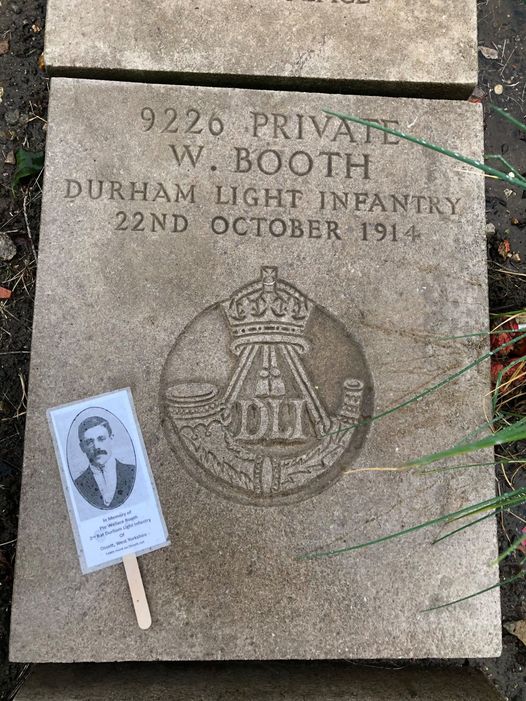

9226, Durham Light Infantry, 2nd Battalion

Wallace Booth was born in Leeds in 1884, the only son of Leeds-born Wallace Booth and his wife Mary Hannah (nee Ball), who married in Leeds in 1873. The Booths had three children in total and Wallace had two sisters. In 1891, Wallace, a shoe-maker, and his family lived on Chickenley Lane Top, but by 1901 they had moved to Wakefield Road, Ossett and Wallace junior now worked as a wool piecer in a local woollen mill.

By 1911, Wallace junior, aged 26, had joined the Regular Army and was a Private soldier in the Durham Light Infantry, stationed in Jullindur, Punjab, India. Wallace Booth’s father, Wallace had fallen on hard times by 1911: his wife of 22 years died in 1904 and in 1911, aged 63, he was an inmate in the Dewsbury Union Workhouse, Healds Road, Dewsbury.

Wallace Booth (21), a warehouseman, enlisted on the 17th August 1905 for nine years in the Colours and three years in the reserve, but his attestation reveals that he already “belonged” to the 1st Battalion, King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry. Wallace was 5’ 4” tall, weighed in at 123 lbs, with a fresh complexion, brown eyes and dark brown hair. He had a scar over his right eyebrow and was tattooed on his left wrist with cross flags, and on his right forearm with a heart and crossed hands.

Declared fit for the army, he joined the 3rd Battalion of the Durham Light Infantry Regiment (D.L.I.) with a service number 9226 and was posted to Newcastle for training on the 19 August 1905. He was subsequently posted to Cork, Ireland in November 1905 until February 1906, when he was posted to the 2nd D.L.I. in Lucknow, India until early January 1909. It was here that he was appointed as an unpaid Lance Corporal in August 1907 but, at his own request, he reverted to the rank of Private in October that year.

In January 1909 he transferred to Nowshera in the Punjab and remained stationed there until January 1913. During his service in India he was hospitalised on several occasions suffering from diseases and infections including gonorrhoea, sand fly fever and malaria. His army conduct sheet had been destroyed in September 1912, but the replacement log recorded only his last entry in 1908, which was for a case of drunkenness.

He had been awarded two good conduct badges during his service and was judged “an excellent soldier in every way.” Wallace completed seven years in India on the 25th February 1913, when he returned home. He married Laura Parkin at St Paul’s Church, Hanging Heaton on the 6th December 1913 whilst on army reserve and working as a warehouseman.

From the 5th August 1914, he was “home” pending deployment until the 7th September 1914. This was the last day he saw his wife and he would never see his child, a son called Wallace, who was born on the 21st October 1914, two days before Wallace Booth died in France. It is unlikely that he ever knew he was a father.

The 2nd Battalion of the Durham Light Infantry was formed in August 1914 at Lichfield as part of 18th Brigade in 6th Division. They moved to Dunfermline, but by the 13th August, the Battalion was at Cambridge engaged in training. On the 10 September 1914 they landed at St. Nazaire and at once moving to reinforce the hard-pressed BEF on the Aisne.

Private Booth was mortally wounded in the Battle of Armentières, one of the actions of the 1st battle of Ypres, between the 13th October and the 2nd November 1914, including the capture of the village of Meteren.

After the Battle of the Aisne, the BEF relocated to the left of the Allied line, to shorten lines of communication with the Channel ports. For the 2nd Battalion, D.L.I. this involved a train journey to Arques in the Ypres sector, via Ciry, Largny and le Meux. On arrival, it marched to Wardrecques where trucks were available to take the men to Hazebrouck. Vieux Berquin, which lies five miles to the east of Hazebrouck, was reached at 14:00 hours on the 13th October 1914. There, the Germans were well ensconced on the east side of a small stream called the Meterenbecque, so the battalion moved to le Verriere to find billets. 1

The 6th Division was tasked to secure a bridge over the River Lys at Sailly-sur-la-Lys, which had to be repaired by engineers before the battalion could cross. On the 17th October it was in the line between Fetus le Touque and le Quesne, just outside Bois-Grenier. A probing attack was launched at la Vallee to determine the enemy’s strength during which Ennetières was taken. The battalion moved into reserve only to be recalled to the frontline on the 20 October, to help deal with a German counter-attack. It is now known that the brigade bore the main weight of German attacks and faced almost a whole army corps during the fighting near Fetus. Not surprisingly, eventually it was overwhelmed with heavy losses. One company lost all but twenty-three ORs. Another lost six killed and forty-eight wounded but, possibly, the greatest loss to the battalion was one hundred and seventy-seven men posted ‘Missing’. This action marked the end of the Battle of Armentières following which the battalion remained in the vicinity of Armentières until May 1915.

On Sunday 18 October 1914, The 2nd Battalion, Sherwood Foresters relieved the 2nd Battalion, Durham Light Infantry in positions at Ennetières. On October 20th 1914, the 2nd Battalion Durham Light Infantry belonged to a reserve force sent to assist the Sherwood Foresters in repulsing a heavy German attack near Ennetières. This action formed a part of the 1st Battle of Ypres which began on the 18th October. Both Battalions suffered heavy casualties that day including many taken prisoner.

The “2nd Battalion, Sherwood Foresters’ War Diary” notes:

“20 October 1914 On night of 19th-20th “A” Company relieved “D” Company, “C” Company relieved “B” Company taking “A” Company’s place in reserve. All night the companies were employed in improving their trenches and communications but the work was considerably interfered with by enemy fire.

At daybreak the enemy commenced a heavy shell fire on the village, the house occupied by Battalion HQ being destroyed. At 7.10am it was reported that a considerable number of the enemy were massing round our right flank towards Escobecques. At 10am “B” Company was sent to reinforce the trenches on the right.

At 11.30am a company of Durham Light Infantry arrived to reinforce the BM. About 1pm a vigorous attack was made on our front trenches, but it was driven off with considerable loss. About 3pm enemy commenced his advance against the right flank supported by artillery from north, east and south. All remaining reserves, 3 platoons of Durham Light Infantry and about 50 men were pushed to aid the 5 platoons who were holding that flank.

The enemy’s advance was however very strong and we were vastly outnumbered. The few remaining men were collected and fell back, some covered the retirement of a battery of our guns and others assisted to man handle the guns onto the road. For some time the remnants of the battalion held on to some high ground overlooking the sandpits west of Ennetières, but at 7pm fell back to the road running through E of Fetus. Here we joined up with the Durham Light Infantry and West Yorkshire Regiments and remained in position until ordered to fall back to Bois Grenier. Casualties 710 NCOs and men missing.”

Private Wallace Booth of the Durham Light Infantry embarked for France on the 9th September 1914. At 3.55 am on the 23rd October 1914, he died of his wounds in no. 13 General Hospital in Boulogne, France. He was 30 years of age, and had been in the regular Army for 9 years and 70 days, including just 46 days in France.

Walllace Booth was awarded the British and Victory medals as well as the 1914 Star with clasp. The 1914 Star, also known as the Mons Star or the Bronze Star was authorised in April, 1917, to be awarded to those who served in France or Belgium between 5th August and midnight on 22nd/23rd November 1914. The former date is the day after Britain’s declaration of war against the Central Powers, and the closing date marks the end of the First Battle of Ypres. Recipients were officers and men of the pre-war British army, specifically the British Expeditionary Force (B.E.F or the Old Contemptibles), who landed in France soon after the outbreak of the War and who took part in the Retreat from Mons, hence the nickname ‘Mons Star’. 365,622 were awarded in total. Recipients of this medal also received the British War Medal and Victory Medal. These three medals were sometimes irreverently referred to as “Pip, Squeak and Wilfred.” Wallace Booth was also awarded the 5th August – 22nd November 1914 Clasp, known as the “Clasp and Roses” and awarded only to those who had operated within range of enemy mobile artillery during this period. When the ribbon bar was worn alone, recipients of the clasp to the medal wore a small silver rosette on the ribbon bar.

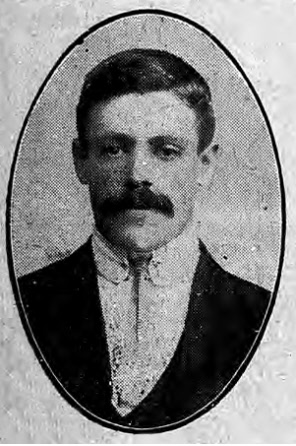

The “Batley News” 2 had this obituary for Private Wallace Booth:

“Infantryman and Notable Athlete Dead – Fatally Wounded in Action – Pathetic Domestic Incident – The name of Private W. Booth, No. 9226, A Durham Light Infantryman, whose wife and child live at Commonside, Hanging Heaton, has to be added to the hillside village’s sad roll of honour; for we regret to announce that official information was received by Mrs. Booth was received on Sunday of “his death on October 23rd from wounds received in action.”

The only son of Mr. Wallace Booth, a respected Ossett native, deceased (though born in Leeds) was brought up in Ossett and spent most of his life there. Thirty years of age, he joined the army seven or eight years ago and left eighteen months before the outbreak of the present war, when he was called up as a Reservist. As a Regular, he saw service in India, and was exceedingly popular with his comrades as an athlete. For long distance running he won several medals and earned other awards as a boxer and a swimmer. On leaving the Army, he was employed by Messrs. J. Fitton, rag merchants, Ossett.

On mobilisation, Private Booth left home at once. His papers received by one morning’s post gave him 12 hours notice, and by noon he was on his way to Newcastle, with Private J. Lyles (a Reservist of the Northumberland Fusiliers) as his travelling companion. After two weeks stay in England, during which time he was stationed both at Newcastle and Cambridge, Booth was drafted across the sea, and his later activities were never definitely intimated by him or the authorities.

After leaving England, Booth sent only one letter home and that showed him to still remain enthusiastic under trying conditions. He stated that the men had plenty of marching, and whilst occasionally snatching an hour or two’s sleep, they were awaken to either go into action or resume their march.

Although not able to write letters, the deceased soldier kept in touch with his wife and relatives by means of the official printed postcard, stating briefly “I am quite well.” The last message of this kind was dated October 17th and nothing further was heard of him until the deplorable news of his death was received from the Infantry Record Office at York.

The deepest sympathy is felt with the deceased relatives, and especially with his wife, formerly Miss Laura Parkin, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. John Parkin of Commonside, Hanging Heaton, who is now the mother of a two-week old child – their only bairn. The sturdy soldier thus never saw the little one, which was born two days before he was killed.”

Wallis Booth’s widow, Laura, of 33, Lucas St Buildings Common Side, Hanging Heaton was granted a separation allowance of 12/6d a week from the 1st November 1914 and from the 2nd May 1915 a pension of 15/- a week. In July 1919, she was required to make a return of the close relations of her deceased husband. This recorded a son, Wallace Booth, born 21st October 1914 and a sister, Minnie Booth, aged 34, who lived at 18, Cross Flatts Avenue, Dewsbury. Wallis’s mother had died in 1904 and his father, Wallace, was in the Staincliffe Institution Dewsbury (formerly Dewsbury Union Workhouse) where he died in 1924.

Above: The village of Ennetières scene of fierce fighting in October 1914 when the 2nd Battalion Sherwood Foresters were virtually wiped out and the 2nd Battalion, Durham Light Infantry also suffered heavy casualties. It is thought that Private Wallace Booth was mortally wounded near here on the 20th October 1914.

Private Wallace Booth was killed in action, aged 31 years, on the 23rd October 1914, and he is buried at grave reference III. A. 2. at the Boulogne Eastern Cemetery, 3 Pas de Calais, France. Boulogne-sur-Mer is a large Channel port. Boulogne Eastern Cemetery, one of the town cemeteries, lies in the district of St Martin Boulogne, just beyond the eastern (Chateau) corner of the Citadel (Haute-Ville).

The cemetery is a large civil cemetery, split in two by the Rue de Dringhen, just south of the main road (RN42) to St Omer. The Commonwealth War Graves plot is located down the western edge of the southern section of the cemetery, with an entrance in the Rue de Dringhen. Unusually, the headstones are laid flat in this cemetery. This is due to the sandy soil.

Boulogne, was one of the three base ports most extensively used by the Commonwealth armies on the Western Front throughout the First World War. It was closed and cleared on the 27 August 1914 when the Allies were forced to fall back ahead of the German advance, but was opened again in October and from that month to the end of the war, Boulogne and Wimereux formed one of the chief hospital areas.

Until June 1918, the dead from the hospitals at Boulogne itself were buried in the Cimetiere de L’Est, one of the town cemeteries, the Commonwealth graves forming a long, narrow strip along the right hand edge of the cemetery. In the spring of 1918, it was found that space was running short in the Eastern Cemetery in spite of repeated extensions to the south, and the site of the new cemetery at Terlincthun was chosen.

During the Second World War, hospitals were again posted to Boulogne for a short time in May 1940. The town was taken by the Germans at the end of that month and remained in their hands until recaptured by the Canadians on 22 September 1944.

Boulogne Eastern Cemetery contains 5,577 Commonwealth burials of the First World War and 224 from the Second World War.

Commonwealth War Graves Commission Headstone (Photograph courtesy of Mark Smith)

References:

1. A short history of the 6th Division Aug. 1914- March 1919 (1920)

2. “Batley News”, 7th November 1914