James Henry Matthews was born in Bradford in September 1895, the second child and second son of five children, all born in Bradford between 1894 and 1900, to James Henry Matthews, a wood turner and his wife Rose Ann (nee Conlan) who were married in 1895. Unusually, for the time, the couple already had two children before they were married.

In 1901, the Matthews children were, Walter (born June quarter of 1895); James Henry (born June quarter of 1895), but showing different ages of 6 years and 5 years respectively, plus William (born March 1900). There was no record in 1901 of the other two children, John and Nellie Matthews. At the time of the 1901 census, the Matthews family were living in Bradford, but sadly, Rose Ann died in Bradford in late 1906, aged 32, leaving James Henry senior a widower with five children, all under the age of 12 years. It isn’t clear if all the children were theirs or if some were adopted.

By 1911, Nellie has become Eleanor Matthews, John has become Albert Edward Matthews and Walter has left home. The Matthews family have now moved to 21, George Street, Horbury where James Henry, aged 15, was working as an apprentice wood turner. His grandfather, also James Henry, a former joiner, is also living with the family.

Sometime after 1911 the family had moved to Belmont House, The Green, Ossett and at the age of 20 years and three months on the 5th December 1915, James Henry Matthews enlisted at Ossett and joined the Durham Light Infantry. He was unmarried, 5’ 1½” tall, weighed 114 lbs, with a 35” chest measurement and his overall physical development was classed as ‘satisfactory’. He gave his home address as Belmont House, The Green, Ossett and was immediately posted to the Army reserve until mobilised on the 6th June 1916, when he was posted to the 23rd Durham Light Infantry, and after four months training, he embarked for France on the 14th October 1916 when his service no. was 23/315.

The 23rd (Reserve) Battalion of the Durham Light Infantry was formed at Catterick in October 1915 from depot companies of the 19th Battalion. They moved to Atwick near Hornsea in April 1916 and on the 1st September 1916, the Battalion was absorbed into Training Reserve Battalions in 20th Reserve Brigade at Hornsea.

On the 27th October 1916, he was posted to the 10th Battalion, Durham Light Infantry in the field. The 10th (Service) Battalion came under orders of 43rd Brigade in the 14th (Light) Division. Private James Henry Matthews was reported missing on the 23rd August 1917 but, subsequently, a comrade confirmed to his superior officer that he had seen him killed in action.

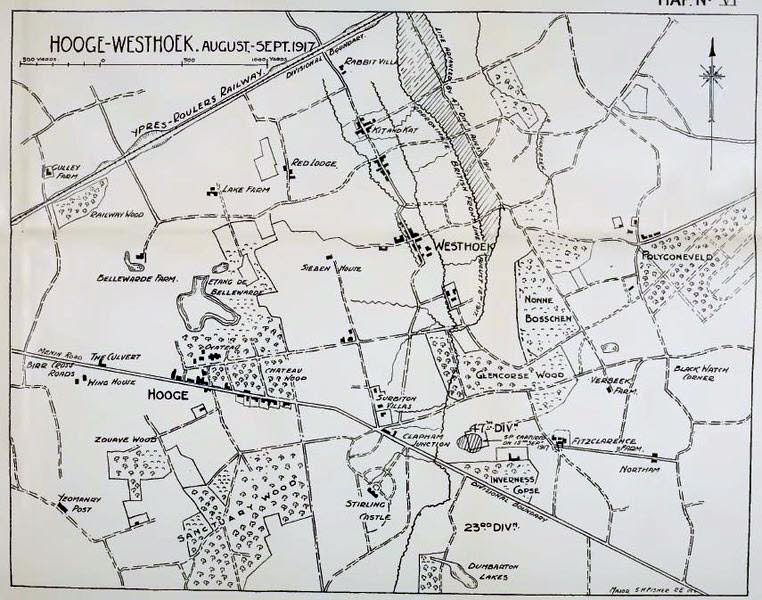

The Battle of Langemarck from 16th to the 18th August 1917, was the second Allied general attack of the Third Battle of Ypres during the First World War. The battle took place near Ypres in Belgian Flanders on the Western Front. After the main battle, there were a number of minor operations, including one on the 22nd August at Hooge and Westhoek that cost Private James H. Matthews his life.

The 10th Battalion, Durham Light Infantry moved to Zillebeke bund (Passchendaele) on the 20th August 1917, before entering Sanctuary Wood two days later, participating in the attack on Herenthage Chateau later that day when 50 Germans were killed. The objective was Inverness Copse, which was reached but not held. There was a German counter attack on the 24th and the 10th Battalion was withdrawn on the 25th, having lost 14 officers and 355 other ranks in what was actually a costly and significant event.

“On 22 August the 24th Division captured a strong point near Bodmin Copse and the II Corps resumed operations to capture Nonne Bosschen, Glencorse Wood and Inverness Copse astride the Menin Road, the copse and Herenthage Park being the first objective. The German outpost line was back on the western edge of the copse, about 600 yards (550 m) west of the Albrecht (second) line. The 14th Division with four tanks, forced the German defenders back to the Albrecht line, with heavy losses to both sides. The dry lake beds due west of Herenthage Château and the Château were captured with 50 prisoners; north of the Menin road the attackers occupied Inverness Copse but failed to reach Jap Trench, after the left battalion was held up at the first objective. The rest of the brigade withdrew to the middle of the copse and called for reinforcements.” 1

Above: Sanctuary Wood and Inverness Copse, south of Hooge, where Private James H. Matthews lost his life on the 23rd August 1917.

The “Ossett Observer” 2 had this short obituary for Private Matthews:

“After taking part with engagements with the enemy on August 23rd last year, Private James Henry Matthews (22), of the Machine-Gun Corps; whose father resides at Belmont House, the Green, Ossett, was posted as missing from his regiment. Since then nothing has been discovered of the missing soldier and this week his father has received and official intimation from Army headquarters stating that the authorities are constrained to conclude that the soldier had met with his death. Private Matthews used to work as a wood-turner at Messrs. Sykes’ athletic goods factory, Horbury. He had been at the front close upon twelve months.”

Private Matthew’s army service record has not survived, but he was awarded the British and Victory medals, but not the 1914-15 Star indicating that he did not serve overseas before 31 December 1915.

In 1919 the Army requested the usual information in respect of the close relatives of the deceased soldier and his father confirmed that James Henry’s mother had died and that he had two brothers: Albert Edward Matthews aged 22 and William Matthews aged 19. No mention is made of a sister.

Private James Mathews was killed in action, aged 22 years, on the 23rd August 1917, the son of widower James Henry Mathews, of Belmont House, The Green, Ossett. His body was never recovered and he is remembered on Panel 128 to 131 and 162 and 162A at the Tyne Cot Memorial, 3 Zonnebeke, West-Vlaanderen, Belgium. The Tyne Cot Memorial to the Missing forms the north-eastern boundary of Tyne Cot Cemetery, which is located 9 kilometres north east of Ieper town centre, on the Tynecotstraat, a road leading from the Zonnebeekseweg (N332). The names of those from United Kingdom units are inscribed on Panels arranged by Regiment under their respective Ranks.

The Tyne Cot Memorial is one of four memorials to the missing in Belgian Flanders which cover the area known as the Ypres Salient. Broadly speaking, the Salient stretched from Langemarck in the north to the northern edge in Ploegsteert Wood in the south, but it varied in area and shape throughout the war.

The Salient was formed during the First Battle of Ypres in October and November 1914, when a small British Expeditionary Force succeeded in securing the town before the onset of winter, pushing the German forces back to the Passchendaele Ridge. The Second Battle of Ypres began in April 1915 when the Germans released poison gas into the Allied lines north of Ypres. This was the first time gas had been used by either side and the violence of the attack forced an Allied withdrawal and a shortening of the line of defence.

There was little more significant activity on this front until 1917, when in the Third Battle of Ypres an offensive was mounted by Commonwealth forces to divert German attention from a weakened French front further south. The initial attempt in June to dislodge the Germans from the Messines Ridge was a complete success, but the main assault north-eastward, which began at the end of July, quickly became a dogged struggle against determined opposition and the rapidly deteriorating weather. The campaign finally came to a close in November with the capture of Passchendaele.

The German offensive of March 1918 met with some initial success, but was eventually checked and repulsed in a combined effort by the Allies in September.

The battles of the Ypres Salient claimed many lives on both sides and it quickly became clear that the commemoration of members of the Commonwealth forces with no known grave would have to be divided between several different sites.

The site of the Menin Gate was chosen because of the hundreds of thousands of men who passed through it on their way to the battlefields. It commemorates those of all Commonwealth nations, except New Zealand, who died in the Salient, in the case of United Kingdom casualties before 16 August 1917 (with some exceptions). Those United Kingdom and New Zealand servicemen who died after that date are named on the memorial at Tyne Cot, a site which marks the furthest point reached by Commonwealth forces in Belgium until nearly the end of the war. Other New Zealand casualties are commemorated on memorials at Buttes New British Cemetery and Messines Ridge British Cemetery.

The Tyne Cot Memorial now bears the names of almost 35,000 officers and men whose graves are not known. The memorial, designed by Sir Herbert Baker with sculpture by Joseph Armitage and F.V. Blundstone, was unveiled by Sir Gilbert Dyett on 20 June 1927. The memorial forms the north-eastern boundary of Tyne Cot Cemetery, which was established around a captured German blockhouse or pill-box used as an advanced dressing station. The original battlefield cemetery of 343 graves was greatly enlarged after the Armistice when remains were brought in from the battlefields of Passchendaele and Langemarck, and from a few small burial grounds. It is now the largest Commonwealth war cemetery in the world in terms of burials. At the suggestion of King George V, who visited the cemetery in 1922, the Cross of Sacrifice was placed on the original large pill-box. There are three other pill-boxes in the cemetery.

There are now 11,956 Commonwealth servicemen of the First World War buried or commemorated in Tyne Cot Cemetery, 8,369 of these are unidentified.

References:

1. Battle of Langemarck (1917)

2. “Ossett Observer”, 22nd June 1918