Bennett Brook was born on 29 July 1891 the first child, and only son, of Fredrick and Lilly Brook (nee Hey). Bennett’s siblings were Alice, Ada and Annie. Another sibling, Bertha, was born in 1901, but sadly died, aged 3, in 1904. Bennett’s father, Fredrick, rented and worked Sowood Farm, Ossett from around the time of Bennett’s birth, but the farm had been owned and worked by Bennett’s ancestors since 1676.

Later in his life, Bennett was to purchase Sowood Farm, and it remains to this day in the ownership of the Brook family. It was natural therefore that Bennett grew up helping his father on the farm and learning the business so that he might continue the Brook family tradition. They were rudely interrupted in 1914 by the Germans. Fredrick Brook was too old for service in World War 1 and farmers’ work at home was an important part of the War effort. However, his son Bennett was subject to the provisions of the Military Service Act 1916, which introduced conscription and, to remain in farming, he would have had to claim exemption from service on the grounds of his work at Sowood Farm. A local tribunal would decide if it was expedient for him to be engaged in non-military work.

On the 31st May 1917, Bennett Brook, aged 25, joined the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry (KOYLI). The first posting of 116622 Private B. Brook was to the Ottringham Training Camp, near Hull and on the 20th August 1917 he was transferred to the Machine Gun Corps (MGC) for training at Clipston Camp near Nottingham.

Bennett Brook was a farmer and a strong, well-built lad in his mid 20s. The Army knew he was perfectly built for handling the heavy Vickers machine gun, which weighed over 28 pounds; the tripod 20 pounds and the water to cool the gun, another 10 pounds. Of the 170,000 men and officers serving the Machine Gun Corps in WW1, 69,000 became casualties of whom 12,500 were killed. Not surprisingly, the men of the Machine Gun Corps became known as “The Suicide Squad.”

Bennett’s WW1 service record has not survived, but his personal 1918 War Diary has, and it records his service in France during 1918 with his rise through the ranks to acting Lance Corporal then Corporal, which subsequently put him in charge of a Machine Gun team of four to six men. The Diary, which is reproduced elsewhere, tells of his exploits in France and Flanders between the 1st of January 1918 and the 22nd of October 1918. The 35th Division Machine Gun Company Regimental Diaries1 have also been consulted to reconstruct Bennett’s service.

Following 6 weeks training at Clipston in late August 1917 and the usual 2-7 days Embarkation leave, it is likely that he was serving overseas by October 1917. Bennett Brook was posted to the 35th Division and was to use his training to good effect in the 106th Machine Gun Company: one of four Machine Gun Companies attached to the 35th.

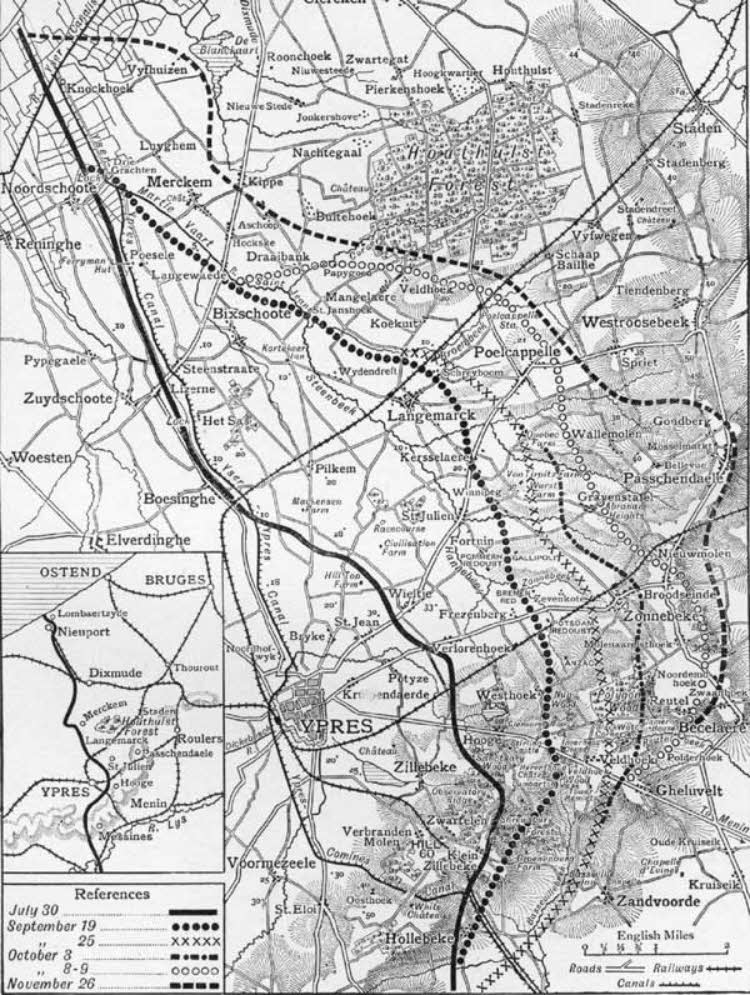

Bennett at 3rd Ypres; the second Battle of Passchendaele October 1917

In October 1917 the Division was heavily involved in fighting at Houthulst Forest and Passchendaele, which were both phases of the 3rd Battles of Ypres. On the 25th October 1917, Bennett posted home a Field Card from France in which he says “Leaving here tonight, going nearer to the lines.” The second Battle of Passchendaele began the day after on the 26th October 1917 and the 106th MGC relieved the 105th MGC whilst the 104th MGC went forward in support of the 241st MGC. The Suicide Squad were set to play a major part in one of the most infamous battles of WW1.

In words taken from the Despatches of Field Marshall Sir Douglas Haig, Commander in Chief of the British Armies in France and Flanders:

“After the middle of October the weather improved, and on the 22nd October two successful operations, in which we captured over 200 prisoners and gained positions of considerable local importance east of Poelcappelle and within the southern edge of Houthulst Forest, were undertaken by us, in the one case by east-county and Northumberland troops (18th and 34th Divisions), and in the other by west-county and Scots battalions (35th Division, Major- General G. Mc. Franks) in co-operation with the French.

The following two days were unsettled, but on the 25th October a strong west wind somewhat dried the surface of the ground. It was therefore decided to proceed with the Allied operations which had been planned for the 26th October.

At an early hour on that morning rain unfortunately began again and fell heavily all day. The assembling of our troops was completed successfully none the less, and at 5.45 a.m. English and Canadian troops attacked on a front extending from the Ypres-Routers Railway to beyond Poelcappelle.” 2

Above: The ruins of Passchendaele village. The church stood on the mound in the background. Photo from the Michelin Guide to Ypres.

This preoccupation with the weather had plagued the Allied forces since the campaign known as the 3rd Battle of Ypres began on the 31st July 1917. The second Battle of Passchendaele on the 26th October 1917 was merely the last phase of this gloomiest drama in British military history. The first phase began on July 31st, and involved a mass attack on carefully chosen targets.

The area in which the Campaign was fought had been reclaimed from marshland over centuries and only a network of dykes enabled it be farmed. By mid October l917 these drainage networks had been destroyed by months of bombardment turning the battlefield into a quagmire.

The July attack started poorly and continued in the same way despite the British Artillery strength. This totalled 3091 guns, of which 999 were heavy – an average of one gun to every six yards. During the bombardment four and a quarter million shells were fired (£22m worth). It meant that four and three quarter tons were thrown for every yard of the front. This was real “mud and bullets.”

The Germans had adopted a strategy better suited to the conditions and, instead of the linear trench systems, they used a system of disconnected strongpoints and concrete pillboxes whereby the ground was held as much as possible by machine guns and as little as possible by men. These techniques, augmented by the German’s use of mustard gas seriously interfered with the British Artillery.

By mid-August 1917 the first day’s objectives still hadn’t been achieved in the wettest summer for years. The second phase involved close artillery support on a narrow front, where troops would reach targets and then wait for the guns to be bought up; it also had dry weather. Three successive attacks struck three offensive victories against the Germans across September.

However Britain was still short of victory despite these successes, and Haig decided to continue the advance as he wanted to capture the high ground, Passchendaele, as a secure winter base. Torrential rain continued throughout September and early October, which made the battlefield a worse morass than ever.

In order to consolidate the captured positions, it was necessary for the British to take the village of Passchendaele, which stands on the high ground dominating the plain of Flanders to the east of Ypres. A fresh offensive was accordingly begun at dawn on the 26th October 1917.

In the French sector, the troops, after wading through the St. Janshoek and the Corverbeek streams with the water up to their shoulders, stormed the village of Draeibank, Papegoed Wood, and many fortified farms.

The next day fresh progress, of more than a mile, was made on both sides of the Ypres-Dixmude Road, along a front of two and a half miles. The villages of Hoekske, Aschhoop, Merckem, and Kippe were captured, and the western edges of Houthulst Forest reached.

Above: The 3rd Battle of Ypres successive stages of Allied advances July 30th-November 26th 1917.

On the 28th October, the advance continued , in co-operation with the Belgians. The French took the village of Luyghem, and the Belgians Vyfhuyzen. The British, on their part, advanced in the direction of Passchendaele, as far as the southern slopes of the village, capturing a whole series of positions east of Poelcappelle.

On 30th October, British and Canadians continued their attacks, and in spite of the enemy’s desperate resistance, reached the first houses of Passchendaele. On the following days they improved their positions. The struggle at this juncture was very bitter, Hindenburg having shortly before issued an order stating: “Passchendaele must be held at all costs, and retaken if lost.”

On the morning of 6th November 1917, the British resumed the offensive. The Canadians, after bloody engagements to the north and north-west of Passchendaele, captured the hamlets of Mosselmarkt and Goudberg, and finally carried Passchendaele. On the evening, Ypres was completely cleared; and from the top of the Passchendaele Hills the valiant British troops could see, stretching away to the horizon, the Plain of Flanders, which had been hidden from the Allies since October, 1914. This combat was most remembered for the hellish swamp of corpses and mud and carnage. This was warfare at its very worst.

Passchendaele was taken on 6th November 1917 but the result was a Ypres Salient even more open to attack from the Germans, no enemy collapse, and a quarter of a million allied casualties, and probably at least as many among the Germans. As with the Somme, Passchendaele has been called a success and a failure. A success because it eroded the German army’s fighting ability, a failure because of the casualties suffered for little gain other than attrition. John Keegan, one of the leading military historians of his generation, concluded “the point of Passchendaele… defies explanation.” (Keegan, The First World War, p. 394.) 3

The 35th Division Machine Gun Companies, including Bennett’s 106th MGC, remained in Flanders for the remainder of 1917 and into the Spring of 1918. The Divisional MGC’s were involved in some trench warfare in later 1917 as the ground which had been taken had to be held by the British forces. By early January 1918 Bennett was near to Houthhulst Forest, which was the location of fierce fighting in October 1917; an indication of how little progress was being made by the British forces in this war of attrition. There was snow on the ground and strong winds, which at least would ensure that there were fewer impending gas attacks. By early February 1917 Bennett’s Diary tells us that his Division had been in the front line for 17 days, enjoying only 4 days “clear of the line” out of the previous 31 days.

The 35th Division Machine Gun Companies, including Bennett’s 106th MGC, remained in Flanders for the remainder of 1917 and into the Spring of 1918. The Divisional MGC’s were involved in some trench warfare in later 1917 as the ground which had been taken had to be held by the British forces. By early January 1918 Bennett was near to Houthhulst Forest, which was the location of fierce fighting in October 1917; an indication of how little progress was being made by the British forces in this war of attrition. There was snow on the ground and strong winds, which at least would ensure that there were fewer impending gas attacks. By early February 1917 Bennett’s Diary tells us that his Division had been in the front line for 17 days, enjoying only 4 days “clear of the line” out of the previous 31 days.

By mid February 1918 the Germans were still raiding near Passchendaele. Fighting remained intense as the Germans sought to recover lost ground and maintain their lines. On 18th February 1918 Bennett reports from the frontline that “it was the worst fire I have been under.”

The fighting went on into March 1918 and the signs were that little progress had been made by the British or the Germans. On 21st March, Houlthurst Forest was being pounded by British petrol and gas shells. On 22nd March 1918 Bennett received orders that he was about to head south where the German Spring Offensive had begun. The Flanders troops were informed that the Germans, employing tanks equipped with flame throwers, had broken through the British lines and had advanced by more than a mile. The 35th Division with its now combined Machine Gun Company, had orders to get there with all speed.

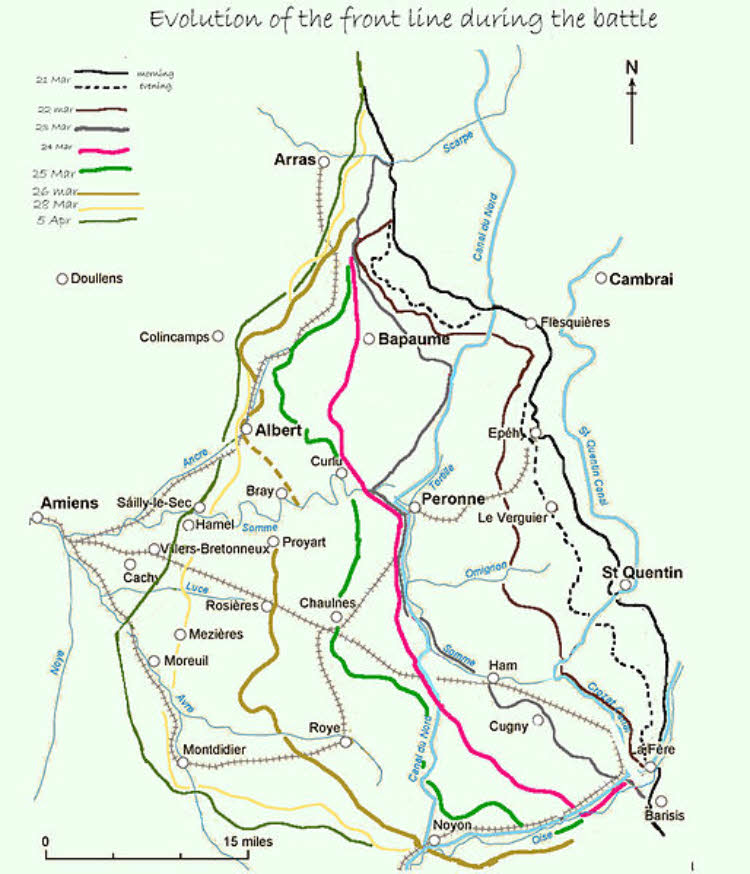

Bennett at the German Spring 1918 Offensive. “The Kaiser’s Battle” March – May 1918

The 1918 Spring Offensive also known as the Kaiser’s Battle or the Ludendorff Offensive, was a series of German attacks along the Western Front beginning on 21 March 1918, which marked the deepest advances by either side since 1914. Its goal was to break through the Allied lines and advance in a north-westerly direction to seize the Channel ports, which supplied the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) and to drive the BEF into the sea. The Germans had realised that their only remaining chance of victory was to defeat the Allies before the USA joined the conflict. They also had the temporary advantage in numbers afforded by the nearly 50 divisions freed by the Russian surrender. The subsequent failure of the offensive marked the beginning of the end of the First World War but some 325,000 Allied troops and 350,000 German troops were killed, wounded or missing in the six weeks to 30 April 1918.

Above: The Spring Offensive front line, 21 March – 5 April 1918.

On the 23rd March 1918 at 4.30 a.m. the 35th Machine Gun Company transferred, 40 to 50 in a cattle truck, from Proven in Belgium Flanders via Calais and Boulogne to Amiens and after a 10 mile march they arrived at Marlicourt at 11.30 p.m. Each of the men had a slice of bread and a cup of tea for the 165 miles journey which had taken 19 hours. The following morning, at 1.30 a.m., the 35th joined forces fighting a rear-guard action on the Somme in the Battle of Bapaume.

The infantry was exhausted and the advance bogged down, as it became increasingly difficult to move artillery and supplies forward to support them over Somme battlefield of 1916. Advancing German troops had also fallen onto the abandoned British supply dumps which caused some demoralisation, when German troops found out that the Allies had plenty of food. By the late evening of the 24th March, after enduring unceasing shelling, Bapaume was evacuated and then occupied by German forces on the following day.

The 35th Division Machine Gun Company Regimental Diary for the 24th March records “C Company marched from Morcourt to Maricourt. Two sections sent to fight rear-guard action with 17th Bn Royal Scots. Remainder of Company withdraw to Carnoy Valley. Later one section with Royal Scots withdraw to Corlu and the other to Carnoy Valley.” Bennett’s Diary adds “We had hardly any food at all today.” The food had all been left behind in the retreat and was now in the hands of the enemy.

On the 25th March the Allied retreat continued with the Regimental Diary indicating “at midnight order received to evacuate positions and retreat to Bray. Rear Btln HQ withdrawn from Bray to Morlancourt.” Bennett reports “fighting very rough. About 11 am Jerry attacked our trenches. Two of our teams were took prisoners and we were nearly surrounded. In getting out we lost all but one gun. Lucky to get out. We were fighting a rear-guard action. I was expecting been took prisoner because I knew Jerry was very close to me.”

The Allied retreat continued through the 26th March and on that night and the morning of the 27th, the French town of Albert fell to the German advance. On 28th March the direction of the German attack focused on Arras but was repulsed. The tide had begun to turn and the 35th MGC regimental Diary records that “C Company remain in occupation of positions to Buire-Dernancourt section.” The last general German attack came on the 30th March and whilst some British ground was lost, the German attack was rapidly losing strength. The Germans had suffered massive casualties during the battle, many to their best units and in some areas the advance slowed, when German troops looted Allied supply depots.

Whilst the worst was over, Bennett was back in the trenches on 4th/5th April and he had this to say: “Jerry made a big attack and pushed the Australians back 300 yards. They (the Australians) inflicted heavy losses on his (the German) troops and took back all they lost. They are fine fellows are the Aussies.”

On the 8th April the 35th MGC and Bennett (of “C” Company) are in the vicinity of Aveluy Wood, when he was in charge of “A” Team in “very muddy awful positions with plenty of machine gun bullets throwing about.” The 35th MGC remained in the Aveluy Wood and Bouzincourt area for the next 10 days or so. Bennett was made Lance Corporal (unpaid) on 17th April.

On 22 April 1918 the Regimental War Diary recorded: “An attack was made by the 35th and 38th to capture high ground East of Bouzincourt and a large portion of Aveluy Wood held by the enemy. 32 guns of A, B & C Companies cooperated with barrages and overhead direct fire. Ammunition was expended as follows:

Bennett’s Diary records the same event in somewhat more florid prose: ”Things pretty lively at dawn. Our fellows and 38th Div made an attack in the evening under a creeping barrage. We put a barrage up with our guns for an hour. It was a fine start, artillery, trench mortars and machine guns all started at the same second. Our position was an absolute hell all night, but we were very lucky. We had no casualties. We were the most lucky section this evening with the shell and machine gun fire he had put on our position. We had no guns damaged every man did well, not a shirker. We were all congratulated by the officer for our fine work. Jerry kept up his heavy fire until 6 am. We fired about 2000 rounds.”

Above: The road up to the Ancre Valley through Aveluy Wood in early 1918.

The action continued in and around Aveluy Wood and Martinsart until late May as the Germans fought to recover lost ground. On the 27th April, Bennett records that “an enemy attack failed” and by the 30th April, the battalion still held all the ground it had held on the 8th April. On the 7th May Bennett was made up to Acting Corporal and on the 11th May, he spent an evening with Ossett born Edward Teale of the 19th Durham Light infantry, which also served in the 35th Division. Sadly, Edward Teale was killed in action on the 1st October 1918.

Simply to occupy a trench of the line in the salient of Ypres during the winter of 1917-1918 was enough to test the nerves of the strongest and bravest. German artillery barrages continually swept the area and were considered by experts to be amongst the heaviest shelling of forward positions ever experienced. The mud and water grew deeper and corpses slowly dissolved and became at one with the elements.4

On the 13th May 1918, two days after his last evening with Edward Teale, Bennett Brook was taken ill with a high temperature, loss of appetite and on the 22 May he was moved to a field hospital. He was subsequently moved to Rouen General Hospital on the 27th May when he records: “German airplanes bombed the town at night.” On the 29th May he was moved by stretcher and hospital train to Le Havre and he arrived in Southampton on the 30th May and later that day he was transported by train to Liverpool . He was transferred by motor to Fazakerley 1st Western Hospital: ”there was a large crowd at the station to watch us of and cheered us as the motors passed by.”

In an undated field card to Mabel (his wife to be) he breaks the news that he is back in the old country and tells her that he is “suffering from Trench Fever but only slight.” It may have been Trench Foot, as reported later in the “Ossett Observer.” In spite of his protestations that he is recovering, he was moved to Whiston Infirmary, Prescott, Liverpool on the 4th June and on 8th June he was visited for the weekend by his mother and Mabel.

“Trench foot” was a fungal infection of the feet brought on by prolonged exposure to damp, cold conditions allied to poor environmental hygiene. Some 20,000 casualties resulting from trench foot were reputed to have been suffered by the British Army alone during the close of 1914. Patients sometimes had to have toes amputated (following gangrene) such were the effects of the condition.5

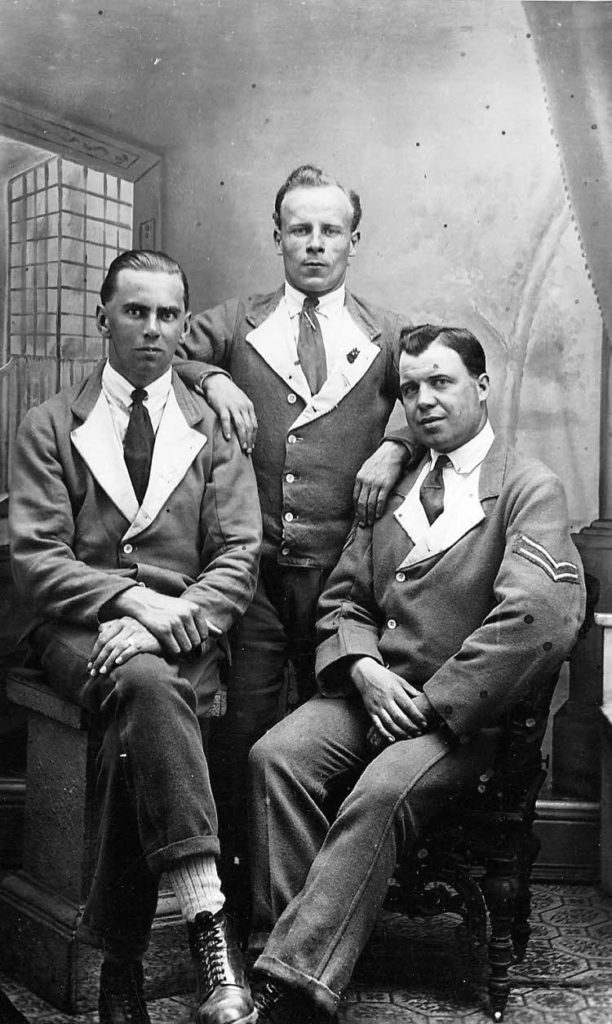

Above: On 16th August 1918, Corporal Bennett Brook (centre) sent this postcard to his future wife Mabel Wormald from Whiston Hospital, Liverpool. He is pictured with two colleagues in hospital garb.

On the 24th August 1918, even though his legs were badly swollen and weak, he was discharged after almost 3 months in the hospital and infirmary. Catching the train from Liverpool, he arrived in Dewsbury at 4pm and made his way home to spend an evening with his family and friends. After ten days at home, on the 3rd September 1918, Bennett took the train from Ossett to Harrowby Camp at Grantham. He was reduced in rank from Corporal to Private and, after seeing the doctor, he was marked Class B3 and transferred to R.D.A. Company. On the 6th September 1918, he was in hospital for a couple of days at Belton Park, Grantham with scabies, before moving back to the Camp where he was to spend many long days on fatigues. On the 22nd September he was marked “B2 for 9 months” by the Medical Board and, a month later, he was still at the Grantham Camp on fatigues.

Shortly afterwards, WW1 ended with the unconditional surrender by the Germans and Bennett returned home to his farming. In spite of his protestations to the contrary his illness must have been serious enough for the Army to keep him hospitalised and in camp for some five months. In January 1920 he was awarded a 30% Disablement Pension of 12 shillings per week. Bennett settled back into the family farming business helping his father around the farm.

In May 1922 Bennett married Mabel Wormald, who he had been courting before the War and with whom he remained in contact whilst serving in France & Flanders. Mabel and Bennett had known each other in their teens and she had visited him during his convalescence and treatment in Military hospitals on his return from the Front. Mabel was employed as an “athletic machinist.” She was the daughter of Joseph Wormald, who ran his photographic business from Dale Street, Ossett. Bennett and Mabel went on to have four children, Dora (born 1924), Bessie ( born 1925), Joyce (born 1926) and David Brook (born 1928).

When Bennett’s father, Fredrick, died in 1936, Bennett took over the business at Sowood Farm and started a Farm Account and Diary Book on the 4th March 1936, the very day of his father’s death. It was as though Bennett wrote a diary to reflect the most stressful and difficult times in his life. Bennett Brook died on the 13th November 1980, aged 89, after suffering a stroke. He was survived by his wife Mabel and his four children. Mabel continued to live at Queen’s Drive, Ossett with her unmarried daughters, Dora and Joyce, until her death, aged 93, in 1987.

References:

1. The National Archives Regimental War Diaries, series WO 95

2. The Long Long Trail The British Army in the Great War of 1914-1918

4. “See How They Ran – The British Retreat of 1918”, William Moore (1970)

Other Sources:

Brook Family records, photographs and personal memories.

“The History of the 35th Division In The Great War”, Lieutenant-Colonel H.M. Davison C.M.G., D.S.O., R.A.

“They Called It Passchendaele: The Story of the Battle of Ypres & of the Men Who Fought in it”, Lyn MacDonald