Rowland Saxton was born in Ossett in early 1896, eldest of six children born to George Henry Saxton and his wife Hannah (nee Robinson) who married in Spring 1894. One of their children died before April 1911.

In 1901, Rowland was living with his married mother and his younger sister, Gertrude, on Chancery Lane, Ossett. His father, George, is not recorded in the household. They left Ossett shortly after 1901 and by 1911 the family were living in Batley where Rowland was working as a cloth finisher for a woollen manufacturer.

Rowland Saxton’s army service record has not survived, but it is known that he enlisted in Batley and joined the King’s Royal Rifle Corps, with regimental service number R/16863, before transferring to the Machine Gun Corps, MGC, (service number 29364). Gunner R. Saxton was serving with the 160th Company M.G.C. when he was killed in action on the 7th November 1917. He was 21 years of age and was posthumously awarded the British and Victory medals, but not the 1914/15 Star indicating that he did not serve before 31st December 1917.

The 160th Machine Gun Company was formed in the 53rd (Welsh) Division on the 11th May 1916. Rowland Saxton was killed during the Battle of Tell Khuweilfe between the 3rd and 7th November 1917, a prelude to the capture of Gaza and Jerusalem from the defending Turkish Ottoman Empire. Tel el Khuweilfe, was a Turkish strongpoint with a good water supply, ten miles north of Beersheba. The British then had to tackle the enemy who still held Khuweilfe. This was rough, dry country and the summer lingered on with intense heat and a three-day khamsin.

There was no water to be had beyond Beersheba and the infantrymen, Yeomanry and Light Horse had to march and fight on one water bottle in 36 hours, and the horses on nothing – they would not eat past the early stages of thirst – until they could be brought out of action and back to Beersheba, twelve to fifteen miles away. Tel el Khuweilfe commanded the country to both west and east, and would therefore menace the British infantry and mounted troops when they struck at the Hareira and Nejile redoubts in the rolling-up process. On the other hand, its capture by the British would leave the Turkish left flank in the air.

The 158th Brigade of the 53rd Division set off before dawn on the 6th November to attack Tel el Khuweilfe, unfortunately short of one battalion that had not arrived in time. During the attack, which took place in a very heavy mist, British artillery accidentally shelled the closing British forces and much confusion ensued with many casualties from Turkish machine gun fire from the hill top. Shortly before dawn on the 7th November, the machine-gunners were withdrawn, but the fire fights resumed with daylight, Turkish close-range sniping especially taking a severe toll. The action was deadlocked, with the Camels and 53rd units unable to move, and the Turks held at bay. The Turks that day fought with exceptional resolution and savagery, and British and Australian wounded and stretcher-bearers were repeatedly fired upon.

At 3 p.m., accurate artillery fire was brought to the support of the 53rd, enabling a general advance to be mounted towards evening. All troops had been marching and fighting for over 36 hours, but summoned their last reserves to attack determinedly. The Camels rushed the slopes of Khuweilfe with bayonets and hand grenades, and after brief resistance the Turks fled the grim mound. The 53rd went forward until darkness checked them. The night was tense but quiet, and in the morning it was found that the Turks, whose front had been comprehensively breached by Chetwode at Kauwukah, had abandoned all the Khuweilfe fortifications.

Khuweilfe was a piecemeal, reactive action. It seemed small scale, undeserving of proper plans and systematic reduction, yet the pinprick became a consuming canker that wore down and mauled three divisions for six days. In the final action, the 53rd Division suffered the heaviest pro rata casualties, including Private Rowland Saxton.

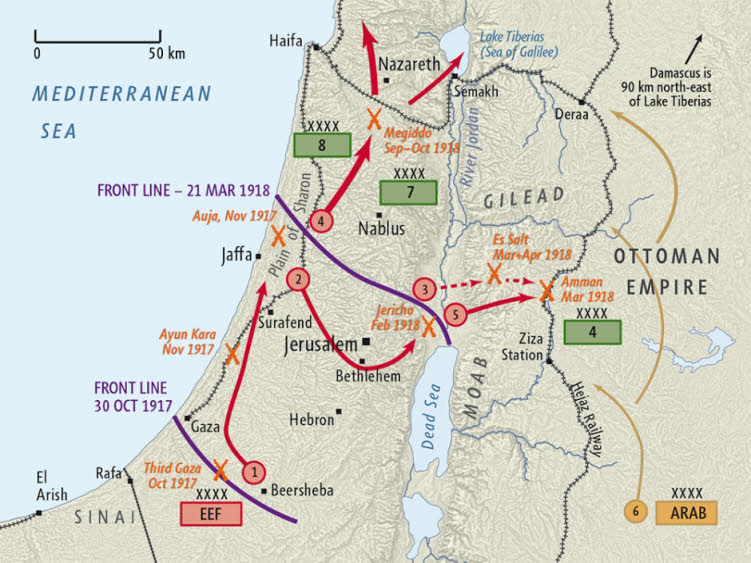

Above: Map showing the Allied Palestine Campaign in 1917/18.

There was a short obituary for Rowland Saxton in the “Batley News”,1 which provides us with a bit more information:

“Saxton – In ever loving memory of our dear son and brother, Private Rowland Saxton, MGC, killed in action in Palestine, November 7th 1917, aged 21 years.

“One of the bravest, one of the best,

Doing his duty, he was called to rest,

‘Thy will be done’, tis hard to say.

When one we loved is called away.Some day we hope to meet him,

Some day, we know not when.

To clasp his hand in the better hand,

Never to part again.”From his loving father, mother, sister and brothers, 18, Providence Street, Batley.“

Rowland Saxton is not recorded on any Ossett Memorial or Roll of Honour probably because his he and his family left Ossett shortly after 1901. He is remembered in this 2014 biography and Roll of Honour because the Commonwealth War Graves Commission and/or the “U.K. Soldiers who Died in the Great War 1914-1918” listing records him as born or residing in Ossett.

Private Rowland Saxton, son of George Henry and Hannah Saxton, of 18, Providence St., Batley, Yorkshire, died aged 21 years, on the 7th November 1917 and is remembered on Panel 55 at the Jerusalem Memorial,2 Israel and Palestine (including Gaza). The Jerusalem Memorial stands in Jerusalem War Cemetery, 4.5 kilometres north of the walled city and is situated on the neck of land at the north end of the Mount of Olives, to the west of Mount Scopus.

At the outbreak of the First World War, Palestine (now Israel) was part of the Turkish Empire and it was not entered by Allied forces until December 1916. The advance to Jerusalem took a further year, but from 1914 to December 1917, about 250 Commonwealth prisoners of war were buried in the German and Anglo-German cemeteries of the city.

By 21 November 1917, the Egyptian Expeditionary Force had gained a line about five kilometres west of Jerusalem, but the city was deliberately spared bombardment and direct attack. Very severe fighting followed, lasting until the evening of 8 December, when the 53rd (Welsh) Division on the south, and the 60th (London) and 74th (Yeomanry) Divisions on the west, had captured all the city’s prepared defences. Turkish forces left Jerusalem throughout that night and in the morning of 9 December, the Mayor came to the Allied lines with the Turkish Governor’s letter of surrender. Jerusalem was occupied that day and on 11 December, General Allenby formally entered the city, followed by representatives of France and Italy.

Meanwhile, the 60th Division pushed across the road to Nablus, and the 53rd across the eastern road. From 26 to 30 December, severe fighting took place to the north and east of the city but it remained in Allied hands.

Jerusalem War Cemetery was begun after the occupation of the city, with 270 burials. It was later enlarged to take graves from the battlefields and smaller cemeteries in the neighbourhood.

There are now 2,514 Commonwealth burials of the First World War in the cemetery, 100 of them unidentified.

Within the cemetery stands the Jerusalem Memorial, commemorating 3,300 Commonwealth servicemen who died during the First World War in operations in Egypt or Palestine and who have no known grave.

References:

1. “Batley News”, 9th November 1918