John Smith was born in Manchester about 1880 and may have originated from the Miles Platting, Newton Heath area of the city, which was, at that time, incorporated in the Prestwich registration district. John Smith married Lilian Brown in summer 1901 in the same part of Manchester and the couple had three children, Amy (born March 13th 1902), Edith (born 1904-05) and Arthur (born 1906-07) all of whose births were registered in the same Prestwich district.

It has not been possible with any accuracy to discover the names of John’s parents or of his whereabouts between the year of his birth and 1901. It is known that he moved to Ossett after 1907 and by 1911 he was living at 7, Chancery Lane with his wife Lillian and their three surviving children of five born to the marriage. John was working as a hewer in a local pit.

John Smith’s army service record appears not to have survived but it is known that he enlisted in Dewsbury when, unsurprisingly, he was posted to the 12th Battalion King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry (Miners) (Pioneers) Regiment; also known as “t’owd twelfth”.

The history of the 12th Service Battalion (Miners)(Pioneers) King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry dates from the 5th September 1914 when the War Office authorised the West Yorkshire Coalowners Association to raise a Miners Battalion for the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry (KOYLI) . After beginning its life at Leeds, the battalion trained first at Farnley Park, Otley and then at Burton Leonard, near Ripon. By this time it had been allocated to 31st Division as its pioneer battalion. After completing its training in Yorkshire, the battalion moved to Fovant, Salisbury in October 1915 before embarking for Egypt on 6th December. After little more than two months in Egypt, the 12th K.O.Y.L.I. was ordered to France in March 1916 to take part in the planned summer offensive on the Somme.

An early solution to the vast demand for labour to support the war effort was to create in each infantry Division a battalion that would be trained and capable of fighting as infantry, but that would normally be engaged on labouring work. They were given the name of “Pioneers”. They differed from normal infantry in that they would be composed of a mixture of men who were experienced with picks and shovels (i.e. miners, road men, etc) and some who had skilled trades (smiths, carpenters, joiners, bricklayers, masons, tinsmiths, engine drivers and fitters). A Pioneer battalion would also carry a range of technical stores that infantry would not. This type of battalion came into being with an Army Order in December 1914. In early 1916, a number of infantry battalions composed of men who were medically graded unfit for the fighting were formed for labouring work. They had only 2 officers per battalion. Twelve such battalions existed in June 1916.

Because his army service record has not survived it is not possible with any certainty to determine the precise date when he enlisted, at Dewsbury. A comparison of his service number, 12/1063, with other men whose 12th battalion K.O.Y.L.I. service records have survived indicate that he may have enlisted in spring 1915.

His Medal Index Card indicates that he embarked for Egypt on the 22nd December 1915 some two weeks or so after the 12th battalion King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry left for Egypt on the 6th December 1915. After little more than two months in Egypt, the 12th K.O.Y.L.I. was ordered to France in March 1916 to take part in the planned summer offensive on the Somme.

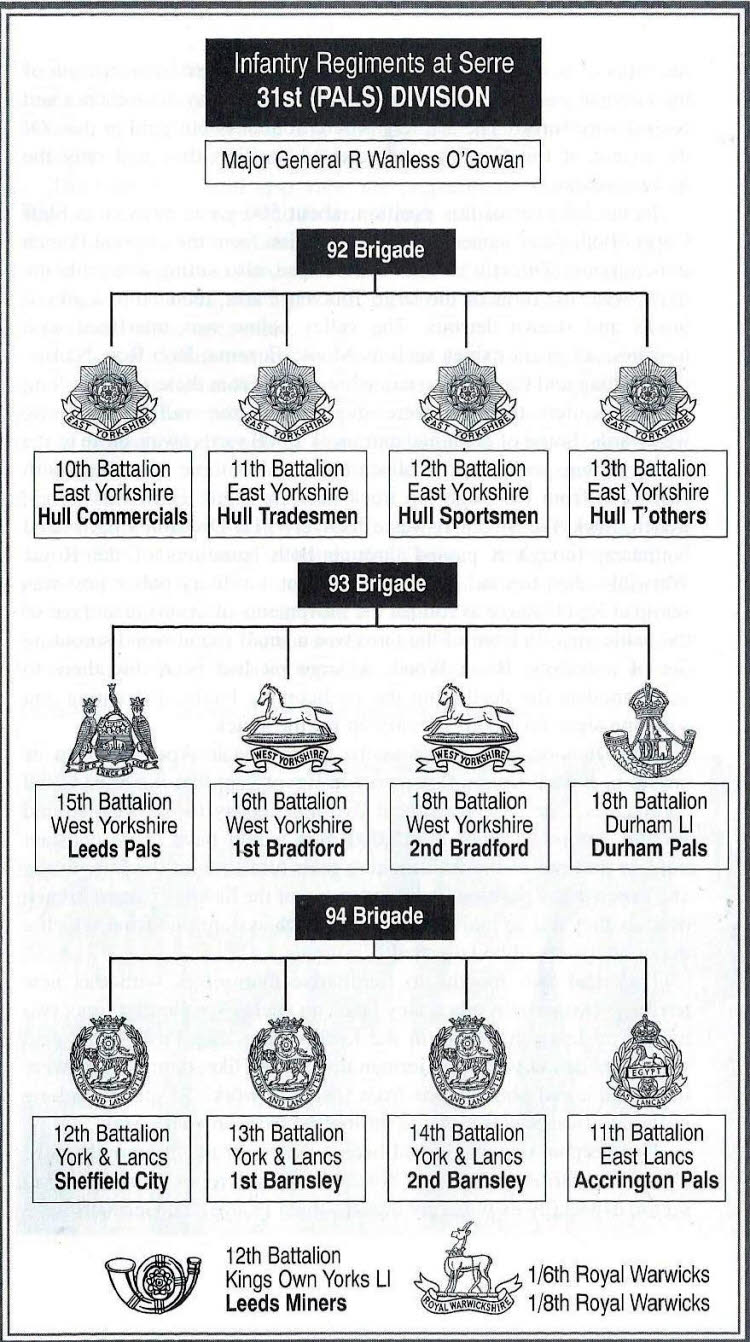

On 1st July 1916 the 12th KOYLI were part of the 31st (Pals) Division which included the Leeds, Bradford, Sheffield, Barnsley, Hull, Durham and Accrington Pals. 1st July 1916, was the first day of The Battle of The Somme when the British forces suffered 57,470 casualties, including 19,240 fatalities. In a single day.

The following words about this day and the “t’owd twelfth” are reproduced from The History of The King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry In The Great War 1914-1918 by Lt-Col.Reginald C. Bond, D.S.O.

“Lt-Col E.L.Chambers was in command of the battalion whose HQ was in Bus-les-Artois, about 10 miles north of Albert. By the 20th June 1916 preparations for the attack on the German line were in full swing in the division, and the companies of the Pioneer battalion were allotted: Company “A” to the 94th Infantry Brigade, Company “D” to the 93rd, while Companies “B” and “C” were detailed for work connected with clearing out the German communication trenches leading to the line which it was hoped to capture in the first bound.

When a division entered upon a general attack, there was no vast distinction made between an infantry soldier and a pioneer infantry man; the ordinary soldier carried 220 rounds of ammunition, the pioneer carried 170 rounds plus a pick or a shovel; their other impediments were very much the same in detail.

The troops of the division allotted to the successive waves wore distinguishing strips of coloured cloth tied to the right shoulder strap. This practice was universally adopted at this period of the war and ensured that each individual knew the objective which he was to reach during the course of the attack. The successive waves passed through each other, and thus the objectives which were first captured were consolidated, while fresh troops went forward to the later objectives.

At 5.50 am on the 1st July all companies were present in their assembly posts. The official account of the 12th battalion’s experiences written in their regimental war diary for 1st July 1916 simply states:

‘Battalion reported present in assembly posts at 5.50am Battalion reassembled at assembly posts at 4.30pm Casualties sustained: 1 officer killed, 3 wounded, 188 other ranks killed and wounded.’

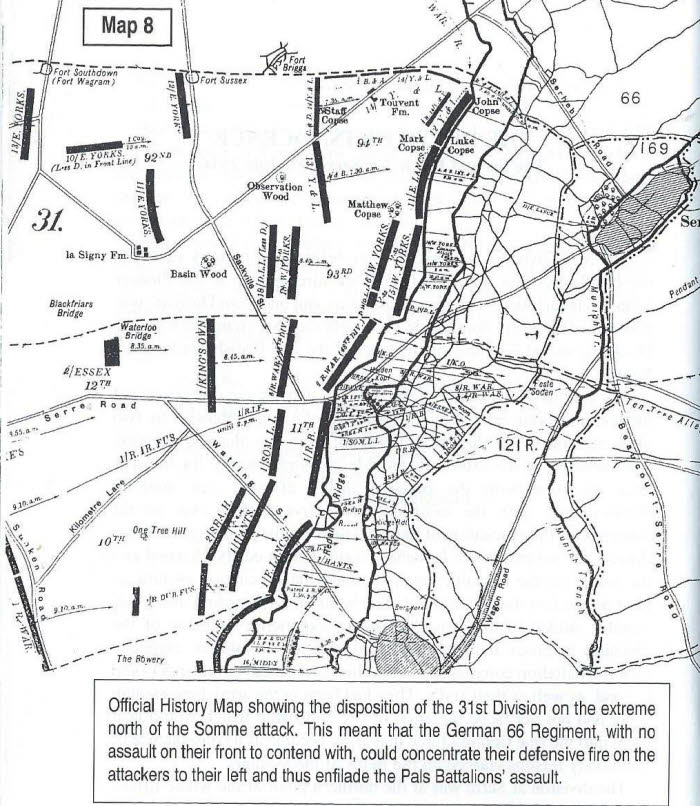

Such a diary demands amplification for this record. The 94th and 93rd Infantry Brigades, to which “A” and “D” companies of the 12th battalion were allotted in the attack had Serre for their objectives. At 7.30 the whistles blew; each brigade went over the top in waves on a front of two companies; the left brigade of the Fourth Army was the 94th Infantry Brigade. They were met by a destructive fire from the German infantry (who had been sheltered from our artillery barrage), from numerous machine-guns, and, most serious of all, from an immense concentration of heavy guns, especially from the direction of Bucquoy, east of Hebuterne, on their left front.

To quote Conan Doyle:

“These guns formed successive lines of barrage with shrapnel and high explosives one of them being about 200 yards behind the British line, to cut off the supports; another 50 yards behind ; another 50 yards in front; and a fourth of shrapnel which was under observed control, and followed the troops in their movements. The advanced lines of assault were able in most cases to get through before these barrages were effectively established, but they made it difficult, deadly, and often impossible, for the lines who then followed.

The companies of the 12th K.O.Y.L.I. had their duties to perform among “the lines who then followed.”

The waves of the attack melted under the hail of metal; they advanced at the only pace they were permitted – the quick time, never the double. Those “who followed” had to rebuild trenches that were crumbling under heavy gunfire, forward supplies of ammunition, dig new trenches, and help in the later hours to save some of the wounded. That these duties did not render them immune from danger to life is obvious from their casualty list: that they found opportunities of displaying high military qualities….“

The following extracts are taken from The Battleground Europe series “Somme Serre” by Jack Horsfall & Nigel Cave:

“Dispersed amongst all the battalions in both brigades were 12/KOYLI (T’Owd Twelfth) mainly miners and many from Charlesworth Pit who had streamed into Leeds from the surrounding villages in 1914.Whole shifts marched together to enlist, shepherded in by regular sergeants in uniform who coaxed others out of the pubs as they went, until eventually arriving at the railway station to be put on board trains taking them into Farnley Camp at Otley. These men’s heroic but unsung tasks was to suffer the annihilating bombardment and machine gun fire of the Germans while rebuilding shattered trenches and bridges and keeping the communication trenches clear of the awful obstructions brought about by the atrocious weight of the shelling. They had to bring out the wounded clear those who had died and bury many on the spot on the trench floor. They had to fetch and carry barbed wire, stakes, water, food and anything that was required by the infantrymen, such as ammunition, grenades and mortar bombs- the whole without any opportunity of their own to have a go at the enemy.

“C” Company and three platoons of “B” Company from 12/KOYLI the Pioneers battalion, had gone into action with 93 Brigade. They had worked like demons in supporting and succouring their battered comrades. They made endless , blood soaked journeys back and forth with dead and wounded; they had re-dug, shored up and cleared collapsed trenches and dugouts; they had buried remains of men in the bottom of trenches and all the while had to do this under a rain of death falling about them.

At mid-morning, because the Pioneers were the only battalion resembling a coherent force, they were ordered to act as infantry in the face of the expected German attack and took up defensive positions along the Divisions right boundary in Sackville Street. It was here that the remnants of 12/KOYLI were positioned to form a defensive line facing Serre in case of a German counter attack.

…..the divisional pioneers had lost 192 – men who were not there to fight with anything more offensive than a shovel had lost a third of their complement.”

And so it was that Private 12/1063 John Smith met his death on the first day of 1st July 1916, the first day of The Battle of The Somme. The bloodiest day in British military history. The day when the British forces suffered 57,470 casualties, including 19,240 fatalities. By way of context, should it be needed, the population of Ossett in 1911 was 14,078.

He was posthumously awarded the British and the Victory medals for his service overseas in a theatre of war. His relatively short service in Egypt before the 31st December 1915 also qualified him for the award of the 1914-1915 Star Medal.

Private John Smith, service number 12/1063, 12th Battalion, King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry was killed in action on July 1st 1916. He is buried at Euston Road Cemetery, Colincamps, Somme, France at cemetery reference I.D.17. Colincamps is a village 11 kilometres north of Albert.

Colincamps and “Euston”, a road junction a little east of the village, were within the Allied lines before the Somme offensive of July 1916. The cemetery was started as a front line burial ground during and after the unsuccessful attack on Serre on 1 July, but after the German withdrawal to the Hindenburg Line in March 1917 it was scarcely used. It was briefly in German hands towards the end of March 1918, when it marked the limit of the German advance, but the line was held and pushed forward by the New Zealand Division allowing the cemetery to be used again for burials in April and May 1918.

The cemetery is particularly associated with three dates and engagements; the attack on Serre on 1 July 1916; the capture of Beaumont-Hamel on 13 November 1916; and the German attack on the 3rd New Zealand (Rifle) Brigade trenches before Colincamps on 5 April 1918. The whole of Plot I, except five graves in the last row, represents the original cemetery of 501 graves. After the Armistice, more than 750 graves were brought in from the surrounding battlefields and other small cemeteries.

The UK Army Register of Soldiers’ Effects reveals that Private John Smith’s unspent army pay and allowances of £3 8s 3d was left to his widow and sole legatee, Lilian Smith in October 1916. A War Gratuity of £7 was also paid to her in July 1919.

John Smith was not remembered on any Ossett Roll of Honour or Memorial and neither has an Ossett Observer obituary for him been discovered. Private John Smith will be remembered on November 11th 2018 when his name, engraved at the Ossett War Memorial in the Market Place, will be unveiled.

CWGC heastone photograph courtesy of Mark Smith

References:

1. “Serre Somme” by Jack Horsfall & Nigel Cave Battleground Europe ISBN 0 85052 508 X

2. “The History of The King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry In The Great War 1914-1918” by Lt-Col. Reginald C. Bond, D.S.O.

3. Edgar Pickles, Another Ossett man who served in 12th KOYLI and who died of his wounds on July 2nd 1916.