Yet the War Office and the Joint Committee considered that with an escalating number of wounded servicemen being sent home, fewer nurses were required abroad. This resulted in an increase in the ranks of paid nurses being employed in hospitals at home.

On the 16th August 1909, a scheme began to organise voluntary aid in England and Wales. The Red Cross’ role was defined as assisting the government in wartime by helping the territorial medical service. A similar scheme for Scotland followed in December 1909.

The Red Cross and The Order of St John of Jerusalem organised voluntary aid detachments (VADs), made up of men and women, in every county to carry out transport duties and staff rest stations and hospitals. By October 1910, 202 detachments had been registered with over 6,000 volunteers. Membership of the detachments grew still further on the outbreak of the First World War when the Joint War Committee was formed.

VADs had to be between 23 and 38 years old. Women under 23 were rarely registered as nurses with the Red Cross, but the rule was not enforced for women over 38 who had no diminished capacity.

From the beginning of the war until the armistice, trained nurses were always available to be sent out by the Red Cross. Partially trained VADs, working under the Joint Committee, carried out duties that were less technical, but no less important, than trained nurses. They organised and managed local auxiliary hospitals throughout Britain, caring for the large number of sick and wounded soldiers arriving from abroad.

Training was at the heart of the VAD. During peacetime, the volunteers had practised their skills by helping in hospitals and dispensaries and running first aid posts at public events. When war broke out they were ready to use these skills. A few VADs had already gained experience of nursing during the Balkan wars. The number of volunteers increased dramatically in the early years of the First World War and by 1918 there were over 90,000 British Red Cross VADs.

Voluntary Aid Detachments were organized in each county and consisted of men and women:

The Men’s Detachment

1 Commandant

1 Medical Officer

1 Quartermaster

1 Pharmacist

4 Section Leaders

48 Men

The Women’s Detachment

1 Commandant (man or woman)

1 Medical Officer (if the commandant is not a doctor)

1 Lady Superintendent (who should be a trained nurse)

1 Quartermaster (man or woman)

1 Pharmacist

20 women, of whom four should be qualified as cooks

Each Red Cross detachment was registered by the Council of the British Red Cross Society, given a number by the War Office, formed part of the Technical Reserve, and was inspected annually by an Inspecting Officer detailed by the General Officers’ Commanding. Those women who joined the VAD were trained in cookery, sanitation, bandaging and dressings, washing of bodies and linens, and proper procedure before, during, and after surgeries. To become a VAD Member, a woman would write to her Country Director for instructions, or to the Secretary of the Joint Women’s VAD Department, which was stationed inside Devonshire House, who would then forward the name of her local County Director.

The nature of the fighting during the Great War led to a huge number of injured soldiers and the existing Military medical facilities in the United Kingdom were soon overwhelmed. A solution had to be found quickly and many civilian hospitals were turned over to military use, a large number of asylums were also converted to military hositals, with the asylum patients being sent home, often to unprepared families.

The nature of the fighting during the Great War led to a huge number of injured soldiers and the existing Military medical facilities in the United Kingdom were soon overwhelmed. A solution had to be found quickly and many civilian hospitals were turned over to military use, a large number of asylums were also converted to military hositals, with the asylum patients being sent home, often to unprepared families.

As demand for beds grew, large buildings such as Universities and hotels were transformed into hospitals and wooden huts sprang up in hospital grounds and at army camps to cope with the huge numbers. Additional nursing staff were needed and this was met by a mixture of qualified nurses and volunteers.

A soldier who was injured in the field would be treated firstly at a Regimental Aid Post in the trenches by the Battalion Medical Officer and his orderlies and stretcher bearers, then moved to an Advance Dressing Station close to the front line manned by members of The Field Ambulance, RAMC.

If further treatment was needed he would be moved to a Casualty Clearing Station, a tented camp behind the lines and then if required moved to one of the base hospitals usually by train, the seriously wounded were taken back to Britain by Hospital Ship and onto the relevant hospital for further treatment. With the wide range of serious injuries being faced, hospitals began to specialise in certain types of injury in order to provide the best treatment, with soldiers being sent by train to the relevant hospital. Many large houses and hotels were used as Convalescent Hospitals.

Those being treated wore a blue uniform with a red tie, known as “Hospital Blues” (left), once a soldier was deemed fit enough to leave convalescence, he would return to one of the Command Depots for the rehabilitative training after which they would be allocated to a battalion, frequently a different battalion or regiment to that in which he had previously served, as his place would have been taken by another man to maintain numbers.

At the outbreak of the First World War, the British Red Cross and the Order of St John of Jerusalem combined to form the Joint War Committee. They pooled their resources under the protection of the red cross emblem. As the Red Cross had secured buildings, equipment and staff, the organisation was able to set up temporary hospitals as soon as wounded men began to arrive from abroad.

The buildings varied widely, ranging from town halls and schools to large and small private houses, both in the country and in cities. The most suitable ones were established as auxiliary hospitals. Auxiliary hospitals were attached to central Military Hospitals, which looked after patients who remained under military control. There were over 3,000 auxiliary hospitals administered by Red Cross county directors.

In many cases, women in the local neighbourhood volunteered on a part-time basis. The hospitals often needed to supplement voluntary work with paid roles, such as cooks. Local medics also volunteered, despite the extra strain that the medical profession was already under at that time. The patients at these hospitals were generally less seriously wounded than at other hospitals and they needed to convalesce. The servicemen preferred the auxiliary hospitals to military hospitals because they were not so strict, they were less crowded and the surroundings were more homely.

When a new auxiliary hospital opened, Red Cross headquarters were usually asked to provide nursing staff. Nursing staff were generally local residents, but some detachments travelled or moved to work in auxiliary hospitals across the UK.

The first matron interviewed commandants who visited headquarters to discuss the supply of nurses for their hospitals and sometimes to report the behaviour of nurses. She also interviewed all nurses who arrived at headquarters from a hospital. In cases where they were sick, nurses were sent to hospital, home to friends or to the Queen Alexandra’s fund for sick nurses, which offered hospitality to nurses in need of rest or a holiday.

By courtesy of the railway companies, nurses going on holiday or sick leave and travelling in uniform were allowed one railway voucher every six months. This entitled them to a return ticket for a single fare.

The first matron kept a record of the nurses sent out, the hospitals to which they were sent and whether the Joint War Committee or the hospital authorities were responsible for their salary. Nurses who were sent back because they had not performed satisfactorily were allowed three trials. If they did not get on at any of the three hospitals to which they were sent, they were either dismissed or advised to resign.

During the war a new system of “Special Service” supplied Red Cross nursing members to Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC). In Military Hospitals, previously staffed exclusively by army nurses and orderlies from the RAMC, the scheme introduced VADs to the military hospitals. The VADs were posted by the Joint Committee of the British Red Cross Society and the Order of St John at Devonshire House. Special Service VADs were also sent to Red Cross hospitals, both in England and abroad.

After the first few months, the general rule was that nurses were only sent abroad after they had served for at least two months under the Joint War Committee in an auxiliary hospital at home and had received a favourable report. The quality of care by the Red Cross meant that every nurse employed to carry out work in a hospital overseas came up to the standard of a sister, staff nurse or even a matron in an average London hospital.

Sources

1. Baroness Williams of Crosby writing for the BBC Magazine

2. The British Red Cross – all you need to know about WW1 Nursing

3. Scarlet Finders – all you need to know about WW1 Nursing