The origins of our town of Ossett have frequently been challenged by researchers searching for its earliest beginnings. Some things, as you will see can be interpreted whilst others are indisputable and require no interpretation. So when the Domesday Book of 1086 records that Ossett, or as it was then known, Osleset , existed almost a 1000 years ago it’s best to believe it; not least because it’s true even though it’s likely that at this time only seven men lived here with their families comprising maybe 25-35 persons in total. A tiny village one might think about these 35 souls until the context tells us that they were probably the only survivors of Ossett as William The Conqueror, by then King William, ensured the death and destruction of virtually everyone and everything to the east of what was left of our village.

The question is whether Ossett has even earlier credentials as to its origins. There has been much debate over the years as to roman activity hereabouts, quoting for example, Ossett Street Side as possibly part of the Roman Road known to have run from Manchester through Dewsbury to Wakefield, Doncaster and beyond. Roman coins have been found at Alverthorpe, at Roundwood and in 1870 at Streetside itself. In 1930 a roman mosaic pavement was unearthed during the Lupset development. It’s reasonable to interpret this as roman presence even if it may only be transient.

More recently, in 2007, at Mitchell Laithes Rye Royds (field name), an archaeological appraisal was undertaken which recorded short episodes of occupation dating back to 3500-2000 BC .For the avoidance of doubt that is more than 5000 years ago. The finds included ware pottery and an early bronze age round barrow (burial pit) containing cremated remains of four persons, of varying ages, two with degenerative disease. At least two of the persons were of status, who died at a similar time and may have been man and wife. Some of the cremated remains were in a collared urn, dating 1920-1680BC. Iron age activity was represented by pits containing pottery and elsewhere were other Roman finds, some dating to the 4th/5th century. Signs of extensive iron-smithing in the roman period were also found as was later medieval and early post-medieval activity.Whilst these occupations were said to be short term the findings indicate habitation over extensive periods of time varying from 3000BC – 1700AD.

Leaving aside the archaeological findings in 2007 historians tend to agree that it took 100 years or so for the north to recover from William The Conqueror’s slash and burn tactics in the 11th Century. Nonetheless they were still controlled by the Norman feudal system which tied the ordinary hard working classes to the Lord of the Manor to whom they were largely beholden.

By the 13th century Ossett was a farming community but with the necessary carpenter, mason, cobbler, tailor, smithy, cordwainer, shoemaker etc engaged to ensure the water wheels and windmills could turn, that hides were tanned, that metal was worked , cloth was made and coal was dug. Incidentally at that time, some 700 years ago Roundwood was the place to go for coal.

Above. Poll Tax Riots 1381

The 14th century saw the beginning of the end of the feudal system as independent farmers, known as yeomen, began to thrive. The progressive Poll Tax was introduced in 1379 when all men above the age of 15 paid the tax according to their status. In Ossett 73 men and women, whose names echo down the centuries, paid between 4d. and 12d. each. To make things worse an outbreak of the Black Death hit the country, including this corner of Yorkshire. In these days dwellings were largely built of wood, without windows but with mud plaster, a thatched roof and earth floors. Nagging wives were ducked and witches burned. Working hours were long.

By the 16th century the number of independently owned farms had increased but there was still no evidence of large scale industrial activity and the local economy continued to rely on agriculture, coal and cottage industries like cloth making. In 1593 the plague broke out in Ossett when the Denton family lost seven men, women and children and two others who were all buried at their Sowood Farm home on Denton Lane.

In the 17th Century on 21st May 1642 Ossett found itself involved in the English Civil War when the Parliamentary army (Roundheads) passed through Ossett township on their way to attack Thornhill Hall which was in the hands of the Savile family who were staunch Royalists(Cavaliers). Cannon placed at the bottom of Runtlings Lane fired at will at the Hall until the family was “invited to leave”. The Hall was subsequently burned and destroyed to its foundations. Apocryphal or not it is also said that Cromwell once spent a night at Low Laithes Farm.

It was an age when attendance at church was compulsory and it was a serious offence to not attend church…..unless that is you were a Roman Catholic or a Quaker. In October 1683 eleven Ossett people, nine Quakers and two Popish recusants, were prosecuted for being dissenters. This at a time when there was still a belief in fairies, the Devil, witches and evil spirits. The woollen cloth industry had fallen on hard times and, to help, the Government ruled that no person be buried in imported material or any fabric other than woollen cloth.

“A bit of old Ossett 17th Century”. Courtesy WMDC Libraries.

By the early 18th century there were houses on Dale Street, Town End, West Wells, Queen Street, Manor Road and Gawthorpe. Ossett had to wait another 100 years before it enclosed common land to encourage more modern techniques of farming and so in the 18th century much of this land was used only for grazing. Ossett Lights had been largely coppiced by this time but there was still dense woodland at Roundwood and Southwood (Sowood).

What roads existed were seas of mud and rutted when dry, not metalled and difficult for packhorse and for carts especially in winter. Conditions were crude, disease was rife and there was of course no water supply, no sewerage systems or sanitation. Towards the end of the Century the development of steam and rotary engines and other technological time and effort inventions helped mill owners to improvise to survive. These practices though took their toll on the handloom workers whose wages fell three fold as the mills grew in number and size. Flour prices rocketed putting bred from wheat flour beyond the reach of most people.

The canal in Healey came into use about 1770 and for many years hence it carried coal, rags and shoddy and other traffic to and from the Healey mills within and between Yorkshire and Lancashire. A lot was happening but there remained much more to do to improve the quality of life. In the absence of leadership and authority it was difficult to see how it could be done.

In the 19th Century the first national census was held in 1801 and recorded that Ossett’s population was 3424 persons. Twenty years later the 1821 Census records the Ossett population as 4764. Ossett celebrated the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1814 by the establishment of a Church of England Sunday School on Old Church Street a short distance from the Anglican Church, rebuilt in 1806 in the Market Place

The original Wesleyan Church on Wesley Street (formerly Oxley Lane) had led by example by using their old church as an elementary school when their New Wesleyan Church was built next door in 1867. An improvement for the Church was the provision of a burial ground where 360 people were interred between 1825 and 1879. Many of the bodies are believed to lie beneath parts of Wesley Street and Ventnor Way (formerly Back Lane).

The making and improvements of roads, the canals, the enclosure of land in the early 19th Century and the increasing size of mills and their use of steam and other technology were indicative of the country’s and Ossett’s industrial activities. In 19th century Ossett about twenty mills were built to handle stages of yarn , cloth manufacture and shoddy as Ossett became more involved in rags processing. This latter practice was simple, cheap and skill requirements were such that some rag merchants would employ workers in their own homes . The mills provided essential work for the masses but they left their mark nonetheless and every mill chimney discharged black smoke from out of date and inadequate boilers. There was nobody to address it.

The first railways near Ossett were built in the 1840’s but none reached the town itself until the 1860’s when Flushdyke and Ossett (old) station opened. By the 1880’s the town had three railway stations , at Flushdyke Station Road (new built 1889) and Chickenley Heath.

The above improvements were also a boost for the 18th and 19th century local mining industry which had grown in importance helped by the improved roads, canals and steam. Even so it was 1866 before the Wakefield to Halifax Turnpike road removed its toll bars at Ossett and Dewsbury. The Low Laithes and Roundwood collieries were the principal Ossett mines together with the Shaw Cross Colliery just over the Dewsbury boundary.

Throughout the ages Ossett’s principal sources of employment were cloth, coal and farming. What hadn’t developed though was the structure of local government which remained in a primitive state for lack of leadership. Whilst Ossett got its police station in 1867 the Board of Surveyors , established in 1835, was supposed to be responsible for roads, lights and drainage. However it did little to improve them on behalf of a growing population which desperately needed improvements to its drainage, sanitation, water and gas supply and rubbish removal. It was 1871 before there were signs of improvements from the Board of Health, the Local Board. Ossett was still drawing water from its wells but in 1876 a water pipeline was built from Dewsbury to Ossett, a sewerage system began in 1877 but drainage of some parts of the town didn’t get underway until the 1890’s.

It wasn’t for the lack of money, faith or fervour for religious belief and dedication which continued apace in 19th century Ossett with the building of ten new churches and chapels in the ten years between 1857 and 1867.

There were visible signs in these years that the landscape of Ossett was changing; the Local Board was superceded in August 1890 by the town’s incorporation as a Borough. Station Road had its railway station which had roughly one hundred trains pass through it each day and in the 1880’s and 1890’s town centre was graced by distinguished and sophisticated new buildings. In 1894 Ossett’s Magistrates Court sat for the first time, in the Mechanics Institute.

Ossett grew up in these years as it dragged itself into the second half of the 19th century and its population had grown fourfold between 1801 and 1901. For perhaps the very first time there was a sense of pride in the town and many, but not all of the people were in a much better place than hitherto. Yet there was still more work to do as Ossett looked forward to its future in the 20th Century.

With the exception of the Grammar School, which moved in 1906 to its new home on Storrs Hill, it was 1904 before education became a responsibility of the Corporation. Most elementary schools until then were church schools . The first school to be built in Ossett with public funds was Southdale Council School which opened on August 22nd 1908. This was the very same year which saw the opening of the home of the Corporation, The Town Hall.

This ramble which began in earnest almost 1000 years ago is left here at the end of the 19th century. Ahead of Ossett in the 20th and 21st centuries were two wars with huge pain and a dreadful loss of life, two pandemics and a deep economic depression in the 1920’s. Some of these stories are told elsewhere on Ossett Heritage and others need to be told in another place at another time.

Alan Howe October 2021.

With thanks to those who went ahead of me. John Goodchild, Norman Ellis, John Pollard, Colin Oldroyd, Richard Glover and David Scriven who all knew much more than I ever did.

Above: The Ossett War Memorial

On the 11th of November 2018, exactly 100 years after the Armistice was signed to signal the end of World War One, the names of the 400 Ossett men and women who gave their lives in WW1 and WW2 were unveiled on granite setts laid around the base of the Ossett War Memorial in the Market Place, Ossett.

The names of the Ossett Fallen from the two World Wars have never been available publicly and the Ossett War Memorial has never included the names of these brave men and women. Thanks to a grant from Wakefield Metropolitan District Council and the work of a small project team led by Alan Howe, the names are now available to be remembered by Ossett people when the engraved granite setts were unveiled on the 11th of the 11th 2018.

The Ossett War Memorial was given a face lift as a part of the War Memorial project and some of the damaged lettering was reinstated.

A Facebook Group “The Ossett Fallen” has been set up. This Group is for those who wish to keep up to date with the War Memorial Project to honour the 404 Ossett men and women who lost their lives during WW1 and WW2.

It is also the place where you can post your comments and questions about the War Memorial, the Ossett Fallen AND other Ossett men and women who served in WWI & WWII but survived. In this way the Group will itself become a piece of history. Your views will have been recorded for posterity. Those who follow us will be able to look back and see the importance this generation attached to the memories of these men and women of Ossett who fought for our freedom.

Ossett Heritage is no longer complementary to Ossett Through The Ages (OTTA) which used to have a significant number of posts relating to the Ossett War Memorial Project and The Ossett Fallen in WWI & WWII.

Above: Ossett Town Centre and the War Memorial in April 2019, picture courtesy of Laura Hartley.

From Mayall’s Annals of Yorkshire 1734 – 1736

“The inhabitants of Ossett, a village three miles from Wakefield, have been employed in making broad woollen cloth from time out of mind. In this year the weavers, etc., employed in that trade, had to work 15 hours every day for eight pence. A horn was blown at five o’clock in the morning, the time for beginning, and at eight at night, the time for leaving their work. The clothiers had to take their goods to Leeds to sell, and had to stand in Briggate in all sorts of weather.

About the year 1736, Richard Wilson, a resident of Ossett, made two pieces of broadcloth; he carried one of them on his head to Leeds and sold it. The merchant being in want of the fellow piece, he went from Leeds to Ossett, then carried the other piece to Leeds, and then walked to Ossett again; he walked about forty miles that day.”

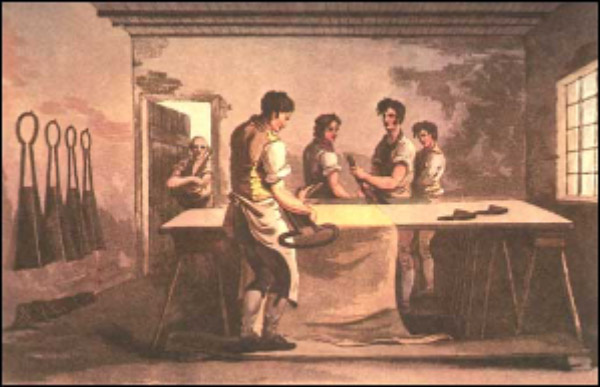

The town of Ossett occupies a hill top site off the line of major roads, although the Wakefield and Halifax Turnpike (1741-1870) passed about half a mile to the north of the town centre. By the early 1700’s handloom weavers were working fifteen hours a day at home, the early ‘cottage industry’, to produce broadcloth. Many homes in Ossett had one or more looms and whole families were involved in the various operations of making cloth.

These small enterprises carried their pieces to Leeds, either on their heads or backs, or on the backs of donkeys. In the Cloth Hall at Leeds the pieces were displayed on stalls for the inspection of the merchants. These forerunners of the woollen industry traded in a very small way, and to receive an order for half a dozen or a dozen pieces was doing business on the grand scale.

In 1764 the population of Ossett was about 450 mainly living at or close to the existing town centre but with other small settlements in other locations including Low Common. In the town’s Market Place – a Victorian place name –stood the Grammar School, established in 1737-38 as an elementary school and rebuilt in 1834. Around this time James Hargreaves developed the Spinning Jenny which, unlike previous spinning machines, could spin a large number of threads at once. This and the development of the Arkwright waterframe and Crompton’s spinning mule meant that handloom weavers were guaranteed a constant supply of yarn, full employment and high wages.

This period of prosperity for handloom weavers was not to last very long and by 1785 Edmund Cartwright had invented a weaving machine which could be operated by horses, a waterwheel or a steam engine. The power loom took a while to become established and even by 1800 only a few hundred were in operation in Britain. However the decline of the handloom weaver was inevitable when the news became widespread that an unskilled boy could weave three and a half pieces of material on a power loom in the time a skilled weaver using traditional methods could weave only one.

Those who owned or worked the power loom were to become prosperous and the home handloom cottage industry continued to decline as the demand for cloth produced by handloom weavers lessened. Those who still found masters willing to employ them had to accept far lower wages than in the past. The old order had given place to the power loom – an innovation that was long and sorely resented by the old weavers.

But Ossett folk through the ages are Yorkshire through and through and know that where there’s a will there’s a way. They also know right from wrong and in spite of what misfortunes are thrown at them they find that way.

This website, ossettheritage.co.uk is here to freely share whatever I have researched and written about the history of Ossett over the last fifteen years or so. In the past my research has been freely given, but in common with most other Ossett historians I will not countenance individuals misrepresenting and taking credit for research which is not theirs. This website is here to ensure that the people of Ossett can choose for themselves what they wish to see of the history of their town and not what some others think they should or should not see.

The website includes data, photographs and sketches from a number of sources which will be acknowledged if they are known. If copyright is an issue in regard to any of the content then please contact me.

Ossett does not have an official coat of arms but this design has long been seen as an unofficial coat of arms. The design features the three principal industries of the town: wool and shoddy mills, coal mining and agriculture. The sheep signifies the importance of wool and the white rose is the symbol of Yorkshire. The Latin transcription, attributable to Ossett Grammar School headmaster Mr. M. Frankland who joined the school in 1881,more or less means “useless things made useful by skill”. It is a reference to turning rags into mungo or shoddy – one of Ossett’s major industries in days gone by.

Ossett does not have an official coat of arms but this design has long been seen as an unofficial coat of arms. The design features the three principal industries of the town: wool and shoddy mills, coal mining and agriculture. The sheep signifies the importance of wool and the white rose is the symbol of Yorkshire. The Latin transcription, attributable to Ossett Grammar School headmaster Mr. M. Frankland who joined the school in 1881,more or less means “useless things made useful by skill”. It is a reference to turning rags into mungo or shoddy – one of Ossett’s major industries in days gone by.