Alfred Naylor was born in 1893 in Ossett, the son of the sixth child and and fifth son of colliery banksman Bennett Naylor and Annie (nee Clark), who married in 1874 in the Dewsbury Registration District.

In 1901, Bennett and Annie and their eight children, seven boys and one girl, aged between 4 and 26 years of age, were living in a three-roomed home, close to the Prince of Wales public house on South Parade, Ossett. Bennett and his children were all Ossett born and his wife was born in Wakefield.

In 1911 the family were living at the same home with four of the children, including 18 year old Alfred who, like his father was working at the local colliery. Bennett and Annie had ten children in total, but two had died before April 1911.

At the outbreak of WW1 in 1914, Bennett and Annie had seven sons aged between 17 and 40 years, all of whom would probably have been served notice for national service, even though some may subsequently have been exempted due to the nature of their occupations. At least one son, Clarence Naylor (born 1896) did serve in the army and after suffering from gas poisoning, was recalled and then stationed in Ireland.

At the time of Alfred Naylor’s death in 1918, his widowed mother Annie Naylor, was living at Denholme Drive, Ossett. Alfred’s father, Bennett Naylor died in early 1915 aged 61 years.

The 2nd/4th Battalion of the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry was formed at Wakefield on the 30th September 1914 as a second line unit. On the 1st March 1915, the Battalion moved to Bulwell and was attached to 187th Brigade in the 62nd (West Riding) Division. They moved in April 1915 to Strensall, York and in May to Beverley, going on in November to Gateshead, then in January 1916 to Larkhill and June 1916 to Flixton Park near Bungay. The Battalion moved again in October 1916 to Wellingborough and landed at Le Havre on the 15th January 1917.

Private Alfred Naylor was killed on the 28th September 1918 when 62 (West Riding) Division were involved in heavy fighting to recapture the French village of Marcoing, which had been occupied by the Germans since March 1918.

“At 5.20 am on the 27th September 1918, the 1st and 3rd Armies attacked with IV, VI, XVII and Canadian Corps on a 21 km front from Gouzeaucourt to Sauchy-Lestrée. The vital point of the attack was the Canal du Nord near Moeuvres. On the VI Corps front the Guards Division and 3 Division crossed the canal in the face of strong machine gun fire. 62 Division started their move forward at 8 am, following close behind the reserve brigade of 3 Division. There was heavy fighting all day and by 8.30 pm 3 Division had withdrawn and 62 Division held a line just east of Ribécourt.

In the early hours of the 28th September 1918, attacks were resumed towards Marcoing and Masnières. Fierce fighting continued all the day, and by 6 pm, Marcoing had been taken, together with the trenches on the east side of the St Quentin Canal.

On the 29th September 1918, the attack was renewed with Masnières and Rumilly as the objectives. By noon, Masnières had been recaptured by the 62nd (West Riding) Division and cleared, but because of fierce opposition Rumilly was not taken that day.” 1

The “Ossett Observer” 2 had this short obituary for Private Naylor:

“Private Alfred Naylor (25), K.O.Y.L.I., a single young man whose mother resides at South-terrace, South-parade, Ossett, is reported to have been killed on September 29th 1918. He enlisted in June 1916, and previously worked at Old Roundwood Collieries. He was a member of the South Ossett Wesleyan Sunday school. He has two brothers serving in the army; Fred, at present on leave from Salonika, and Clarence, who after having suffered from gas poisoning in France, is now stationed in Ireland.”

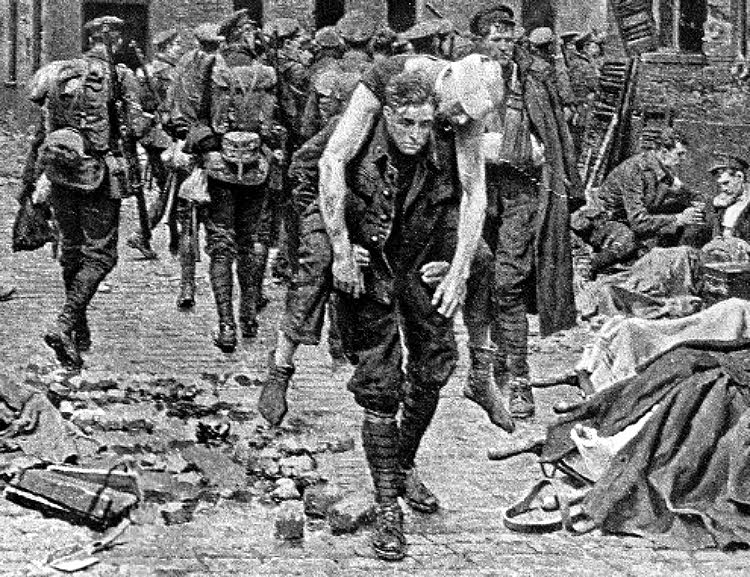

Above: British troops in Marcoing village in 1917, before the Germans took the village in the 1918 Spring Offensive. It was taken again by the British in late September 1918.

Private Alfred Naylor was awarded the British and Victory medals indicating that he did not serve overseas before the 31st December 1915. He died on the 28th September 1918, aged 25 years and is buried at grave reference C. 39. at the Grand Ravine British Cemetery, 3 Havrincourt, Pas de Calais, France. Havrincourt is a village approximately 10 kilometres south west of Cambrai and 3 kilometres south of the Cambrai to Bapaume road (N30).

Havrincourt village was stormed by the 62nd (West Riding) Division on 20 November 1917. It was lost on 23 March 1918, but it was retaken on 12 September by the 62nd Division, who held it against a counter-attack the following day.

Grand Ravine British Cemetery consists of three rows of graves. Row B was made by the 62nd Division Burial Officer in December 1917, and Rows A and C by the same officer in October 1918.

The cemetery contains 139 First World War burials, 11 of them unidentified.

As a postscript to this biography for Private Alfred Naylor it is perhaps worth mentioning the famous “The Incident at Marcoing”, which took place on the same day and the same place that Alfred Naylor died on the 28th September 1918:

It was September 28, 1918 and the fighting had been exceptionally heavy that day. Private Henry Tandey of the 5th Duke of Wellington’s (West Riding Regiment), had been killing Germans throughout the day, but when a wounded enemy soldier limped into his gun sights, Tandey held his fire. The German was clearly wounded, and though Tandey took aim, he could not bring himself to shoot the wounded man. The wounded soldier nodded in gratitude and disappeared into the fog. The incident at the French village of Marcoing was over quickly, but one that the German soldier would never forget and that Henry Tandey wouldn’t recall for some 20 years. During the fighting on that day the English private would single-handedly destroy a German machine gun nest, lead a bayonet charge on a far larger German force and, for his bravery, win the Victoria Cross. Private Henry Tandey was by anyone’s account a true hero. That German soldier was Adolf Hitler.

Henry Tandey was born in Leamington, Warwickshire, on August 30th, 1891, son of former soldier James Tandey. After a difficult childhood, part of which was spent in an orphanage, he became a boiler attendant at a hotel in Leamington before enlisting in the British Army, joining the Green Howards Regiment in August 1910 and embarking on an adventurous military life. He was wounded in the leg during the Battle of the Somme and, when discharged from a military hospital in England, was wounded at Passchendaele in November 1917. After his unit was disbanded in July 1918, he was attached to the 5th Duke of Wellington Regiment from 26th July to 4th October 1918. It was at this time Private Tandey was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal for determined bravery at Vaulx Vraucourt on August 28, the Military Medal for heroism at Havrincourt on September 12th and Victoria Cross for conspicuous bravery at Marcoing on 28th September 1918.

Years later he discovered he had spared an Austrian Corporal named Adolf Hitler. Hitler himself never forgot that pivotal moment or the man who had spared him. In 1937 Hitler was made aware of a Fortunino Matania painting and his staff managed to obtain a print of the Italian painting, showing Tandey carrying a wounded Allied soldier on his back, which Hitler hung with pride on the wall at his mountain top retreat at Berchtesgaden. The painting was commissioned by the Green Howards Regiment from the Italian artist in 1923, showing a soldier purported to be Tandey carrying a wounded man at the Kruiseke Crossroads in 1914, northwest of Menin. The painting was made from a sketch, provided to Matania, by the regiment, based on an actual event at that crossroads. Hitler also ordered his staff to track down Tandey’s service records.

Above: A detail from the painting by Fortunino Matania of the 2nd Battalion, Yorkshire Regiment, Green Howards at Menin Crossroads in October 1914 showing Henry Tandey carrying a wounded comrade. What is beyond doubt is that Hitler actually had a copy of this painting. It was given to him because it was thought that his regiment and the Green Howards had both been in this action.

He showed the print to British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain during his historic visit in 1938 and explained its special significance. The Führer seized that occasion to have his personal gratitude relayed to Tandey, which Chamberlain conveyed via telephone on his return to London from that most fateful trip.

Henry Tandey left military service before the start of World War II and worked as a security guard in Coventry. His “good deed” haunted him for the rest of his life, especially as Nazi bombers destroyed Coventry in 1940 and London burned day and night during the Blitz. “If only I had known what he would turn out to be. When I saw all the people, woman and children, he had killed and wounded I was sorry to God I let him go,” he said before his death in 1977 at age 86. At his request, he was cremated and his ashes buried in the Masnieres British Cemetery at Marcoing, France, on the 23rd May 1978, by his undertaker Pargetter and Son.

Sadly, the story is not true. Detailed research has shown that at the Menin Road in 1914, Tandey’s battalion was evacuated two days before Hitler’s unit, the 16th Reserve Bavarian Infantry Battalion arrived. So Hitler never witnessed the event in the painting. But what about the all important date on September 28, 1918? The 16th Reserve Bavarian Infantry Battalion had been moved from Favreuil on the Somme near the French Belgian border to the Wyschaete quarter, near Marcoing on September 17, 1918. But Hitler did not move with his unit.

German Army records show that Adolf Hitler was on home leave from September 10th to September 27th, so would still have been in transit on September 28th. Also his unit was actually positioned some fifty miles north of Marcoing where Henry Tandy’s valiant action took place. As Lieutenant Colonel Neil McIntosh, Green Howards Museum Curator and regimental secretary said after carrying out the research, “It is a delightful story, but unfortunately we have proved it to be complete hogwash.”

CWGC heastone photograph courtesy of Mark Smith

References:

1. British 62nd Division in the Great War

2. “Ossett Observer”, October 19th 1918