Charles Henry Derry was born on the 4th July 1886, the son of Lichfield-born Charles and his wife Eliza, who was born in Featherstone. Charles Henry was baptised at Ossett Holy Trinity Church on the 26th January 1887 when his parents, Charles, a miner, and Eliza were living on Dale Street, Ossett.

In 1891 the couple were still living in Dale Street, now with their six children: five girls and one boy. Charles Henry, was the youngest of the children, all born between 1870 and 1886. In 1901, the family remained living on Dale Street, but two of the girls have married and moved away. Charles, now aged 14, is working as a miner.

On the 5th November 1910, Charles Henry Derry, aged 24, married 20 year-old Horbury girl, Elsie Hey, at Horbury St Peter’s Church. Banns were also read in South Ossett. In 1911, Charles Henry and Elsie were living with their one month-old son, Charles, at 8 Teal’s Yard, Dale Street, Ossett and Charles Henry was working as a miner. Sadly, their baby Charles died in the same quarter as he was born, under the age of three months. In June 1914, the couple had a baby girl, Jessie Derry.

Charles Henry Derry’s army service record has survived. Aged 29 years and 2 months, Charles Henry Derry of 8, Teal Street, Ossett Common enlisted at Leeds on the 14th August 1915. He was 5’ 0½” tall and weighed 120 lbs, with a chest measurement of 31″. His physical development was recorded as ‘fair’. Charles Derry was posted to the West Yorkshire Regiment, 88th Training Reserve Battalion on the 17th August 1915 and embarked for France on the 9th March 1916. He was appointed paid Lance Corporal on th e1st August 1916.

On the 29th April 1917, Charles Henry’s service record indicates “To England for Munitions for release under W.O. letter” and he returned to England on the 10th May 1917 when 17/1708 Lance Corporal C. H. Derry had served 1 year and 270 days in the West Yorkshire Regiment. He was transferred to Class W army reserve and a note was attached indicated that he had pains in the head, dizziness and concussion from the shells, which was the reason for his transfer to ‘W’ reserve for employment as a miner with Messrs. Terry Greaves Co Ltd., Old Roundwood Collieries, Wakefield. These were symptoms typical of shell shock and his obituary confirms that this was the case. Class ‘W’ Reserve was ‘for all those soldiers whose services are deemed to be more valuable to the country in civil rather than military employment’.

Men in these classes were to receive no emoluments from army funds and were not to wear uniform. They were liable at any time to be recalled to the colours. From the time a man was transferred to Class ‘W’, until being recalled to the Colours, he was not subject to military discipline.

The call for men at the front was so great that Charles Henry Derry was subsequently recalled to serve in France and on the 13th December 1917, he was posted to 1/6 Durham Light Infantry (service number 79543), at Margate. He may have spent some time at home in early 1918, but he subsequently embarked from Folkestone on the 20th April 1918, arriving at Etaples on the 21st April.

He was reposted to 1/6 Durham Light Infantry on the 23rd April 1918. Charles Henry Derry was reported missing between the 27th to the 30th May 1918 and he died from a shot wound to the abdomen at St Erme on the 31st May 1918. His transfer home whilst in the West Yorkshire Regiment and his subsequent recall to the front in the 1/6 Durhams was too much for the army bureaucracy and in September 1918 the army wrote to his widow to ask when Charles Henry “came home.” The confusion continued into the 1920s, and his widow was required to write to remind the army that his medals had not been issued. This led to a flurry of correspondence between the West Yorkshire and Durham Light Infantry Regiments before the British and Victory medals were finally issued to his widow.

His Medal Card is recorded under his West Yorkshire Regiment Service no. 17/1708 and has the British and Victory medals crossed out. They were subsequently issued, but by his second and final Regiment, the Durham Light Infantry. The Medal Card also records his period in both Regiments as a Private, but he was a paid Lance-Corporal in the West Yorkshire Regiment from the 1st August 1916 to the 10th May 1917.

On the 17th October 1919, his widow, Elsie Derry, of 44, Spring End, Horbury returned the Army pro-forma requesting details of the kin of the deceased soldier. He had one child, Jessie, born on the 17th of June 1914, but there was no reference to Arthur who was recorded as their son, aged 1 month, in the 1911 census.

Charles Henry’s father had also died by this time. His mother, Eliza Derry lived at 29, Woodbine Street, Ossett and his sisters were named as Susie Derry (56) of the same address, Mrs. Kemp (50) of Roundwood Ossett , Mrs. Lythell (47) of Shepherd’s Hill, Ossett (45), Mrs. Winpenny of Mitchell’s Row, Ossett and Mrs. Brown of South Emsall. His widow and child were awarded a pension of 20/5d per week from the 27th January 1919.

The “Ossett Observer” 1 had this short note about Private Derry being missing in action:

“Private C.H. Derry (33), Durham Light Infantry, a married man, whose wife, child and widowed mother reside at Woodbine-street, Ossett, is posted as missing from his regiment, somewhere in France. Formerly employed at the Old Roundwood Collieries, he had served three years in the army. In May last year he received his discharge, suffering from shell shock, but in the following August he had to rejoin his regiment.”

This was followed up six months later by this short obituary:

“Horbury Man’s Fate: Died From Wounds – Following enquiries news has been received from the War Office that Private C.H. Derry (31), Durham Light Infantry, Spring-end, Horbury, died in May last at a field hospital at St. Erme from gunshot wounds in the abdomen and was buried in the military cemetery there. Deceased, who used to work at Old Roundwood Collieries, leaves a widow and a child.”

The 1/6th Battalion of the Durham Light Infantry was formed in August 1914 at Bishop Auckland and was part of DLI Brigade, Northumbrian Division. They moved to Bolden Colliery in early August, then to Ravensworth Park and were at Newcastle by October. On the 17th April 1915, the battalion landed at Boulogne, and on the 14th May 1915 they joined 151st Brigade in the 50th (Northumbrian) Division.

On the 3rd June 1915, after taking heavy casualties, 1/6th and 1/8th Battalions merged to form 6/8th Battalion, but they resumed their original identities on the 11th August 1915. On the 15th July 1918, again following heavy casualties, the battalion was reduced to cadre strength and transferred to Lines of Communication. On the 16th August 1918, they transferred to 117th Brigade in 39th Division and on the 6th November 1918, the battalion disbanded in France.

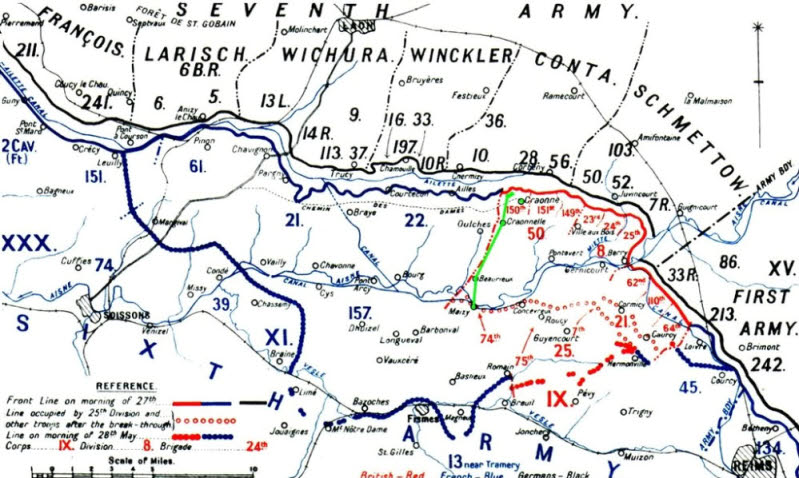

The 5th, 6th, and 8th Battalions of the Durham Light Infantry as part of the 151st Brigade of the 50th Division were east of Craonne, which is about 3-4 miles WSW of Amifontaine when they were heavily attacked on the opening day of the German Blucher Offensive, starting on the 27th May 1918. 50th Division had the misfortune to be involved in three German Offensives in the Spring of 1918. It was part of Fifth Army during the Michael offensive on the Somme (March 1918); it had been moved to the Lys and was caught in the Georgette offensive (April 1918) and was sent to the Chemin des Dames as part of IX Corps to rest and ’embed’ the new recruits (having lost so many men). Unlike the earlier battles, 50th Division was now in the front line and not held in reserve.

“At 0100 on 27 May, over 3,700 German guns opened up in the fire pattern devised by Colonel Bruchmuller, saturating the gun emplacements, isolating the HQs as the communication lines were broken, and disorientating the defenders. The effect of gas shells was not to kill, but to cause every possible form of nuisance to the key personnel of the British Army in carrying out their duties. Everything was made more difficult, everything was more uncomfortable, everything was more tiring and stressful. The barrage went through its phases until the stormtroopers burst out of their trenches at 0340. No one in either 8th Division or 50th Division Headquarters had any idea of what was happening.

Officers like Captain Lyon (1/6 Durhams, 151 Brigade, 50th Division) had to emerge from their dugouts to check for themselves. When he looked at the German lines he could see that the new German tactics were to put the advance troops immediately behind the barrage so that the British defence had no time to recover. He observed files of German troops immediately in front of his own line. They were advancing leisurely meeting with little or no resistance. When he looked up he could see German aircraft sweeping the trench line with machine gun fire. It soon became apparent that the British defence had crumpled.

Caption Lyon (1/6 Durham Light Infantry) had been to told to make a stand with the 1/5 Durhams on a wooden hill, the Butte de l’Edmonde. As they advanced on the hill they became aware it was already in German hands. As he lead his men in retreat under machine gun fire from both the hill and from aircraft, Lyon lost men until his group was reduced to a handful of wounded men. Eventually he instructed them to surrender as they were clearly surrounded by Germans with levelled rifles.

The German army had had a startlingly successful first day – it had ripped a hole in the Allied lines 35 miles wide and 12 miles deep. By the 30 May the Germans had advanced 40 miles and reached the Marne. It would appear that Ludendorff fell for his own trap and started to move his reserves to reinforce the Aisne Offensive. Foch decided the German’s Aisne offensive made no strategic sense so he decided to wait before he moved reinforcements. When French resistance stiffened and the battle spluttered to a conclusion in June, the Germans were left holding a rather large salient. Then Ludendorff attempted to widen the salient with Operation Gneisenau. The French Third Army, holding the ground he intended to take, was fully aware of what was coming. Their tactics were not to hold the front line in depth, to allow the Germans to advance into artillery fire and eventually to counter attack behind a creeping barrage supported by tanks and low flying aircraft. In the end Ludendorff was forced to call off the offensive.” 2

Private C.H. Derry, aged 33 years, died on the 31st May 1918 from wounds sustained during the Third Battle of the Aisne, which began on the 27th May 1918.

Above: Map of the Third Battle of the Aisne on 27th May 1918, showing the position the 50th (Northumbrian) Division and 151 Brigade (in red) where the 1st/6th Battalion, Durham Light Infantry of Private Charles H. Derry was virtually wiped out, east of Craonne, by the German advance.

Private Charles Henry Derry is buried at grave reference B12 at the St. Erme Communal Cemetery Extension 3, Aisne, France. The military cemetery is an extension of the local communal cemetery of the village of St Erme, which is situated 15 kilometres south-east of Laon and 30 kilometres north-north-west of the town of Reims.

A German Extension was made on its West side, but was removed after the Armistice. The Commonwealth Extension was made between the Armistice and the removal of the German Extension. In 1938, 12 soldiers were moved to this Cemetery from isolated graves.

There are 76 Commonwealth burials of the 1914-18 war, 7 of which are unidentified and 8 of the 1939-1945 war, commemorated in this site. 36 from the 1914-18 War were originally buried in Ramecourt Communal Cemetery. Many of the graves, identified collectively but not individually, are marked by headstones bearing the superscription “Buried near this spot.”

References:

1. “Ossett Observer”, 15th June 1918

2. “Not Again” – The German Offensive on the Aisne: 27th May 1918 by Peter J. Palmer, The Western Front Association