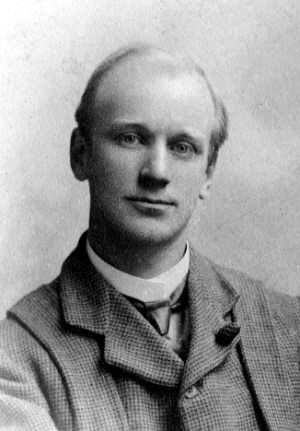

Eli Marsden Wilson was born on the 24th June 1877, the only son of Alfred Wilson and his wife, Emma (nee Marsden), who married in Ossett in 1865. Alfred and Emma Wilson had six children, all born in Ossett, and all girls apart from Eli. Alfred Wilson worked in the textile industry as a foreman beamer at the 1881 and 1891 census and the Wilson family lived first in Headlands, Ossett, moving to Runtlings Terrace, Ossett in the 1900s. The Wilson family was brought up in a supportive atmosphere of learning. The children were encouraged to take an interest in the arts and everyone played a musical instrument. Alfred Wilson himself played the cello, which was an unusual choice for Victorian Ossett.

By 1891, Eli Wilson was working as a clerk for a cloth manufacturer, possibly at the same mill in Ossett where his father was a foreman. Ten years later in 1901, he was working as an art master, presumably teaching at a local school. Wilson had attended Wakefield College of Art before moving to the Royal College of Art in London in the early 1900s, where he became a pupil of Sir Frank Short, an eminent painter and etcher.

In the June quarter of 1905, at Wandsworth in London, Eli Marsden Wilson, aged 28 years, married 33 year-old Hilda Mary Pemberton, the daughter of civil engineer Frederick Blake Pemberton. Hilda Pemberton was a was a decorative designer, painter and etcher in her own right. She was educated at Goldsmith’s College in London and as a student received silver and bronze medals from the Royal College of Art in recognition of her talents. The couple lived at 9, Faraday Road, Acton, London.

Wilson was doing well in London as an artist specialising in etchings, which saw a revival in the early 1900s. An etching called “The Market, Ossett” was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1905 and this was the first of seventeen pictures by Wilson exhibited at the R.A. Religiously, Eli Wilson had gradually moved away from the Wesleyan Methodism he was brought up with and he started attending Quaker Meetings, but had not been formally admitted to membership. He had also become a vegetarian, which although not common in the early 20th century, was well established. The Vegetarian Society dates back to the early 19th century and there was an overlap between the pacifist movement and the vegetarian movement, which may have influenced Wilson’s choice to become a absolutist conscientious objector during WW1.

As a married man, he was excluded from the first Military Service Act in early 1916, but became liable under the second Act in mid-1916. The Military Service Act of January and May 1916 introduced conscription for the first time in WW1 and the extension to the act in May 1916 deemed that all men aged between 18 and 41 years were eligible to be called up for military service. There were four clauses in the Act for exemption, one being the conscientious objection to the undertaking of combatant service.

A system of Local and Central Tribunals was arranged. Each registration district as would have a Local Tribunal or Tribunals, consisting of between 5 and 25 members each. Any person aggrieved by the decision of a Local Tribunal could make an appeal. Eli Marsden Wilson was married and aged 38 when the Military Service Act was introduced and no doubt to his horror, he was conscripted into the army in late 1916 when he was living in Acton. Wilson applied to the Acton Military Service Tribunal for exemption as a conscientious objector, and was granted exemption, conditional upon performing Work of National Importance, specifically, in his case, working in a farm.

In conformity with his absolutist principles, Wilson appealed to the Middlesex County Appeal Tribunal, but so also did the Military Representative, a statutory party to all Military Service Tribunal hearings. The Appeal Tribunal, in January 1917, dismissed Wilson’s appeal, which dismissal would, on its own, have left him with his conditional exemption, but the Appeal Tribunal allowed the Military Representative’s cross-appeal, which stripped him of any exemption whatsoever, determining that he was not a conscientious objector at all.

We have no detail on the next stage, but we know that the procedure would have been that Wilson was sent a notice to report to his allocated unit, the Royal Fusiliers, for training. which Wilson would have ignored. His failure to report would have been notified to the local civilian police, resulting in a constable arresting him and bringing him before Acton Magistrates’ Court, which would have fined him, probably 40/-, and handed him over to a waiting military escort. The escort would have taken him to the depot at Hounslow, where he had originally been directed to report. There he would have received a formal order, very likely to put on a uniform, which he would have refused to obey, resulting in a formal charge of disobeying the lawful command of a superior officer and being detained in the guard room for court-martial.

It is known that Eli Marsden Wilson was court-martialled at Hounslow, on the 21st February 1917, and sentenced to 112 days imprisonment. He was taken to Wormwood Scrubs to serve his sentence, where he was routinely brought before the Central Tribunal, sitting at the prison, on the 12th April 1917, where he was acknowledged to be a conscientious objector (CO) after all, and offered admission to the Home Office Scheme, whereby CO prisoners could be released on indefinite licence, subject to performing civilian work under civilian control at specially created work centres.

Again, as an absolutist, Wilson refused the offer, meaning that he continued his sentence, and at the end was automatically returned to the Army. Back at Hounslow, Wilson was given another order, which he again refused to obey, resulting in a second court-martial on the 12th June 1917, and a sentence of two years imprisonment with hard labour. It is not clear whether Wilson began this second sentence at Wormwood Scrubs, but it is known that he ended up at Pentonville Prison. He was eventually released in April 1919. As conscription was now being wound down, following the Armistice, Wilson was not returned to the Army, who would have eventually tidied up their paperwork by sending him a formal discharge from the Army, probably in 1920.

Because of his stance as a conscientious objector, Wilson was not seen in a good light by his extended family back in Ossett, many of whom fought in WW1, but made no such moral distinction. In all, during WW1 there were more than 16,000 recorded British conscientious objectors; 6,312 were arrested; 5,970 were court-martialled and sent to prison, where they endured privations both mental and physical (819 spent over two years in prison, including Eli Marsden Wilson). At least 73 COs died because of the harsh treatment they received; a number suffered long-term physical or mental illness. 1,330 ‘absolutists’ like Wilson refused to do any kind of alternative war work, but never won exemption for this principled stand.

Some agreed to join the Home Office Scheme, which allowed COs out of prison to to take up places at Work Camps where they carried out menial tasks such as farm work, construction and forestry. Some of the COs found this kind of work not much to their liking, so changed their minds and went back to prison. A few ‘absolutists’ volunteered for the Home Office Scheme, but were kept separate from the other COs. And after the Armistice? No one was in a hurry to release the COs; certainly not until the surviving soldiers were brought back from the front, which took months.

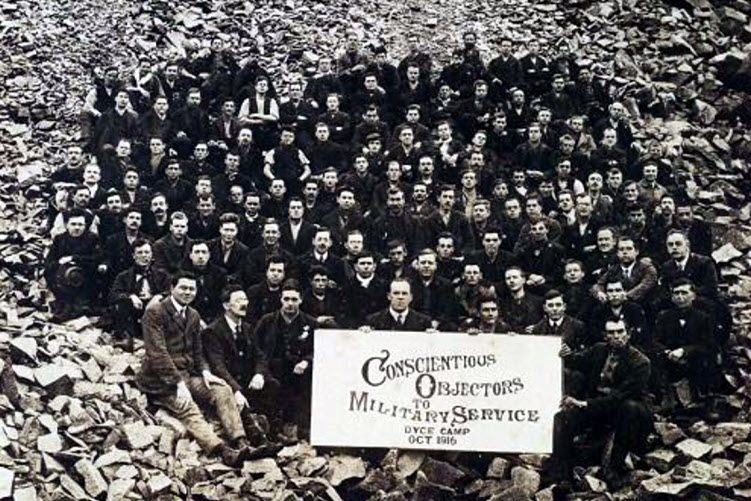

Above: Conscientious Objectors at Dyce Work Camp, near Aberdeen. Opened in late 1916, it was was made up of 250 conscientious objectors. As an alternative to prison, their punishment was to break rocks in a granite quarry. Living conditions at the camp were basic and many of the men were unused to hard labour. One of the conscientious objectors, Walter Roberts from near Stockport, died of pneumonia, and Dyce Camp came to wider attention. The other men stepped up a letter writing campaign complaining about the conditions. There were visits to the camp by a Home Office committee and by future Labour prime minister Ramsay McDonald. On the 19th of October, following a debate in Parliament, it was announced that Dyce camp would close. Barely two months after their arrival, the conscientious objectors were dispersed to prisons across Britain to complete their sentences.

Some COs went on hunger strike in protest at their continued detention: 130 were forcibly fed through tubes (as suffragettes had been), so forcibly that many were injured by the treatment and had to be temporarily released. Others went on work strikes and were brutally punished for it. In May 1919 the longest-serving prisoners began to be released; the last CO left prison in August of 1919. Many found that no one wanted to employ them. Those who hadn’t done alternative or non-combatant service were deprived of their votes for five years, although this wasn’t always strictly enforced.

A surprising number of conscientious objectors subsequently went on to become Labour MPs after WW1. Herbert Morrison, Labour MP for South Hackney and later Lewisham, became the Home Secretary and a member of Churchill’s War Cabinet in WWII, but was a conscientious objector in WWI. Fenner Brockway, a prominent conscientious objector during WW1, became the Labour MP for Slough in 1950, serving until 1964. Another CO, Ness Edwards was the Labour MP for Caerphilly between 1939 and 1968.

After being released from prison, Eli Marsden Wilson slowly began to rebuild his career and in 1922, HRH Princess Mary Louise commissioned him to produce an etching for Queen Mary’s dolls house, which can be seen today at Windsor Castle. Clearly, his stance as a pacifist during WW1 had been forgiven, by the Royals at least.