The Armistice between the Allies and Germany, which came into force on the 11th November 1918, did not mark the formal end of the war and it was only on the 28th June 1919 that the signing of the Treaty of Versailles restored peace. Meanwhile, in the United Kingdom, war-time controls, including rationing and the state control of mines and railways, remained in force. Housewives preparing for Christmas found that greengrocers had no apples and grocers had no raisins or candid peel. These, however, were minor inconveniences as the town celebrated its first Christmas at peace since 1913. Hopes that the influenza epidemic was coming to an end were dashed in the new year. In March there was a fresh outbreak in Ossett which closed the town’s schools. The following month saw another closure, that of the Town Hall’s National Kitchen following a fall in the demand for its meals. This was despite the fact they were good value for money.

Above: The signing of the November 11th 1918 Armistice. it came into force at 11:11 a.m. Paris time on 11 November 1918 (“the eleventh minute of the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month”) and marked a victory for the Allies and a defeat for Germany, although not formally a surrender. Henry Gunther, an American, is generally recognized as the last soldier killed in action in World War I. He was killed 60 seconds before the armistice came into force while charging astonished German troops who were aware the Armistice was nearly upon them.

Following the armistice Parliament was dissolved and Ossett, now included in the Batley rather than the Morley constituency, prepared to vote in the first general election since 1910. With the war-time political truce at an end, local voters had a choice between two candidates: Gerald France, who stood for the Liberal-Conservative coalition, and Ben Turner, who represented Labour. Both men were well known in the area, Turner as a trade union leader and Mayor of Batley, and France as the Liberal MP for the old Morley constituency. During their election meetings in Ossett France had to explain why he had opposed votes for women, while Turner had to deal with accusations that as a pacifist he was lacking in patriotism. On polling day, 14th December, the “Ossett Observer” carried the two men’s final appeals to the electorate. France’s advertisement posed the question, “Is this new Parliamentary Borough to be disgraced by having for its first member a PACIFIST?” Turner claimed “a vote for Coalition is a vote for Conscription, for Vested Interests, for Landlordism, Slumdom, Sweated Wages, and the old tyranny of things.” He appealed to voters to support their “own neighbour and friend and Human Justice and Social Freedom.”

Although voting was slow on polling day, 75% of the resident voters went to the town’s four polling stations. For the first time women voted in a parliamentary election. The “Ossett Observer”, which was surprised at the number of women who turned out, reported that very often wives and husbands voted together. The result of the election was not known for more than a fortnight as the votes of absentee servicemen had to be returned and counted. When the count for the Batley constituency was completed, Gerald France had 13,519 votes to Turner’s 12,061. Nationally, the Coalition won the election and Lloyd George remained Prime Minister.

Ossett’s voters returned to the polls in March 1919 when there was an election for a County Councillor. Both the Labour and Coalition candidates issued election addresses dealing with housing, education and the treatment of disabled soldiers, but the contest did not arouse much interest and only 40% of the electorate voted. Robert Dixon Smith won the seat for the Coalition with 1,721 votes to Henry Wilkinson’s 1,012. Another local election followed in April when four people stood for Ossett’s two places on the Dewsbury Board of Poor Law Guardians. Two of the candidates were women, Mrs Emma Hanson and Mrs Janet Booth. Emma Hanson was elected together with the other Coalition candidate, Mr P. H. Wilson, and became the first woman elected as a public official in Ossett.

The changed composition of the electorate as a result of the 1918 Reform Act was recognised by Ossett’s Liberal Club when it admitted women to its membership. By the time of its annual general meeting in February 26 of its 245 members 34 were women and four of them were elected to the club’s committee. One Liberal, Mr B. P. Wilson, welcomed the change with the words, “no wiser step had ever been taken the club’s history.” Although the Conservatives were for the moment political allies of the Liberals, Ossett’s Conservative Club seems to have remained a male stronghold.

With the signing of the Armistice, the demobilisation of the armed forces began. Initially the government’s plan was to release workers essential to the economy first. As part of this plan a sub-committee of the Ossett Chamber of Commerce put forward the names of local men for demobilisation. However, in February 1919 the Chamber was notified by the Controller-Director of Demobilisation that no more names would be accepted for the army. This was because the government’s scheme had been so unpopular with the armed forces that it had been abandoned and a plan based on the principle of “first in, first out” had been adopted in its place. While servicemen were being demobilised, absolutist conscientious objectors such as Ossett born Eli Marsden Wilson were being released from prison and discharged from military service. Some in Ossett opposed the return of conscientious objectors to civilian life, particularly as they were being freed before the demobilisation of many servicemen. When the matter was raised at the March meeting of the Trades and Labour Council, it voted for both the release of conscientious objectors from prison and the rapid demobilisation of the armed forces.

Demobilisation could not come soon enough for many servicemen: by February 1919 one Ossett soldier, Donovan Glover, was “very sick of the Army and longing to be home again”. Gradually, however, the number of demobbed servicemen in the town increased. To welcome them home, the different religious denominations began to hold social events. Among them were the Wesleyans of Wesley Street who in March treated 40 former servicemen to a pie supper and a social evening. One result of the return of so many soldiers from abroad was an increase in the number of foreign coins in circulation. This was particularly unwelcome to Ossett Corporation as customers of its gas works began to use large numbers of such coins in their slot meters.

Above: German WW1 Prisoner of War Camp.

Among the men returning to Ossett were some who had been German prisoners of war and several of them told their stories to the “Ossett Observer”. All had been poorly fed and many had been put to work. A number, like Willie Stephenson, had been sent to coal mines while Harold Moss had been more fortunate as he had been assigned clerical work in his camp. Like some other prisoners, Moss had met Germans who had treated their captives well. Overall, however, he had found the German guards “violent and ill tempered” and their treatment of prisoners “vile”. Private Claude Hainsworth, who had been a prisoner for three years, had a simple explanation for this behaviour: all the good Germans were dead and the survivors were “savages of the dark ages.”

Hainsworth’s opinion of the Germans was contradicted by Sergeant Willett who was serving with the British army of occupation in the Rhineland. In extracts from his letters printed in the “Observer” he commented on the friendliness of the Germans he had met. They were treating the British troops “pretty decently” and he wondered “if a lot of the atrocities laid at their door” had not been press propaganda. Willett’s words provoked an angry response from readers. Lieutenant Westwood, who had also been in the Rhineland, wrote to the “Observer” to say the Germans hated the English “like poison” and had behaved “brutally” not only towards their prisoners of war, but also French and Belgian civilians.

Although the Armistice brought an end to the fighting in France and Belgium, it did not end the toll of deaths among Ossett servicemen. Families who had thought their loved ones were safe instead received news of their deaths. Among the dead was Private Arthur Dews who was serving on the Western Front when he was mortally wounded by the accidental explosion of a grenade on Armistice day. Other soldiers were the victims of illnesses. Pneumonia killed Private Jim Elliott at Cherbourg and Driver R. E. Pennington of the Royal Engineers at Salonika. Other families had news that relatives who had been reported as missing or as taken prisoner were in fact dead.

Although the Armistice brought an end to the fighting in France and Belgium, it did not end the toll of deaths among Ossett servicemen. Families who had thought their loved ones were safe instead received news of their deaths. Among the dead was Private Arthur Dews who was serving on the Western Front when he was mortally wounded by the accidental explosion of a grenade on Armistice day. Other soldiers were the victims of illnesses. Pneumonia killed Private Jim Elliott at Cherbourg and Driver R. E. Pennington of the Royal Engineers at Salonika. Other families had news that relatives who had been reported as missing or as taken prisoner were in fact dead.

At least one family had the added distress of receiving conflicting reports about the fate of a missing serviceman. Mrs Summerscales’ husband, Private George Summerscales, had gone missing in action in France in May 1918. In December a former British prisoner of war wrote to her that George had died in hospital about five weeks after being captured. However, in June 1919 she received official notification that he had in fact been killed in action.

Left: Private George Summerscales.

Among the returning servicemen were some who were disabled. Although these men could claim a disability pension, it was only a small amount and the government expected them to turn to charity for help. This happened in Ossett in March 1919 when a benefit concert was held in the Town Hall to aid three veterans with disabilities: Sergeant Woollen, Private Boswell and Private Clapham. It was to assist such men that the Discharged Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Association had been formed. At the first annual general meeting of its Ossett branch in December 1918, it was reported its membership included 130 discharged men and that more than 100 claims for assistance had been successfully dealt with.

The absence of men on military service had a disruptive effect on the lives of some families. Harry Boocock returned home after four years in the army to find his fourteen years old son was, in his words, “quite beyond his control” and had become a “thief” and a “liar.” During Walter Rayner’s absence in France, his wife, who had been unwell, had kept their thirteen years old daughter, Esther, away from school to look after her four younger siblings. When Rayner appeared before the Borough Court because of his daughter’s absenteeism, he explained Esther had been a “mother” to the other children and a “housekeeper” to him since his return.

The social impact of the war also led to an increase in the number divorces. One of those who divorced in 1919 was Willie Day of Gawthorpe. When he had enlisted at the start of the war, his wife had left him and let him know she never meant to live with him again as she had ‘a good lad to look after her’. The war also saw an increase in the number of cases of bigamy before the courts. Ada Womersley married a soldier, Private James Clark, at Dewsbury in September 1918. Unfortunately, as Ada’s relatives quickly discovered, Clark already had a wife and three children in Wales and at Leeds Assizes in March 1919 he pleaded “guilty” to a charge of bigamy and was sentenced to two months imprisonment.

If the war created conditions in which bigamy was easier, it also encouraged prostitution as the Dean family found to its cost. Eighteen years old Ida Dean left her home in the autumn of 1918 to become a prostitute when a friend told her how she could earn money without working. She appeared in Ossett Borough Court in January 1919 charged with vagrancy when the police found her asleep on a bench outside Ossett Town Hall one night. Her mother told the magistrates, “we have tried her all ways, with kindness and hitting her.” Ida was bound over for two years on condition she entered a rescue home and was supervised by a probation officer.

As Ossett’s servicemen were returning home, most of the Belgian refugees who had been in the town since October 1914 were preparing to leave. In February a crowd gathered in the Market Place to see off a party of 42 refugees who were accompanied to Kirkgate Station in Wakefield by the Deputy Mayor, Alderman H. Robinson, Councillor W. Moys and Mr C. Rhodes, the Deputy Town Clerk. At Kirkgate they were joined by other refugees and their train to Hull left the station amid the waving of Belgian flags and Union Jacks. The “Wakefield Express” noted a number of the children from Ossett could only speak English and that it was “of a fairly marked Ossett brand.” The last of the refugees left the town in June 1919. Mr and Mrs Seyers had intended to stay in Ossett, but when Mr Seyers was offered his old job back with good wages and a rent-free house the couple decided to return to Belgium. Writing to Mr R.P. Shaw, Seyers thanked the people of Ossett for the hospitality they had shown and added, “I am again in Ghent, but my heart is still with my friends in Ossett.”

Above: Belgian refugees working in Ossett circa 1915.

Plans for the future occupied the minds of many in Ossett after the Armistice. As preparations for the Paris peace conference started, the Borough Council approved a resolution demanding that the Kaiser should be put on trial and that Germany should pay the cost of the war. The British war effort had been financed in part by borrowing and in January 1919 the last War Bonds went on sale in Ossett. However, even with the prospect of peace, the government still needed to borrow and in July the town took part in the Victory Loan campaign. Initially Ossett was set a target of £10 a head, a total of £145,000, but the borough’s War Savings Committee lowered the figure to £5 a head. In spite of the best efforts of the Committee, there was no public enthusiasm for the campaign and even the reduced target was not met.

Some of the money the government hoped to raise through the Victory Loan was to be spent on new housing. Ossett’s housing needs had been discussed in the town during the war and in November 1918 the Borough Council identified two plots of land for council housing, one at the corner of Teall Street and Spa Street and the other in Northfield Lane. The question of what types of houses should be built caused some debate. The Council wanted houses with three rooms downstairs and three bedrooms, a toilet and a bathroom upstairs. Critics of the Council’s scheme claimed such houses would be so expensive to build that their rents would be too high for working class families. A member of the Chamber of Commerce, Mr J. H. Glover, put forward an alternative scheme for smaller houses with two rooms downstairs and one large bedroom upstairs. However, the Council went ahead with its plans, although building work on Ossett’s first 49 council houses had not started by the time the peace treaty was signed. The question of rent levels was solved by the introduction of subsidies under the 1919 Housing Acts which enabled council housing to be let at uneconomic rents. By June 1919 the Council was considering building more houses at Sowood Lane, Storrs Hill Road, Wesley Street and Swithenbank Street. John Oldroyd, in a letter to the “Observer”, suggested the new houses should have gas heating rather than coal fires. Gas, he argued, was cheaper and less polluting than coal as well as creating less work for the housewife than coal fires.

The future of British industry was a topic which particularly concerned the Chamber of Commerce. At its meeting in January 1919 its President, Mr J. H. Gibson, read a paper on “Some Problems of Commercial Reconstruction.” His conclusions were not very encouraging. He pointed out that although the economy appeared to be booming, the real test for it would come when government controls and borrowing were reduced. He also warned it might be difficult for Britain to adjust to peacetime conditions because she had lost her industrial supremacy to the United States and Germany before the war. Their productivity was higher than Britain’s, he said, and this was partly because they invested more in scientific education than Britain.

Of more immediate interest to the Chamber of Commerce than foreign competition was ownership of the rail and mining industries. The Chamber was divided over the possible nationalisation of the railways, some members being for and others against. During the discussion, Mr J. Fitton spoke of the benefits the electrification of the railway system would bring and also the convenience of motor waggons for transport. Members of the Chamber were also divided over the question of the ownership of the coal industry. Mr J. H. Gibson, who had once been in favour of its nationalisation, now supported private ownership. In his opinion, “the great things for the country were personal initiative, hard work, and thrift – qualities which had made Great Britain, and they would not get those results from Government officials whose life was made too easy.” He did, however, favour the nationalisation of mineral rights rather than allowing them to remain in private ownership.

The British economy still depended on coal, but it took time to restore production after the Armistice. In January 1919 the Chamber of Commerce’s trade report put output from the town’s collieries at 40% of its pre-war figure. Local manufacturers, the report said, were “just able to keep going”, but it was expected that the return of miners from the armed forces would ease the crisis. However, coal production was hit by a one-day strike of Yorkshire miners in January over working hours. The miners’ demand was quickly granted by the Coal Controller, a sign of just how serious the coal shortage was. The following month miners across the country voted to support the Miners’ Federation’s demand for a working day of six hours, a 30% increase in wages and the nationalisation of the mines. Among the pits balloted was Ossett’s Old Roundwood Colliery where 697 men voted for a strike, 82 voted against and 102 abstained. To avoid a coal strike, the government appointed the Sankey Commission to examine the miners’ demands. In July, however, the Yorkshire miners went on strike over pay and hours. The dispute lasted into August causing mills in the town to stop work and an increase in unemployment in the borough.

Above: Coalface worker in a U.K. colliery circa 1919.

Not content with expressing his views at the Chamber of Commerce, Mr G. H. Wilson sent the “Ossett Observer” a poem on the strikes which the paper printed. It is too long to quote in full, but part of it reads:What can be done to stem this great unrest

Which tends to sap the vitals of our race?

Is it for nought that men gave of their best,

Even their lives? Whose sacrifice we trace

In blighted homes, where wives and mothers weep.

And through long nights their mournful vigils keep.

The war dead were commemorated in different ways in Ossett in the months following the Armistice. Mr and Mrs Arthur Jessop, who had lost their only son, gave £1,000 to endow a bed at Dewsbury Infirmary. The Green Congregationalists placed the framed photographs of servicemen belonging to the church in their Sunday school. Ossett Grammar School decided to honour the 17 old boys who had died with a plaque in the school hall. Holy Trinity Church resolved to have a peace memorial in the form of an extension to the chancel. Christ Church’s memorial, which was to include the names men of all denominations from the parish who had fallen, was to be in the new burial ground in Manor Road.

The movement to provide a memorial to all of Ossett’s war dead had begun in 1917. A number of schemes had been put forward and a public meeting at the Town Hall in January 1919, which was was attended by 120 people, decided in favour of an ambitious project for a library, art gallery and museum set in a public park. The following month the War Memorial Committee started a campaign to raise the £20,000 needed for the project. The Mayor, Alderman G. F. Wilson, opened the subscription list with a donation of £500 on behalf of Messrs Wilson and Brothers. Other residents were less generous and in March Mr G. H. Wilson wrote to the “Ossett Observer” to complain about the “feeble” response to the appeal and to call on his fellow townsmen to respond “to the heroic sacrifices” made by “our gallant heroes.” Although there were those who wanted the War Memorial Committee to abandon its scheme, the Committee decided to persevere with its fund-raising campaign.

Above: British WW1 tank, like the one offered to Ossett by the National War Savings Committee.

While the War Memorial Committee was trying to raise money, another committee, the National War Savings Committee, offered the town a tank to mark its contribution to the war time savings campaigns. At its meeting in April 1919 the Borough Council decided to accept the gift, although some councillors had reservations about the costs of preparing a site and then maintaining the tank. The space between the Liberal Club and the Technical School was suggested as the most suitable site, but later in the year the Council, having reconsidered the gift, decided to refuse it. However, if Ossett did not have a tank, it did have an exhibition of German war relics in the Town Hall in May. Among the items on display were a machine-gun, an automated grenade thrower, a gas cylinder, an anti-tank gun, a breast plate and a helmet.

Following the signing of the Treaty of Versailles, there were official thanksgiving services on Sunday 6th July in the town’s Anglican churches and the event was also marked at the Nonconformist places of worship. In his sermon at St Mary’s, Gawthorpe, the Rev. G. H. Harvey, mentioned the war-time leadership of Germany. The men who had “guided and inspired” the “tremendous evil” of the war had been “repudiated by their own nation” and he predicted “never more would the world allow such horror to overshadow it.” That night a public service of thanksgiving attended by over 2,000 people was held at the Town Hall. The Mayor, Alderman Wilson, presided and Anglican and Nonconformist ministers took part. Music was provided by the Ossett Orchestral Society and the singing of the National Anthem was followed by hymns including “All People That on Earth Do Dwell” and “Now Thank We All Our God.”

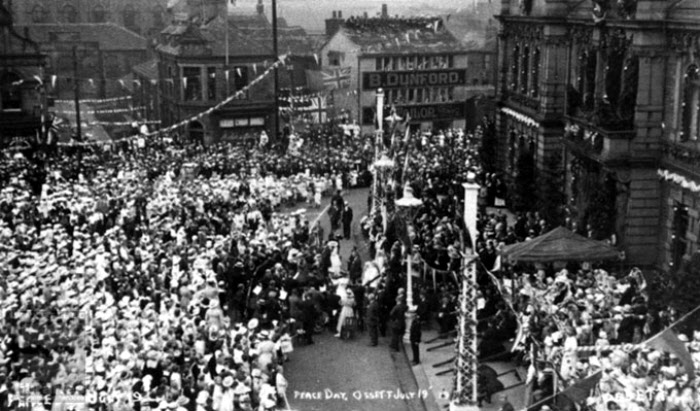

Above: Peace Day Celebrations, Ossett in July 1919.

After the thanksgiving came the peace celebrations. These had been planned by the Peace Celebrations Committee which had set out in May 1919 to raise £2,000 for three days of festivities. There were those who thought £2,000 was far too much to spend. One was Mr J.H. Glover who believed half the amount would be sufficient and certainly did not want money wasted on what he called “tomfoolery.” In fact, the Committee raised considerably less than its target, £1,300, but still provided three memorable days on Saturday 19th July, Monday 21st July and Tuesday 22nd July. During the celebrations the Town Hall, the Market Place and the streets were decorated with flags and streamers and the Pickard Memorial Fountain was adorned with green shrubs.

On Saturday, three thousand children gathered in the Market Place, together with several thousand spectators, to hear the Mayor read the King’s proclamation of peace. After the National Anthem and several hymns had been sung and speeches made, the children had tea in the Town Hall and in nearby schools. Tea was followed by sports and, in the evening, there were fireworks and a large bonfire topped by effigies of the Kaiser and his son, the Crown Prince, was lit by the Mayor. On Monday morning, when 250 veterans staged an impromptu march to the Town Hall carrying a banner inscribed, “Lest We Forget”, the Mayor took the salute and, after a bugler sounded the last post, the men saluted the Union Jack. Later in the day veterans, their wives and sweethearts, some 1,500 people, had tea in the Town Hall and Southdale School. Later, “The Inimitables”, a Wakefield troupe of Pierrots, provided “endless fun and merriment” in a show at the Town Hall. Finally, on Tuesday, 1,400 old people and war widows had tea in the Town Hall and at Southdale School followed by an evening entertainment at the Town Hall. Among its highlights was a Jazz band made up of an unlikely combination of corporation officials and a councillor. Unfortunately, the “Ossett Observer” did not name the councillor.