Ernest Lythell was born in Horbury in 1896, the eldest child, and only son of three surviving children born to George William Lythell and his wife Mary (nee Harrop), who married at St Peter and St Leonard’s Church, Horbury on the 21st July 1894. Ernest was baptised at the same Church on the 13th March 1896. The Lythells had five children from their marriage, but two had died before 1901.

George William Lythell, a football stitcher at the time of Ernest’s birth in 1896, but a coach trimmer in 1901, when he was living in Birmingham with his wife and three children, Ernest and two girls. The girls, then aged four and one year, were born in Ossett and Featherstone, suggesting that the family had only recently moved to Birmingham.

Shortly afterwards, George William Lythell, died in Camberwell, London, leaving his widow, Mary with three children under the age of six years. By 1907 Mary Lythell had returned to Yorkshire, and in 1907 she married John Stewart in the Dewsbury Registration area and by 1911 she was living and working as a housekeeper to Albert Carr at Roundwood, Ossett. Mary now had five children, three from her first marriage, and two, both born in Ossett, from her marriage to John Stewart, who at that time was living elsewhere. Ernest Lythell was now aged 15 years and working as a pony driver at Old Roundwood colliery.

At Wakefield Holy Trinity Church on the 28th June 1914, Ernest Lythell, aged 18 and a miner, married 18 year old spinster Phyllis Fricker. Both gave their address as 33, Rodney Yard, Wakefield and in September 1914 a daughter named Bertha Lythell was born in the Hemsworth area.

Ernest Lythell’s army service record has not survived, but it is known that Ernest enlisted at Doncaster, probably because Ernest had relatives in South Yorkshire. He embarked for France on the 11th September 1915 with the 10th Battalion, KOYLI and service no. 3/2916 and two weeks later he was dead. Number prefixes were used by some regiments to identify the particular battalion that a man served with. The 3/ and 4/ prefixes are common for Special Reserve and Extra Reserve recruits, and during World War One, many service battalions (the so-called “Pals’ Battalions” in particular) followed suit.

Private Ernest Lythell was posthumously awarded the the British and Victory medals and also the 1914/15 Star medal in recognition of his service overseas before the 31st December 1915. Ernest Lythell’s widow, Phyllis, remarried in Wakefield in June 1923 when she took Humphrey T. Jones as her second husband.

The 10th (Service) Battalion, KOYLI was formed at Pontefract in September 1914 as part of K3 and came under command of 64th Brigade in 21st Division. The Battalion moved to Berkhamsted and then to Halton Park (Tring) in October 1914, going on to billets in Maidenhead in November. They returned to Halton Park in April 1915 and went on to Witley in August. In September 1915, they landed in France. On the 13th February 1918 the battalion was disbanded in France, with at least some of the men going to 20th Entrenching Battalion. Ernest Lythell died during the Battle of Loos, during which the 21st Division of the ‘New Army’, which included the 10th Battalion of KOYLI faced the Germans in battle for the first time.

“Battle of Loos – The Attack Begins: Around 5:50 AM on September 25, the chlorine gas was released and forty minutes later the British infantry began advancing. Leaving their trenches, the British found that the gas had not been effective and large clouds lingered between the lines. Due to the poor quality of British gas masks and breathing difficulties, the attackers suffered 2,632 gas casualties (7 deaths) as they moved forward. Despite this early failure, the British were able to achieve success in the south and quickly captured the village of Loos before pressing on towards Lens.

In other areas, the advance was slower as the weak preliminary bombardment had failed to clear the German barbed wire or seriously damage the defenders. As a result, losses mounted as German artillery and machine guns cut down the attackers. To the north of Loos, elements of the 7th and 9th Scottish succeeded in breaching the formidable Hohenzollern Redoubt. With his troops making progress, Haig requested that the 21st and 24th Divisions be released for immediate use. French granted this request and the two divisions began moving from their positions six miles behind the lines.

Battle of Loos – The Corpse Field of Loos: Travel delays prevented the 21st and 24th from reaching the battlefield until that evening. Additional movement issues meant that they were not in position to assault the second line of German defenses until the afternoon of the September 26. In the meantime, the Germans raced reinforcements to the area, strengthening their defenses and mounting counterattacks against the British. Forming into ten assault columns, the 21st and 24th Divisions surprised the Germans when they began advancing without artillery cover on the afternoon of the 26th. Largely unaffected by the earlier fighting and bombardments, the German second line opened with a murderous mix of machine gun and rifle fire. Cut down in droves, the two new divisions lost over 50% of their strength in a matter of minutes. Aghast at the enemy losses, the Germans ceased fire and allowed the British survivors to retreat unmolested. Over the next several days, fighting continued with a focus on the area around the Hohenzollern Redoubt.” 1

The “Ossett Observer” 2 had this short obituary for Ernest Lythell:

“Ossett Soldier Reported Killed – Missing Since the Battle of Loos – Nothing has since been heard of Grenadier Ernest Lythell, a young Ossett soldier, of the 10th Battalion, King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry, who was reported missing after the severe engagement at Loos in September last and this week his mother, who resides at Shepherd-hill, Flushdyke, has received an official intimation of his death.

The deceased, who was only 20 years old, joined the army three weeks after the outbreak of the war. Previously he worked at Old Roundwood colliery and afterwards at South Kirkby.”

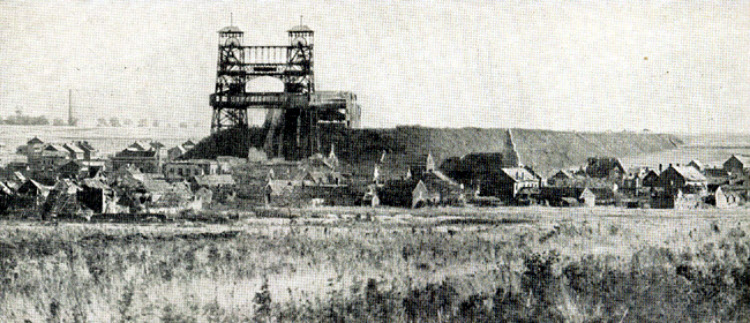

Above: The mining town of Loos (pronounced “Loss”), dominated then by the ironwork of a pit winding gear known to the British as “Tower Bridge”. Behind it, the heights of the long Loos Crassier (slag heap) and the railway running up to the pit head. Loos today bears scant resemblance to this.3

Private Ernest Lythell, aged 20 years, died on the 27th September 1915. He is remembered on Panels 97 and 98 at the Loos Memorial, 4 Pas de Calais, France. The Loos Memorial forms the sides and back of Dud Corner Cemetery. Loos-en-Gohelle is a village 5 kilometres north-west of Lens, and Dud Corner Cemetery is located about 1 kilometre west of the village, to the north-east of the N943, the main Lens to Bethune road.

Dud Corner Cemetery stands almost on the site of a German strong point, the Lens Road Redoubt, captured by the 15th (Scottish) Division on the first day of the battle. The name “Dud Corner” is believed to be due to the large number of unexploded enemy shells found in the neighbourhood after the Armistice.

The Loos Memorial commemorates over 20,000 officers and men who have no known grave, who fell in the area from the River Lys to the old southern boundary of the First Army, east and west of Grenay. On either side of the cemetery is a wall 15 feet high, to which are fixed tablets on which are carved the names of those commemorated. At the back are four small circular courts, open to the sky, in which the lines of tablets are continued, and between these courts are three semicircular walls or apses, two of which carry tablets, while on the centre apse is erected the Cross of Sacrifice.

Courtesy of Mark Smith

References:

1. World War I: Battle of Loos

2. “Ossett Observer”, 26th February 1916