This is the story of Reginald Earnshaw known to family and friends as Reggie who died at sea in the service of his country on July 6th 1941 at the age of 14 years and 152 days. On February 5th 2010, almost 65 years after the end of the war, he was officially declared the youngest known British service casualty of WWII by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. That day would have been Reggie’s 83rd birthday.

Since that time much has been written about Reginald Earnshaw but until now little has been told of the story of his short life and the lives of his mother and grandparents who helped to make him what he was.

Reggie lived at The Millers Arms, Healey, Ossett from shortly after his birth on February 5th 1927 until shortly before his fifth birthday.

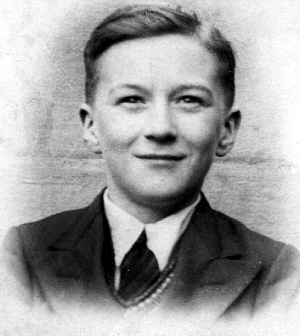

Reggie pictured as a schoolboy shortly before joining the Merchant Navy

Reggie’s early years in Ossett with his mother and grandfather.

Reginald Earnshaw was born in Moorlands Maternity Home, Dewsbury on February 5th 1927, the only son of 21 years old single mother Dorothy Earnshaw who was the only child of Wilson Earnshaw and Lily Sutcliffe who married in late 1893. Dorothy took her newly born son to her home at The Millers Arms, Healey, Ossett where her father, Wilson Earnshaw, by then a widower, had been the licensee since November 2nd 1914. In the years 1914-1919 Wilson would have seen many Healey families lose their loved ones in WWI. He too had lost the love of his life, his wife Lily aged 47 years, with flu, at the time of the Spanish influenza pandemic in late 1918. He knew of the pain of losing that irreplaceable love. Dorothy, aged just 13 years at the time of her mother’s death, was his only child from some 25 years of marriage and Reggie was his only grandson. So it was that Reggie came to live in Ossett.

Reggie’s grandfather Wilson Earnshaw was born in Morley on September 20th 1867 and in the absence of Reggie’s birth father Wilson Earnshaw would become an important influence in the very earliest years of Reggie’s young life.

Wilson’s father Joseph had married Elizabeth Wilson in 1863 and in 1871 the couple lived in Dewsbury with their two children Louisa (born 1864) and Wilson (born 1867). Elizabeth’s brother, Harry, was a lodger and working as a mason. Sadly, Elizabeth, died in summer 1874, perhaps in childbirth, aged 30 years. By 1881 Wilson and Louisa were living in Morley with their aunt Sarah Scholes (nee Earnshaw) and her husband, William, who was a stone mason. Ten years later in 1891 both Louisa, then married, and Wilson were still living with their aunt and uncle. Wilson was employed as a stone mason.

In summer 1893 Wilson Earnshaw played his first game for Yorkshire Cricket Club for whom he kept wicket and played as a right handed batsman. The same year Wilson, 26 years of age, married Dewsbury lass Lily Sutcliffe aged 21 years. By 1896 Wilson had played six games for Yorkshire making 44 runs and taking eight wickets and in the late 1890’s the couple moved to live on Scotchman Lane, Morley. By 1901 they had moved to Accrington where Wilson worked as a stone mason. Their only child, Dorothy, was born there on September 1st 1905 and a new career was beckoning.

From 1906 to 1932 Wilson Earnshaw (pictured opposite about 1900-1905) earned his living as the licensee of Public Houses. His first was The Travellers’ Rest, Chickenley until 1912 when he took over The Royal Oak, Albion Street Batley until 1914. His third and final pub was The Millers’ Arm at Healey, Ossett which he ran between November 2nd 1914 and October 10th 1932, by which time Wilson Earnshaw was 65 years of age. He died in Low Town Pudsey on November 24th 1941 aged 74 years.

Dorothy Earnshaw’s marriage and the move from Ossett to Edinburgh via Dewsbury.

By the time of her father’s death in 1941 Dorothy had been married for ten years, had two children from the marriage and was living in Edinburgh. The country was at war and she had also lost her only son Reggie who tragically died at sea on July 6th 1941, just four months before his grandfather passed away.

Dorothy Earnshaw was no ordinary woman. Strong willed, determined and not one to suffer fools gladly were all the best of attributes for a young woman who played a major role in helping to run The Miller’s Arms with her widowed father. There was however much more to Dorothy for she was also a gifted pianist, a keen and knowledgeable musician. At birth Reggie was given the second name, Hamilton, in honour of Sir Herbert Hamilton Harty for whom Dorothy had a great admiration. Irish born Hamilton Harty was a gifted organist, piano accompanist, composer and conductor of the Halle and the London Symphony Orchestras. He too died in 1941. So when Reggie is spoken of we should also remember his full name, Reginald Hamilton Earnshaw for it tells us much more of him and his mother Dorothy. A spirited woman ahead of her time.

By the end of 1931 Dorothy Earnshaw had spent virtually the whole of her life living in public houses run by her father, Wilson Earnshaw. Since February 1927 when Reggie was born and brought home to The Millers Arms by Dorothy she also had the warmth and comfort of his company. However it wasn’t quite enough and Dorothy had met and fallen in love with Dewsbury born Eric Shires.

Above: Dorothy (nee Earnshaw) and Eric Shires.

At 11 a.m. on Wednesday August 5th 1931 at Christ Church, South Ossett 25 years old Dorothy Earnshaw of The Millers Arms married 26 years old Earlsheaton born Eric Shires, a wool blender, of 22, Wakefield Road, Dewsbury . Mr. W Earnshaw of The Millers Arms Ossett proudly issued invitations to family and friends requesting the pleasure of their company at the marriage of his daughter, Dorothy. The invitations bore the address of The Millers Arms.

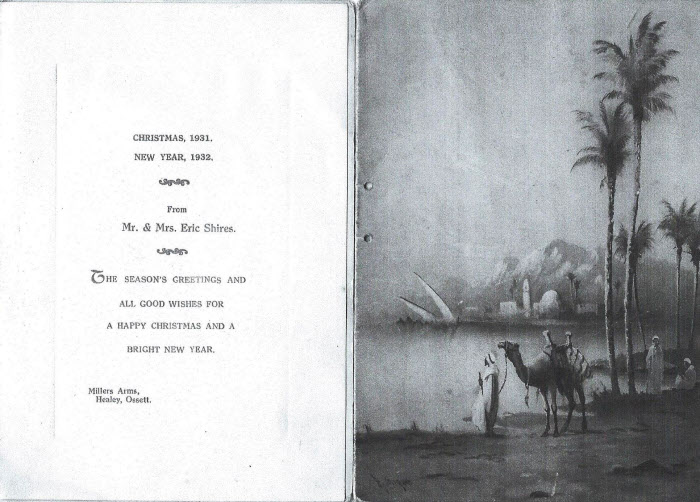

At Christmas 1931 Dorothy and Eric sent family and friends Christmas cards bearing their names and the address of The Millers Arms suggesting that the newly wed lived there with Reggie and Wilson until at least that time. Reggie would have his fifth Christmas there. By spring 1932 the couple had moved with Reggie to live at 11, Mill Street West, Dewsbury where two daughters were born to Dorothy and Eric Shires; Pauline in spring 1932 and Neva in late 1934.

Above: Christmas 1931 / New Year 1932 Card from Dorothy & Eric Shires bearing their home address. The Millers Arms, Healey, Ossett.

In 1938 the Dewsbury woollen mill in which Eric Shires worked went into administration and he became unemployed. With a wife and three children to support it was imperative that he find work but local work of that kind was at a premium. He cast his net wider and found the opportunity in far away Edinburgh.

Reggie was 12 years of age when he was confirmed at Dewsbury All Saints Parish Church on March 23rd 1939. The same year, Eric may have left Dewsbury for Edinburgh a little earlier than the rest of his family who joined him there in summer 1939; the family lived in the Granton area of Edinburgh. Pre war Granton was the key base in Scotland of the Northern Lighthouse Board with their boats taking lighthouse keepers and their supplies to and from lighthouses around the coast of Scotland. What an adventure it all must have been for young Reggie.

1941 Reggie leaves school, joins the Merchant Navy and loses his life.

Reggie left his school, Bellevue, now Drummond Community High School, Edinburgh at the statutory leaving age of 14 years. It was 1941. The country was at war and there was much talk of feats of daring do which fired the imagination of many young boys. Reggie was one of them and he determined to help the war effort whilst seeking excitement and adventure. At that time he lived within walking distance of Leith Docks and he joined the Merchant Navy there in February 1941. He claimed that he was born on February 5th 1926 and that he was 15 years of age. He lied about his age so that he wouldn’t be disappointed but the truth was that he was born exactly one year later and he was only 14 years of age.

Reggie’s family tell that there was never a suggestion that he had run away and gone to sea but rather that he was proud of what he had done and rushed home to tell his mother. She knew her son well and that he was bright, active and full of life. Like his mother he was a free spirit whose enthusiasm was to be encouraged not stifled.

The merchant ships of the British Merchant Navy kept the United Kingdom supplied with raw materials, arms, ammunition, fuel, food and all of the necessities of a nation at war throughout World War II literally enabling the country to defend itself. In doing this they sustained a considerably greater casualty rate than almost every branch of the armed services and suffered great hardship. It was known that service aboard would involve risk.

Reggie served aboard as a cabin boy for a few months and on July 5th 1941 the merchant cargo ship North Devon left Ipswich in ballast for the Tyne and joined up with the 82 ship coastal convoy EC-42. On the evening of July 5th at 21.30 (GMT) the convoy was attacked by a number of German bombers. Four bombs which were all near misses exploded close by North Devon fracturing the ship’s main steam lines causing the ship to stop dead in the water. At 00.30 (GMT) on July 6th another enemy aircraft attacked the North Devon with machine gun fire while releasing another three bombs which again were all near misses.

An hour later the HM Trawler “Neil Mackay” arrived to offer assistance and towed the ship towards the Humber. Mean while it was discovered that six of the crew including young Reginald, whose body was found in the Engineers’ alleyway had been killed, while others would die from their injuries, all scalded to death after the main steam line had burst in the first attack. The following day

the ship docked at Immingham and the bodies of two crew members were taken ashore, with one other being found the following day and brought ashore. i

Above: The SS North Devon. Reggie died when the Germans bombed the ship in 1941.

Reggie’s family were to be devastated by the news of his death and haunted by the memory of the return of his body to his home where it was to rest awhile in readiness for the funeral. True to her only son until the very end Dorothy took charge of the arrangements for Reggie’s funeral service and his burial. His mother Dorothy, stepfather Eric and their two daughters, Pauline and Neva, took what comfort they could from the service and the card of condolence from the King and Queen; it bore the words R.Earnshaw, SS N. Devon.

The funeral service was the very first to be held at the newly built St. David’s Episcopal Church, Pilton and officiated by Reverend George Wilson. Following the service Reginald Earnshaw was buried in an unmarked grave in Section P. Grave 440 at Edinburgh (Comely Bank) Cemetery. It was comfort enough for the family to know that Reggie was resting nearby. For them this was to be an end. In modern parlance it was closure. Until……

Reginald Earnshaw. The circumstances of his death and memorials to his name.

Standing on the south side of the gardens of Trinity Square, London, close to the Tower of London is the Tower Hill Memorial. It commemorates the men of the Merchant Navy and Fishing Fleets who have no grave but the sea. More than 50,700 Commonwealth merchant seamen lost their lives in the two world wars. The Tower Hill Memorial commemorates more than 35,800 casualties who have no known grave. Reggie’s name is engraved there it then being believed that he had no grave but the sea.

Just a month and a day after Viscount Lascelles, later to become the 6th Earl of Harewood, unveiled the Ossett War Memorial the Tower Hill Memorial was unveiled on 12 December 1928, by his mother in law Queen Mary. The Tower Hill Memorial was later extended to commemorate the men of the Merchant Navy who lost their lives during the Second World War. It was unveiled by Queen Elizabeth II on 5 November 1955.

This was the year that Dorothy’s daughter, Pauline, married and it was also around this time that Dorothy and Eric Shires left their home at 3, Wardie Park, Edinburgh to return to Yorkshire to live at West Park, Harrogate. Eric Shires died at Great Clowes Street, Salford on September 29th 1969 aged 64 years. Dorothy moved to Epworth, Lincolnshire to live near her daughter Pauline Harvey (nee Shires)and she died there in 1987 aged 81 years. Her ashes are interred at the parish church. Dorothy Shires nee Earnshaw.

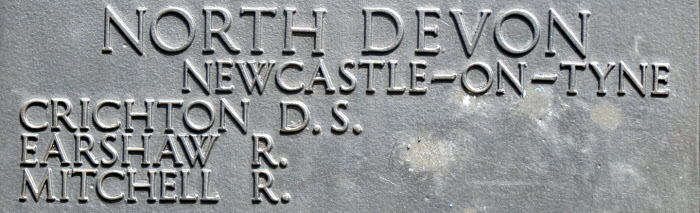

Reginald Earnshaw is remembered (albeit as Earshaw) on Panel 74 of the Tower Hill Memorial as one of those men and women lost in WWII who have no grave except the sea.ii It is supposed that the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) knew of Reggie’s death but in the absence of any information about his burial place it was assumed that he had no grave except the sea. The CWGC search for the facts may have come to nought because Reggie’s name was Earnshaw whilst his mother’s married name was Shires and/or because the family couldn’t be traced because they had moved house shortly after WWII.

Above: Reggie’s name on the Tower Hill Memorial (Panel 74) alongside two of his shipmates Douglas Crichton and Reginald Mitchell also died at sea on the S.S. North Devon on July 6th 1941. Douglas Crichton was cremated at Warriston Crematorium, Edinburgh and Reginald Mitchell was buried at Piershill Cemetery Edinburgh.

In 2005, fifty years after this Panel would be seen for the first time, a man called Alfred (Alf) Tubb, then 82 years young, had a moment in his life which would change history. Mr Tubb was also serving on the North Devon on that fateful evening and he knew something that the Commonwealth War Graves Commission did not know. Reginald Earnshaw‘s body was brought ashore and so, somewhere, Reggie had a grave other than the sea.

Alf Tubb, served alongside Reginald as a DEMS machine gunner and tried in vain to save his friend. Alf, who was only 18 years of age while aboard the North Devon, began his search for Reggie’s resting place in 2005 reaching out to others to help him in his quest. In June 2009 in an interview with Deadline Scotlandiii, Alf said:-

“I remembered him partially because he was so young. I don’t think he enjoyed the sea life too much – I remember him saying that he was looking forward to going back home to see his mum. He was a slim, cheerful lad, with a shock of blonde hair – almost white, in fact.

I could tell that we were about to be attacked, so I went on watch ten minutes early to get my eyes used to the darkness. We were bombed twice – I know I shot down one of them but it turned into absolute chaos and I was blown off my post. Men were diving into the sea, and the ship was listing badly, I thought we might sink.

Somebody told me that Reggie was still in his cabin above the engine, and I went to try and get him out, but the steam was just too hot. I’d heard that during the first world war troops used to pee on towels, and put it over their faces to protect against gas. I tried that with the steam but it didn’t help at all – you just couldn’t breathe because of the heat.”

He was a cheerful lad, and we used to chat in the saloon of the ship. After we were attacked, my last memory of Reggie is seeing him carried off the vessel when we docked at Immingham – he’d been cooked by boiling steam. During the attack he was trapped in his cabin, I tried desperately to get to him but the steam was like a scalding wall.

That image has stayed with me forever, so the most important thing to me now is that he gets a fitting headstone. I am glad that after all these years the sacrifice of such a young man – my pal – will be properly marked.

I knew he had to have a grave somewhere because I saw his body being carried off the ship – but when I found his resting place in Edinburgh there was just a bare patch of earth.”

Alf reached out and discovered several men well versed in mercantile research. Alf’s quest moved on apace with the knowledge, assistance, determination and dogged persistence of the remarkable Billy McGee, Roger Griffiths, Hugh MacLean, Ray Buck and Bill Watt.

They proved that Reggie had been brought from the S.S. “North Devon” to Immingham and it was clear therefore that he had a grave other than the sea. They then discovered that Reggie was buried in an unmarked grave in Edinburgh’s Comely Bank Cemetery. A temporary cross bearing his details was added and all documents were forwarded to the CWGC. On March 20th 2008 the combined effort and findings were officially accepted by the CWGC 4.

On Monday July 6th 2009, in a ceremony 68 years to the day after Reggie’s death an official CWGC headstone was finally mounted on Reginald’s grave in Edinburgh (Comely Bank) Cemetery (see opposite).

On February 5th 2010, almost 65 years after the end of the war, Reggie was officially declared the youngest known British service casualty of WWII by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. That day would have been Reggie’s 83rd birthday.

Sadly, Reggie’s family were not able to attend the ceremony on July 6th 2009 when the CWGC mounted a headstone on Reggie’s grave at Comely Bank Edinburgh. Until later in 2009 the family was oblivious to the search by Alf Tubb and the researchers who were assisting him and they, and the CWGC, were unaware of the existence of Reggie’s descendants.

Once the family became aware of the campaign to properly remember Reggie, his sister, Pauline Harvey (nee Shires) was able to provide the CWGC with information to satisfy them as to Reggie’ s credentials. Pauline and her great niece, Jenny, were able to attend the ceremony and lay flowers on February 5th 2010 when Reggie, who spent 12 years of his young life in Ossett and Dewsbury, was officially declared the youngest known British casualty of WWII.

On that day Pauline Harvey, who was only nine years of age when Reggie was killed in July 1941, met relatives of Douglas Crichton and Reg Mitchell, who were also killed in the attack on S.S. North Devon. Pauline had this to say about that fateful day in 1941 and expressed her heartful thanks to those who had made this journey possible:-

“Reggie’s death at such a young age and after just a few months at sea came as a great shock to the whole family. I am immensely grateful to so many people who helped research my brother’s forgotten story, and to the War Graves Commission for providing his grave with a headstone.”

The ceremony on 5th February 2010, a day which would have been Reggie’s 83rd birthday, might have been the end of this compelling story to ensure that Reginald Earnshaw’s rightful place in history was secured.

Until . . . .

Reginald Earnshaw Memorial Window

Reggie’s July 1941 funeral service was the very first to be held at the newly built St. David’s Episcopal Church, Pilton, Edinburgh. 70 years later so moved was Reggie’s local parish church and parishioners, to his story and the deaths of so many other young boys lost at sea, a memorial stained glass window was commissioned and installed in the church in 2011.

The church had followed closely the development of Reggie’s story and it was determined to honour his memory as well as the memory of over 500 boys aged 16 and under who died in service with the Merchant Navy in WWII.

On May 7th 2012 a memorial service took place at the church to unveil the window inscribed with a picture depicting Reggie and the words:

“To the glory of God and in loving memory of Reginald Earnshaw who died aged 14 the youngest known service casualty of the second world war. Sacred to the memory of over 500 boys of the Merchant Navy aged 16 and under who died in the service of their country during world war two.”

Above: St. David’s Episcopal Church Memorial Window depicting Reginald Earnshaw.

The Imperial War Museum (IWM) classify the Reginald Earnshaw Window as a War Memorial known as The R. Earnshaw Memorialv. It is described as a stained glass window, depicting a merchant ship and a cabin boy, with inscription on the glass.

The Inscription includes the following:- For Their Tomorrow We Gave Our Today: Lest we Forget: To The Glory of God And In Loving Memory Of Reginald Earnshaw Who Died Age 14 The Youngest Known Service Casualty Of The Second World War.

And so Reginald Earnshaw will end his journey where it began; in Ossett. For Remembrance Sunday 10th November 2019 the name of Reginald Earnshaw will be engraved on one of the granite memorial stones laid around the base of the Grade II Listed Ossett War Memorial in the Market Place.

From then and forever Reginald Earnshaw, the youngest known British service casualty of WWII will be known as one of The Ossett Fallen; 409 men and women of Ossett who lost their lives in the service of their country in WWI or WWII.

Reginald Earnshaw has returned to his first home.

We are much indebted to Reggie’s sister Pauline Harvey, her daughters Louise and Frances, and their cousin Fiona, for sharing their dearest memories and family history which has enabled us to enrich this biography. Our hope is that the biography and Reggie’s place with The Ossett Fallen will act as a touchstone for their children and their children’s children as they remember Reggie’s sacrifice. He gave his tomorrow for our today. Lest We Forget

We are also grateful to Andrea Hartley for bringing Reggie to our attention.

Postscript: The death and destruction of war are the greatest of human tragedies, and dying young simply, poignantly compounds those tragedies. For every Reginald Hamilton Earnshaw or others who remain nameless, there is a story of family, lost life, and unrealized potential. Such is the price of war.6

Awarded to Reginald at his former home, The Millers Arms, Ossett, 28 September 2019

Cabin Boy, Reginald (Reggie) Earnshaw aged 14 years

Merchant Navy, S.S. North Devon (Newcastle-On-Tyne)

Reginald Earnshaw was 14 years and 152 days old when he lost his life aboard his merchant ship during an attack by the enemy off the East Coast of Yorkshire on 6th July 1941. Almost 69 years later on February 5th 2010, the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) officially declared Reginald Earnshaw the youngest known British service casualty of WWII. That day would have been his 83rd birthday.

On 28th September 2019 Reginald made more history when Ossett’s first Blue Plaque, bearing his name, was unveiled at his Ossett home. In November 2019 his engraved name was unveiled by Service Cadets at the Ossett Memorial in the Market Place where he joined his brothers and sisters in arms; The Ossett Fallen.

Reginald’s other honours

In addition to his Blue Plaque and the engraving of his name at the Ossett War Memorial Reginald Earnshaw was remembered by the CWGC at the Tower Hill Memorial, London. Tower Hill was erected in 1955 to commemorate the men of the Merchant Navy and Fishing Fleets who have no grave but the sea. But, unknown to the CWGC, Reggie was brought ashore that fateful day and he did have a grave; at Comely Bank Cemetery, Edinburgh.

Thanks to years of persistence and determination by a Merchant Navy colleague, octogenarian, Alf Tubbs, who was aboard the same bombed ship and the efforts of several mercantile researchers , in 2008 their combined efforts and findings were officially accepted by the CWGC.

On July 6th 2009, in a ceremony 68 years to the day after Reggie’s death an official CWGC headstone was mounted on Reggie’s Edinburgh grave. Reggie’s 1941 funeral service was the very first to be held at St. David’s Episcopal Church, Pilton, Edinburgh. In May 2012 a memorial service was held there to unveil a window inscribed with a picture depicting Reggie to honour his memory as well as the memory of over 500 boys aged 16 and under who died in service with the Merchant Navy in WWII.

Reggie Earnshaw’s legacy continues and the CWGC (Scotland N&E) are now to use information about Reggie on their website and in their tours and presentations to adults and children. Reggie Earnshaw, made in Yorkshire, died in Yorkshire, buried in Scotland. He was a man before his time.

Reginald Hamilton Earnshaw

Ossett’s first Blue Plaque was awarded to the youngest serviceman who died in WWII.

29th September 2019. The day of the unveiling of Ossett’s first Blue Plaque at Reggie’s first home, The Miller’s Arms Public House now known as Brewer’s Pride at Low Road, Healey, Ossett. The weather was unkind to us but approximately 100 persons attended the ceremony which was covered by ITV television and the Yorkshire Post newspaper.

Ossett Brewery and several individuals sponsored the Blue Plaque at the Brewers Pride. Reggie’s sister, Pauline Harvey, her two daughters, Louise and Frances, and a cousin Fiona Nicklin and her partner, Alan, were present at the unveiling ceremony. In recognition of Reggie’s Scottish connection and his Edinburgh burial place a Piper, David Holdsworth played in the procession.

Following brief introductions Ossett born, 98 years old John Hirst, who also joined the Merchant Navy in 1941, unveiled the Blue Plaque to honour his Merchant Navy colleague. The Royal British Legion Branch Chairman, Malcolm Patterson and Ossett Parade Marshall,

Peter Waters, led the Act of Remembrance. Bugle calls for the Last Post and Reveille were played by Charlie Welch, courtesy of the Horbury Victoria Band. Pauline Harvey laid a Merchant Navy Wreath for her brother Reggie following which the Piper played to conclude proceedings.

Thanks are due to Andrea Hartley for bringing Reginald to our attention.

There follows the Tribute to Reginald and the Order of Ceremony to unveil Ossett’s first Blue Plaque in his honour. The ceremony was held at The Brewers Pride (formerly The Millers Arms) 11am on 28th September 2019.

Sources

i Billy McGee WW2 Talk Forum “The War at Sea”

iv Commonwealth War Graves Commission

v Imperial War Museum War Memorials Register