James Erly was born in Ossett in late 1882, the son of James Erly, from Sligo, Ireland and his wife Margaret (nee Moran) who had married in Wakefield in 1871. Both James and Margaret Erly left Ireland in the late 1860s or early 1870s to make a new life in England. James junior was on of ten children born to the couple. In 1881, the Erly family were living on Horbury Road in Ossett and by 1891, the family have moved to Crown Street in Ossett.

In 1901, the Erly family were living on Manor Road, Ossett and James’ father was working as a mill hand, most probably at nearby Manor Mill. At that time, 19 year-old James was employed as a coal miner and five of his siblings, aged between 5 and 23 years were still living at home. James’ father died in early 1910 and sadly, two of the Erly child en had died before 1911. In that year, James was 29 years of age and was working as a football stitcher. He was living with his 60 year-old widowed mother Margaret, who had been born in Galway, Ireland in a two-roomed house in Victoria Street, Ossett. Also living at the same address in 1911 were James’ brother, Joseph (22) and their sister Margaret (26), both working in the rag trade.

On the 11th November 1901, James Erly enlisted in the British Army at Leeds, joining the Northumberland Fusiliers, service number 8271. His army record survives from 1901 in which he is described as 19 years and 4 months old, a labourer, 5ft 5 and 5/8″ in height, 127 lbs in weight, chest size, 32″ – 34″, dark complexion, grey eyes, dark brown hair and his only distinctive mark was a mole on the right shoulder. He was declared fit for army service and was posted to barracks in Northumberland shortly afterwards. His given address was 11, Albert Street, Ossett and his next of kin, his father James Erly at 55, Manor Road, Ossett.

James Erly saw service in Antigua in the West Indies for 84 days between April and July 1902. He was then sent to South Africa after the end of the Second Boer War (11th October 1899 – 31st May 1902), arriving there on the 23rd July 1902. Private Erly stayed in South Africa for over four years before returning home to England on the 5th March 1907. He was back in England with the Regiment for nearly three years before being placed on the Reserve List in November 1911 for four years, until November 1913.

During his time with the 3rd Battalion, Northumberland Fusiliers, between 1902 and 1909, Private James Erly seems to have done well and he learned how to be a skilled horse rider as a mounted infantry man. His character is described as “good” with the award of a 3rd Class Certificate of Education in April 1902 and passes in “Mounted Infantry” in 1903 and 1907, the latter when he was described as “very good”. There was only one minor blemish on his record and this occurred in May 1904 when he was “tried and convicted by DCM (District Court Martial) of using threatening language to his superior officer” for which he was placed in confinement for 9 days prior to the court martial and another 28 days afterwards. He was relieved of his “Good Conduct” badge, but won it back a year later and won another one in 1907.

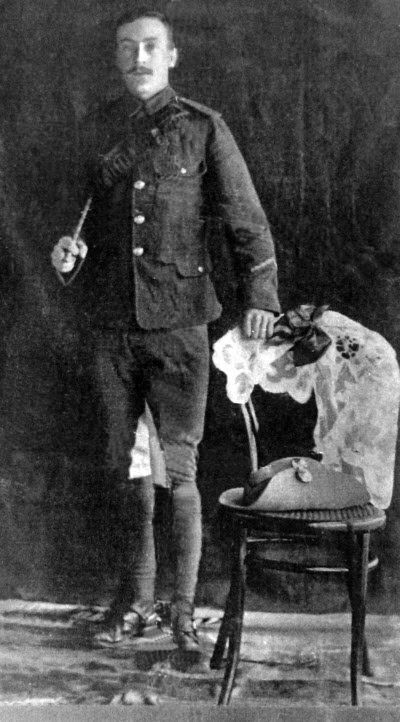

Above: James Erly circa 1905 when he was serving in South Africa with the Northumberland Fusiliers

When WW1 started, James Erly volunteered for service and rejoined his old regiment, the Northumberland Fusiliers, this time serving in the 2nd Battalion embarking for France on the 15th January 1915. His battalion was attached to 84th Brigade of the 28th Division of the British Army. Private Erly was killed, at the age of 33, on the 24th May 1915. Another 47 soldiers in his battalion were also killed on that day in bitter fighting at the first Battle of Bellewaarde.1

At 2.45am on the 24th of May 1915 (Whit Monday), a ferocious German artillery bombardment slammed down on British V Corps front. The clamour of shells, machine-guns and rifle fire was accompanied by a simultaneous discharge of chlorine gas on almost the entire length of the British line. German infantry assaulted in its wake. Although the favourable wind had alerted the British trench garrison to the likelihood of a gas attack the proximity of the opposing trenches and speed of the enemy assault meant many defenders failed to don their respirators quickly enough and large numbers were overcome. But the British defence rallied and the attackers were repelled by small arms fire – except in the north, where Mouse Trap Farm was immediately overrun, and in the south where (by 10am) German infantry broke into the British line north and south of Bellewaarde Lake.

The centre of the line between these gaps held fast all day. Heroic efforts were made to retrieve the situation at Mouse Trap Farm before it was decided, that evening, to withdraw to a more defensible line. The German break-in around Bellewaarde Lake prompted the commitment of Corps reserve troops, but their arrival took time and the depleted front line battalions had to wait until the early evening before the weakened 84th Brigade was able to attack and turn the enemy out of Witte Poort Farm. 84th Brigade was ordered up from reserve to counter-attack between Bellewaarde Lake and the railway line in order to recover lost British trenches. The men had no time for food and endured a gruelling slog across the country south of Ypres (during which many men were lost to enemy shell fire). It was not until 5pm that they could launch their attack; this was successful and forced the Germans out of Witte Poort Farm and off the small ridge below which it stood. Here the Brigade dug-in to await the arrival of 80th Brigade.

Following the belated arrival of 80th Brigade a joint night counter-attack was made after 11pm; this assault, in bright moonlight, was a disaster and both 84th and 80th Brigades suffered heavy casualties. In the early hours of the morning the battle quietened. The following day saw a reduction in shelling and no attempts by the Germans to renew the offensive.

James Erly’s WW1 service record has not survived. He qualified for the 1915 Star Medal in addition to the Victory and British medals, which were awarded posthumously.

Above: The Memorial Plaque for James Erly was issued after the First World War to the next-of-kin of all British and Empire service personnel who were killed as a result of the war. The plaques (more strictly described as plaquettes) were made of bronze, and hence popularly known as the “Dead Man’s Penny”, because of the similarity in appearance to the somewhat smaller penny coin. 1,355,000 plaques were issued, which used a total of 450 tonnes of bronze and continued to be issued into the 1930s to commemorate people who died as a consequence of the war.2

James Erly is remembered at the Ypres (Menin Gate) Memorial 3, Panels 8 and 12, West-Vlaanderen, Belgium. The Ypres (Menin Gate) Memorial now bears the names of more than 54,000 officers and men whose graves are not known.

It is one of four memorials to the missing in Belgian Flanders which cover the area known as the Ypres Salient. Broadly speaking, the Salient stretched from Langemarck in the north to the northern edge in Ploegsteert Wood in the south, but it varied in area and shape throughout the war. The Salient was formed during the First Battle of Ypres in October and November 1914, when a small British Expeditionary Force succeeded in securing the town before the onset of winter, pushing the German forces back to the Passchendaele Ridge. The Second Battle of Ypres began in April 1915 when the Germans released poison gas into the Allied lines north of Ypres. This was the first time gas had been used by either side and the violence of the attack forced an Allied withdrawal and a shortening of the line of defence.

References:

1. Wartime Memories Project: 2nd Battalion, Northumberland Fusiliers