Edgar Daniel was born in Ossett on the 24th March 1890, the eldest of four children of Wakefield born George Henry Daniel and Mary Ellen Edgar of Sheffield, who married in her parish in early 1889. Edgar was baptised at on the 25th May 1890 at Wicker, a chapelry in Sheffield parish.

By 1891 George, aged 22 years, a wheelwright had moved from his Alverthorpe family home and was living with his wife, 21 year old, Mary Ellen and 1 year-old Edgar on Dale Street, Ossett. By 1894 it appears that the family had moved on to Wakefield and thence, by 1898, to Warrington in Lancashire.

Sadly, Edgar’s mother, Mary Ellen died in summer 1900, aged 31 leaving George, a widower with four children all under the age of 12 years. In 1901 he was living in Warrington with his four children. The family had a house servant.

George married Charlotte Barbara Stormont in the Runcorn area in late 1909 and in 1911, the couple were living with two of George’s children in Warrington, where George was still working a wheelwright. Edgar Daniel was no longer in the household having enlisted in the Royal Navy on the 27th March 1908; just three days after his 18th birthday.

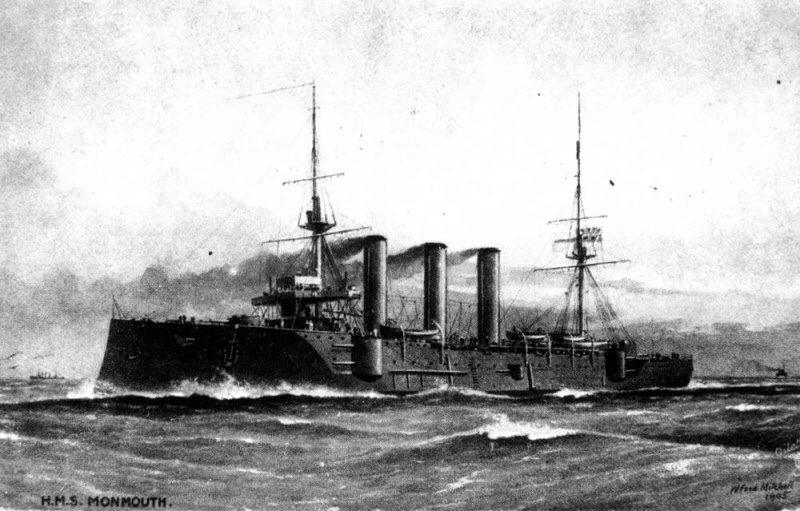

In 1911, aged 21 years, he was serving as a private with the Royal Marines, Royal Navy on the China Squadron, 1st class cruiser H.M.S. “Monmouth”, off Columbo, Sri Lanka. He was one of 87 Royal Marines aboard with 31 officers and 515 seamen.

On the 1st November 1914, the British Royal Navy confronted a German squadron outside the port of Coronel, close to Chile’s second city of Concepcion. The Germans won a resounding victory, sinking two of the four British ships with the loss of over 1,600 lives. Not a single German sailor died. Not only was it Britain’s first naval defeat of WW1 but it was its first anywhere in the world in over a century, dating back to the war of 1812 against the United States. Britannia had ruled the waves for generations, and the defeat at Coronel sent shock waves through its empire and beyond.

The Panama Canal had only just opened and until then, ships crossing from the Atlantic to the Pacific had to round the bottom of South America and travel up the Chilean coast. The Germans were trying to disrupt British trade to hamper their WW1 war effort. The German squadron that fought at Coronel was under the command of Maximilian von Spee, an experienced admiral. The German vessels were using modern warships including the the armoured cruisers “Scharnhorst” and “Gneisenau”. Their crews were very experienced having been together for years. In contrast, the British warships, led by Rear-Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock, was outdated. The British ships were old and the two armoured cruisers H.M.S. “Good Hope” and H.M.S. “Monmouth” were poorly designed. All the odds were stacked against them.

The battle started in the late afternoon and went on into the night. It was clearly visible from the shoreline of Chile, which remained neutral throughout World War One. Spee’s flagship, Scharnhorst, engaged Good Hope while Gneisenau fired at Monmouth. The German shooting was very accurate, with both armoured cruisers quickly scoring hits on their British counterparts while still outside six-inch gun range, starting fires on both ships.

Cradock, knowing his only chance was to close the range, continued to do so despite the battering that Spee’s ships inflicted. By 19:23 the range was almost half of that when the battle began and the British ships bore onwards. One shell from Gneisenau blew the roof off Monmouth’s forward turret and started a fire, causing an ammunition explosion that completely blew the turret off the ship. Spee tried to open the range, fearing a torpedo attack, but the British were only 5,500 yards (5,000 m) away at 19:35. Severely damaged, Monmouth began to slow and veered out of line.

H.M.S. “Good Hope” was the first British ship to sink, taking Rear-Admiral Cradock with it. Just over an hour later, the Germans sank H.M.S. “Monmouth” with the loss of all hands.

After their victory, the Germans sailed northwards and docked at the Chilean port of Valparaiso, where they were feted as heroes by the large local German community. But von Spee, it seems, was in no mood to celebrate. He had used much of his ammunition at Coronel and was far from home, with few options to refuel. He was expecting a British backlash. When given a bouquet of flowers in Chile he reportedly said: “These will do nicely for my grave.” Just over a month later he was dead, one of the hundreds of German victims at the Battle of the Falkland Islands.

Above: H.M.S. Monmouth was sunk in the Battle of Coronel, off the coast of Chile, on the 1st November 1914. There were no survivors and 738 members of the crew lost their lives.

On 1st November 1914 Edgar Daniel, age 24 years was killed or died as a direct result of enemy action. His body was not recovered for burial and he was presumed drowned. Edgar is remembered on panel 4 of the Plymouth Naval Memorial.1

More than 45,000 men and women lost their lives while serving with the Royal Navy during the First World War. After the Armistice, the naval authorities and the Commonwealth War Graves Commission were determined to find an appropriate way to commemorate naval personnel who had no grave. With its central position on the Hoe overlooking Plymouth Sound in Devon, the Plymouth Naval Memorial is a well-known local landmark. The memorial commemorates more than 7,200 naval personnel of the First World War and nearly 16,000 of the Second World War who were lost or buried at sea.

Edgar Daniel was posthumously awarded the British and the Victory medals in recognition of his service in a theatre of war. He was also awarded the 1914-15 Star medal for his service on or before 31st December 1915. Until now Edgar Daniel has not been remembered on any Ossett War Memorial or Roll of Honour.

References: