Jessie Jaggar was born in Ossett on 8th March 1888, the daughter of mungo manufacturer Robert Pickersgill Jaggar and his wife Elizabeth Jane (nee Petch) who married at Thirsk in late 1881. Jessie, the fourth born girl and the fifth of six children born to the couple, was baptised at Ossett Trinity Church on 1st April 1888. The family lived on Dale Street.

Robert Pickersgill Jaggar was the only brother of Joseph Jaggar, a rag, shoddy and mungo dealer who, in 1873-74 founded the Perseverance Mill on Dewsbury Road, Ossett. Joseph went bankrupt shortly afterwards in 1879.1

At the time of Jessie’s baptism in 1888, Robert and his family lived on Dale Street, but by 1891 they had moved to Greatfield. Robert and Elizabeth had been married for ten years and had five children, aged nine and under. The family had a domestic servant. In 1901, two of Jessie’s sisters were elsewhere, but a sixth child had been born to the couple who remained living at Great Field. The Jaggar family still had one servant.

Sadly, Robert Pickersgill Jaggar died on 4th May 1908, aged 50 years, and probate was granted to his only son, Howard, a mungo manufacturer, and his widow, Elizabeth Jane. Robert’s estate was worth £13,311. In 1911, Elizabeth Jane was still living at Greatfield, Ossett now with four of her daughters, two of whom were teachers. Jessie, now aged 23, was also a teacher, working as an assistant mistress to the Principal at Olton College School for Girls in Warwickshire. In the same year her only brother, Howard, a mungo manufacturer, was staying in a Southport hotel and in August 1911 married Southport girl, Catherine Milne, at Ossett Holy Trinity Church.

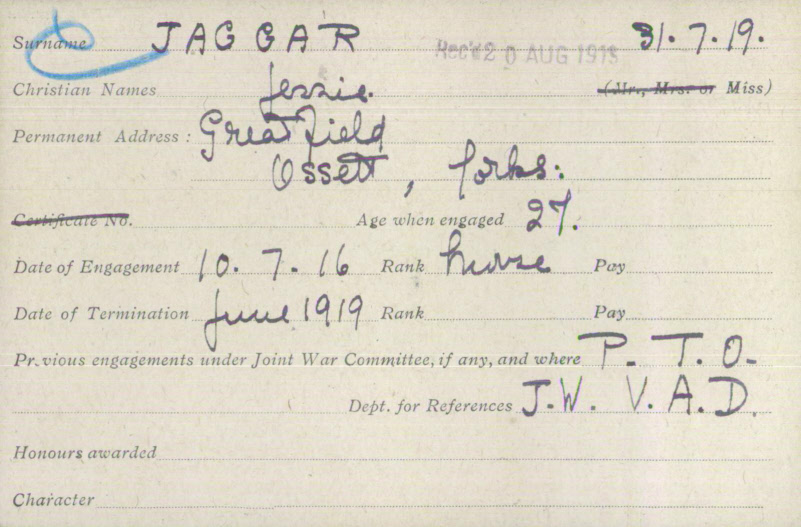

On 10th July 1916, Jessie Jaggar, aged 27, of Greatfield, Ossett, was engaged as a Volunteer Nurse in the Voluntary Aid Detachment and was posted to the Kitchener Hospital, Brighton. The date of her engagement is just 10 days after the first day of the Battle of the Somme when approximately 60,000 British men were wounded, including almost 20,000 who were killed. In the earlier part of WW1, the Kitchener (and the Brighton Pavilion) was a hospital used largely for the treatment for Indian troops wounded in the conflict. No female nurses were employed at the Kitchener at that time.

Above: Nurse Jessie Jaggar’s WW1 Service Record.

By November 1915 the Kitchener Hospital was no longer used to treat Indian soldiers and from then on the buildings were used for British wounded, the majority being amputees. In November 1916, Jessie was transferred to the 42nd Hospital in Salonika where she remained until 2nd November 1917. Jesse would have sailed, probably from Southampton, via Marseilles and perhaps aboard a Hospital ship, arriving in Salonika up to a month after embarkation. The fighting in Salonika was spasmodic but fierce and the casualties to the 600,000 French, British and Serbian troops were high and severe.

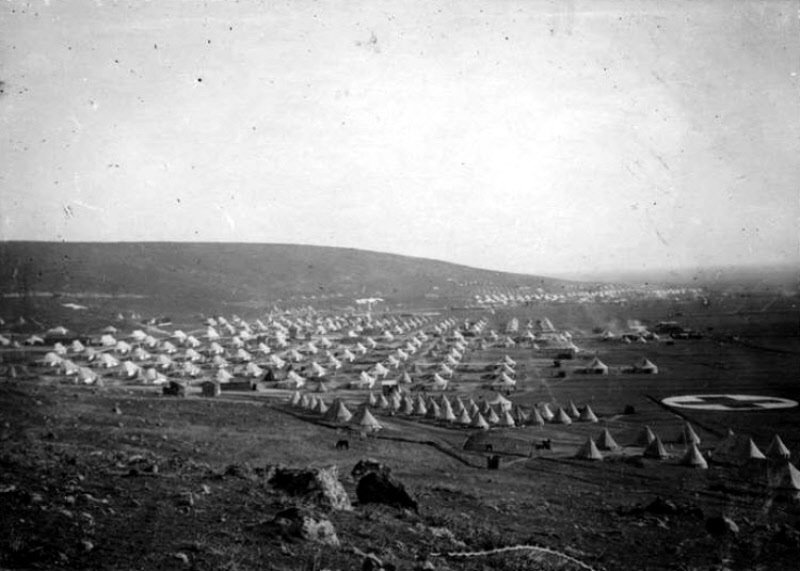

Above: Royal Army Medical Corps, 37th General Hospital at Salonika during WW1. The hospital was bombed by German aircraft on the 12th March 1917, and two nurses and four RAMC orderlies were killed, despite the hospital being clearly marked. Nurse Jessie Jaggar served in the 42nd General Hospital and it is likely that there were strong similarities between the two field hospitals.

The life of nurses and their patients serving in Salonika (Greece) is described in this excellent description below:2

“But they found themselves in a land of harsh extremes, and for those nurses from a comfortable Edwardian middle-class background, it must have been particularly shocking. They lived in small tents, and in an area where water was in short supply, they used canvas bowls or baths to wash. Perhaps expecting a hot climate, rather like Egypt, they must have been dismayed at what they found. The winters were harsh and very cold, with freezing winds blowing down the river Vardar and spreading across the vast empty plains. The terrain was hostile and unrelenting. At night, the nurses in their freezing tents soon discovered that if they failed to wrap a garment or towel around their heads, their hair would freeze to the pillow.“

“But that was just the winter – the horrors and discomforts of the summer were much worse. Flies and ants were everywhere, touching everything, whilst there were also centipedes, sand-flies, scorpions, wind and rain. ‘Creepy-crawlies’ would get into the tents at night – mice, lizards, the occasional snake – whilst the sweltering July heat would generate copious perspiration and a permanent thirst. But more dangerous and lethal than any of these were the dreaded female Anopheles mosquitos, which have a vicious liking for human blood.“

“Illness was rife and the majority of the troops who served in Macedonia became infected at one time or another. The nurses spent more of their time tending to those with malaria and dysentery than the wounded. The nature of the marshy terrain, peppered with stagnant pools, combined with the baking heat in the summer to create one of the worst areas in Europe for malaria. Malaria seriously impinged on the effectiveness of the BSF because it sapped the energy and strength of all the men who contracted it, while dysentery was another serious killer which claimed many soldiers’ lives, as well as some of the nurses caring for them.“

“The nurses started to wear mosquito veils, gloves which reached their elbows and boots – hardly comfortable in the summer heat – to prevent being bitten. The effects on manpower were devastating – in total, the British suffered 162,517 cases of the disease, and in total 505,024 non-battle casualties. Without the supreme efforts of the medical organisations in Salonika – the Royal Army Medical Corps, the QAIMNS, the Red Cross and the Scottish Womens’ Hospitals – hardly a single man would have been fit to continue fighting. In total, non-battle casualties were up to 20 times the level of casualties in battle.“

“They would prepare wards, apply dressings, feed meals to the sick and wounded who couldn’t feed themselves, chat to the patients, comfort the dying and write letters home to next-of-kin. But nurses also had to deal with psychological suffering and ‘shell shock.”

Jessie’s next transfer, back to Blighty, would probably have come as a relief. Her service in Salonika came to an end on 2nd November 1917 and on 13th December 1917, perhaps after a break at home or convalescence after Salonika, she took up her next appointment at the Colchester Military Hospital.

Above: Colchester Military Hospital in WW1.

Colchester Military Hospital was able to treat about 221 patients in side rooms and eight traditional wards.

There follows a story of an Australian soldier, Cyrus Clarence Allsopp, who was just 19 years old when he enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force. Cyrus left Sidney in August 1916 and, after training in the UK, he was in the trenches on the Western front by late November 1916. He was wounded in June 1917 and hospitalised to Colchester for seven months, until early 1918 when he re-joined his regiment.

Nurse Jessie Jaggar, was posted to Colchester Military Hospital in mid-December 1917, just in time for Christmas 1917. It is possible to believe that they heard the same music, sang the same songs and joined hands to welcome in the New Year, which was to be the last year of the Great War. It is possible too that the volunteer British Nurse, Jessie Jaggar helped the volunteer Australian soldier, Cyrus Allsopp, to get through what was, in those moments, the biggest challenge of his life and to get well.

Cyrus was wounded again before the end of WW1, but he did return home, and he became a grandfather. Perhaps Nurse Jessie Jaggar played a small part in his life?

Here is an extract from the story of Cyrus Clarence Allsopp:3

Cyrus’s military record does not mention where in France and Belgium he fought however on 1st June 1917 he was wounded in action with gunshot wounds to his left thigh and left side. After a short time in a field hospital he was transferred to a military hospital in Boulogne, France. This took place 6 days before the 34th Battalions’ engagement in their first major battle at Messines in Belgium, so I believe he was near Messines at the time he was wounded. On 4 June 1917 he was transferred to Colchester Military Hospital in England.”

Cyrus’s military record does not mention where in France and Belgium he fought however on 1st June 1917 he was wounded in action with gunshot wounds to his left thigh and left side. After a short time in a field hospital he was transferred to a military hospital in Boulogne, France. This took place 6 days before the 34th Battalions’ engagement in their first major battle at Messines in Belgium, so I believe he was near Messines at the time he was wounded. On 4 June 1917 he was transferred to Colchester Military Hospital in England.”

“After 7 months of recuperating Cyrus was sent back to his Battalion, joining them on 9 February 1918. Just 2 months later on 16 April 1918 Cyrus was promoted to Lance Corporal Unfortunately only weeks after his promotion on 30 April 1918 Cyrus became ill and was once again transferred to the Colchester Military Hospital. His record does not state whether this was a result of his previous injury, or something else entirely, but he didn’t re-join his Battalion until 20 July 1918 so whatever illness it was – it was considerable.“

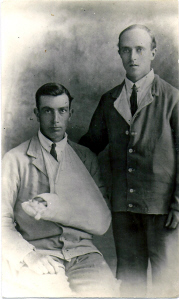

“Cyrus (left) was wounded just five weeks later for the second time on 29 August, 1918 with a gunshot wound to his left wrist and hand this time being invalided to the Cheltenham Military Hospital on 3 September 1918. He was finally discharged from hospital on 18 January 1919 and sent home via the “Ulysses” arriving 15 March 1919.”

Nurse Jessie Jaggar’s service in Salonika as a Voluntary Aid Detachment Nurse attached to Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service (QAIMNS) was acknowledged in 1920 when she was awarded the British and the Victory Medals. These medals were the same as those awarded to men who had served overseas during WW1 (The British Medal) and served overseas in a theatre of war (The Victory Medal). Research suggests that she was one of only a few Ossett women to have received the awards.

Volunteer Nurse Jessie Jaggar remained with her Voluntary Aid Detachment at Colchester until 13th June 1919 when she too returned home. Jessie, of Station Road, Ossett never married. She died in October 1966 and was buried at her local church, Ossett Holy Trinity, on the 6th October 1966, aged 78 years.

References:

1. Ossett History website

2. West Sussex & the Great War Project: www.westsussexpast.org.uk © Malcolm Linfield and West Sussex County Council