George Walter Sharpe was born in Horbury in late 1892, the second child and only son of three surviving children born to John Henry Sharpe, of Horbury, and his Ossett-born wife, Annie (nee Mercer), who married at Ossett Holy Trinity Church on the 11th June 1888. They had four children from their marriage, but one child had died before April 1911.

The family moved from Horbury to Ossett in the mid/late 1890s and in 1901 George, now aged 8 years, was living on South Parade, South Ossett with his parents and two sisters. His father, John Henry Sharpe was a wool sorter and the three children were all at school. By 1911 the family had moved to Audrey Street, Station Road, Ossett and George, by now aged 18 years was top weigher at a woollen mill. His elder sister was a rag sorter and his younger sister, aged 13, was a mother’s help.

George Sharpe’s army service record has not survived, but it is known that he enlisted at Dewsbury and joined the 1st/5th Battalion of the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry with service number 200919. He was killed in action on 9th October 1917 at the Battle of Poelcapelle. Private George Walter Sharpe was posthumously awarded the British and Victory medals, but not the 1914/15 Star, indicating that he did not serve overseas until after the 31st December 1915.

The 1/5th Battalion, Kings Own Yorkshire Light Infantry was a unit of the Territorial Force with HQ in Doncaster, serving with 3rd West Riding Brigade, West Riding Division. When war broke out in August 1914, the units of the Division had just departed for their annual summer camp, they were at once recalled to their home base and mobilised at once for war service, moving to Doncaster. In November they moved to Gainsborough and in February 1915 to York to prepare for service overseas, those men who had not volunteered for Imperial Service transferred to the newly formed 2/5th Battalion. They proceeded to France, from Folkestone landing at Boulogne on the 12th of April 1915 and the Division concentrated in the area around Estaires. On the 15th of May the formation was renamed 148th Brigade, 49th (West Riding) Division. Their first action was in the The Battle of Aubers Ridge in May 1915.

In 1916 They were in action in the Battles of the Somme. In 1917 they were involved in the Operations on the Flanders Coast and the The Battle of Poelcapelle during the Third Battle of Ypres. On the 2nd of February 1918 they transferred to 187th Brigade, 62nd (2nd West Riding) Division, absorbed the 2/5th Battalion and were renamed 5th Battalion. They were in action during The Battle of Bapaume, The First Battle of Arras, The Battle of the Tardenois, The Battle of the Scarpe, The Battle of the Drocourt-Queant Line, The Battle of Havrincourt, The Battle of the Canal du Nord, The Battle of the Selle, The capture of Solesmes and The Battle of the Sambre. At the Armistice the advanced units had crossed the Sambre and reached the Maubeuge-Avesnes road. The Division was the only Territorial formation to be selected to enter Germany and took over the area around Schleiden in December.

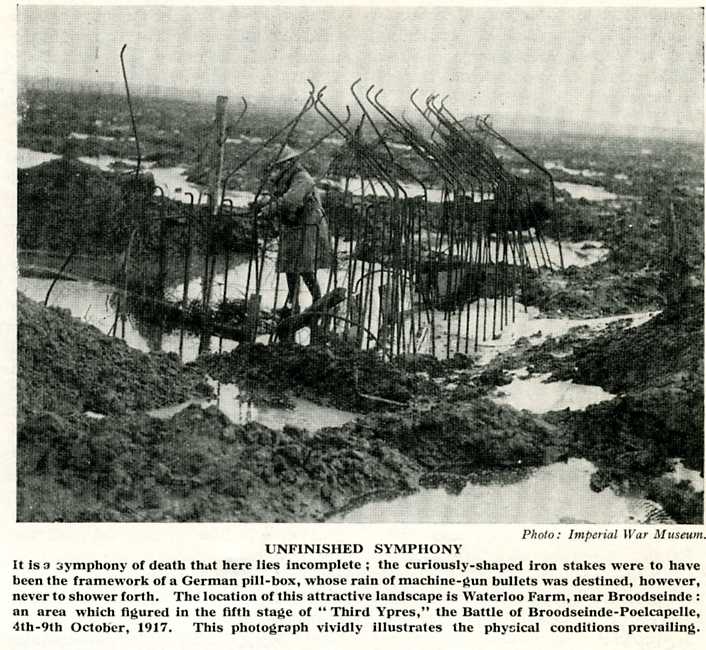

Zero hour on 9th October 1917 was 05:20 a.m., when the British Artillery barrage came down promptly on the enemy’s front line and his emplacements. But the ground was sodden, inches deep in mud and in an altogether appalling condition, so that many H.E. shells did not explode. The heavy rain of the previous day and night had turned No Man’s Land into a veritable quagmire.

The 49th Division, 148th Brigade advance that day consisted 1/4th (Hallamshire) York and Lancasters on the right hand side of the Grafenstafel road (Bellvue Spur, Ravebeek area) and the 1/5th King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry to their left (left hand side of the road) with 1/7th Battalion West Yorks further to their left and the 1/5th York and Lancasters to the rear (Fleet Cottage area.)

The 148th Brigade on the right of the 49th Division advance, stalled in the swamp astride the Ravebeek and only a few parties managed to get across the water which was now some 30 to 50 yards wide and waist deep at its midpoint. The creeping barrage was thin and moved at 100 yards in six minutes, which proved too fast for the infantry. The 1/4th KOYLI, previously in reserve were sent up to reinforce the attack. The whole Brigade was now in one line. They advanced up a long slope and came under fire from Wolf Copse on the left and Bellevue on the top of the slope. Casualties forced the troops to dig in along the slope. At 7 pm, an attempt was made to take the two pillboxes on the ridge but they were so heavily wired that the attack had to be abandoned.

The enemy were identified as the 5th Jager Regiment who were able to fire through the artillery barrage. By the afternoon of the 9th October 1917, the 148th and 146th brigades were near the red line, having suffered 2,500 casualties. 148 Brigade was relieved by the NZ Battalions at 10.30pm on the 10th October. Private George Walter Sharpe was killed in this action and his body was never recovered.

The “Ossett Observer” 1 had this short obituary for George Sharpe:

“Missing Ossett Soldier Reported Killed – Since the latter part of September, no letters or communication have been received by relatives and friends of Private George Sharpe (25), of the K.O.Y.L.I., the son of Mr. John Henry Sharpe, of Audrey-street, off Station-road, Ossett, and the mystery became more pronounced last week when a letter, which had been addressed to him, was returned with the explanation that he could not be found. This week an official notification has been received at the soldier’s home stating that Private Sharpe was killed in action on the 9th October.

The deceased enlisted about four years ago, though he did not go to the front for some considerable time. Some months ago he was on the casualty list suffering from ‘trench feet’ and a wound in the leg, but afterwards returned to the front. Before joining the army, he worked at Messrs. Poppleton’s Albert Mills, Horbury Bridge.”

Private George W. Sharpe, aged 24 years, died on the 9th October 1917, the son of John Henry and Annie Sharpe, of 7, Saville Street, Park Square, Ossett. He is remembered on Panels 108 to 111 at the Tyne Cot Memorial,1 Zonnebeke, West-Vlaanderen, Belgium. The Tyne Cot Memorial to the Missing forms the north-eastern boundary of Tyne Cot Cemetery, which is located 9 kilometres north east of Ieper town centre, on the Tynecotstraat, a road leading from the Zonnebeekseweg (N332).

The names of those from United Kingdom units are inscribed on Panels arranged by Regiment under their respective Ranks.

The Tyne Cot Memorial is one of four memorials to the missing in Belgian Flanders which cover the area known as the Ypres Salient. Broadly speaking, the Salient stretched from Langemarck in the north to the northern edge in Ploegsteert Wood in the south, but it varied in area and shape throughout the war.

The Salient was formed during the First Battle of Ypres in October and November 1914, when a small British Expeditionary Force succeeded in securing the town before the onset of winter, pushing the German forces back to the Passchendaele Ridge. The Second Battle of Ypres began in April 1915 when the Germans released poison gas into the Allied lines north of Ypres. This was the first time gas had been used by either side and the violence of the attack forced an Allied withdrawal and a shortening of the line of defence.

There was little more significant activity on this front until 1917, when in the Third Battle of Ypres an offensive was mounted by Commonwealth forces to divert German attention from a weakened French front further south. The initial attempt in June to dislodge the Germans from the Messines Ridge was a complete success, but the main assault north-eastward, which began at the end of July, quickly became a dogged struggle against determined opposition and the rapidly deteriorating weather. The campaign finally came to a close in November with the capture of Passchendaele.

The German offensive of March 1918 met with some initial success, but was eventually checked and repulsed in a combined effort by the Allies in September.

The battles of the Ypres Salient claimed many lives on both sides and it quickly became clear that the commemoration of members of the Commonwealth forces with no known grave would have to be divided between several different sites.

The site of the Menin Gate was chosen because of the hundreds of thousands of men who passed through it on their way to the battlefields. It commemorates those of all Commonwealth nations, except New Zealand, who died in the Salient, in the case of United Kingdom casualties before 16 August 1917 (with some exceptions). Those United Kingdom and New Zealand servicemen who died after that date are named on the memorial at Tyne Cot, a site which marks the furthest point reached by Commonwealth forces in Belgium until nearly the end of the war. Other New Zealand casualties are commemorated on memorials at Buttes New British Cemetery and Messines Ridge British Cemetery.

The Tyne Cot Memorial now bears the names of almost 35,000 officers and men whose graves are not known. The memorial, designed by Sir Herbert Baker with sculpture by Joseph Armitage and F.V. Blundstone, was unveiled by Sir Gilbert Dyett on 20 June 1927.

The memorial forms the north-eastern boundary of Tyne Cot Cemetery, which was established around a captured German blockhouse or pill-box used as an advanced dressing station. The original battlefield cemetery of 343 graves was greatly enlarged after the Armistice when remains were brought in from the battlefields of Passchendaele and Langemarck, and from a few small burial grounds. It is now the largest Commonwealth war cemetery in the world in terms of burials. At the suggestion of King George V, who visited the cemetery in 1922, the Cross of Sacrifice was placed on the original large pill-box. There are three other pill-boxes in the cemetery.

There are now 11,956 Commonwealth servicemen of the First World War buried or commemorated in Tyne Cot Cemetery, 8,369 of these are unidentified.

References:

1. “Ossett Observer”, 17th November 1917