Gilbert Frudd was born in Thornhill on the 16th June 1895, one of six children, and the youngest son born to coal miner George Williamson Frudd and Mary Firth who married in spring 1887. He was baptised at Thornhill Chapel on the 3rd September 1895. By 1901, George and Mary were living with their family, all born in Thornhill, in Conisbrough and by 1911 they had returned to Thornhill. By this time Gilbert was 15 years of age and, like his father and an elder brother, he was already a coal miner and living with his parents and four of his siblings at Low Lane, Middlestown.

Gilbert Frudd served in WW1 in the 12th Battalion, Kings Own Yorkshire Light Infantry (KOYLI) as Private 12/1783 and was awarded the British and Victory Medals indicating that he served overseas in a theatre of war but not before 1st January 1916. The 12th (Service) Battalion (Miners)(Pioneers) KOYLI was formed in Leeds on the 5th September 1914 by the West Yorkshire Coalowners’ Association and moved to Farnley Park (Otley). In May 1915 the battalion moved to Burton Leonard (Ripon) and was attached as a Pioneer Battalion to 31st Division. It moved to Fovant in October 1915 and in December 1915 it moved to Egypt. The battalion went on to France in March 1916. and between 1 July and 30 November 1917, it was attached to Fifth Army Troops for work on light railways.

Gilbert was de-mobbed on 5th April 1919 and, as was the usual practice, he was placed in “Z” Reserve in the event that the Armistice didn’t hold. It seems likely that Gilbert moved to Ossett after 1911, perhaps after his war service, and in the summer of 1919, he married Susan Westerman of Audrey Street Ossett and the couple had one child, Mary, born in spring 1920. Sadly Susan Frudd, nee Westerman, died aged only 27 years in 1923.

In 1930, Gilbert, a widower and by this time 34 years of age married Lottie Pickersgill, a spinster aged 39 years, at South Ossett Christ Church on the 7th June 1930. Gilbert’s address was his family home at 6, Audrey Street, Ossett and Lottie lived at 6, Fawcett’s Buildings, off Manor Road, Ossett.

In 1939 Gilbert, a labourer undertaking heavy work, and Lottie were living with Gilbert’s daughter from his first marriage, Mary, and one other, at 6, Audrey Street, Ossett. Gilbert Frudd was 45 years of age when he died in service in WW2 and may be the oldest Ossett man to die in service in WW2. Gilbert was a second cousin (once removed) to James Frudd who died in WW1 aged 50 years. James was the oldest Ossett man to die in service in that War.

The Lancastria was guided into the sea lanes of the Loire estuary, and anchored some 10 miles off St Nazaire at about 06.00 hours on Monday, 17 June 1940. It was a beautiful misty summer morning.

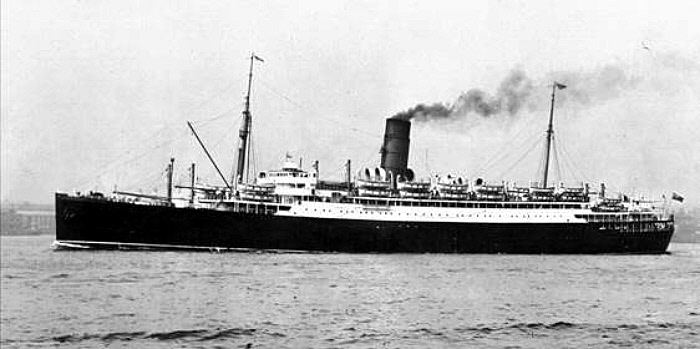

Above: HMT “Lancastria” which was launched on the Clyde in 1922, originally as the “Tyrrhenia.” She was a big ship at 16,243 tons, and 578 feet long. More significantly, she was actually fitted to carry only 2,200 passengers.

Almost immediately, exhausted troops and some civilians began to arrive and were given little tickets, like bus tickets, with their cabin and deck number. Some were given spaces in the vast holds of the ship, where they laid down to rest and were asleep in just a few minutes. Throughout the morning troops arrived and seemed to fill every available space. Some had their first hot meal in weeks; some remained on deck watching still more people come aboard. There were units from the Army and RAF as well as civilians – men, women and young children.

At about 13.00 hours the red alert sounded and a dive bomber was seen to attack the “Oronsay” which was some distance off. The bomber scored a direct hit on the bridge area, but it did not render the ship unseaworthy. Those on the deck of the Lancastria feared the worst: the enemy was sure to return. By this time the ship had taken some 6,000 people on board and more kept coming. At around 15.00 hours Captain Sharp decided that enough was enough, but that to sail straight away would court disaster – he would rather wait for an escort.

At about 15.50 hours the enemy returned and the ship’s ARP alarm was sounded. A Junkers JU 88, piloted by Peter Stahl flew over the Lancastria and dropped four bombs, all of which hit the Lancastria with fatal consequences. Captain Sharp claims in his report that one bomb went down the funnel, and the others hit hatches four, three and two. The funnel bomb didn’t actually fall down the funnel; it fell very, very close to the funnel, but nonetheless, the ship couldn’t have been hit in any worse places.

Above: Junkers JU88 bomber like the one that bombed and sank HMT “Lancastria” on the 17th June 1940.

The hatch covers were shattered and splintered and allowed the bombs deep into the ship. Hundreds would have been killed immediately, while others would have been trapped, beyond hope, behind wreckage. Of the RAF personnel aboard, from 73 Squadron and 98 Squadron, very few survived. In his report, Captain Sharp concludes that each of the bombs which struck the ship passed through the upper deck and hatches, bursting inside the ship and blowing holes in her sides.

The bomb that burst through number three hatch, actually hit the oil tank, and once the oil tank was burst it spilled hundreds of tons of the fuel oil, that should have been taken off at Liverpool into the sea around the stricken ship. The ship rolled onto her port side, down by the bow. Those who could, took to the water to try and swim though the black cloud of oil that here and there showed licks of flame.

Non-swimmers took to the water with whatever seemed to be able to keep them afloat. Some lifeboats were lowered but, on many, the davits could not be released because of the angle of the ship. Those still on board what was now an upturned hull watched as the enemy returned to strafe both those struggling for life on the hull and those in the sea. They sang in defiance at the tops of their voices “Roll out the Barrel” and “There’ll always be an England.” The ship’s siren wailed and by 16.10 hours, in just 20 minutes, the Lancastria slipped beneath the waves.

Then there was the silence, a silence louder than the clamour of exploding bombs and guns. So ended the life of a beautiful ship and the lives of thousands of men, women and children. No one will ever know the exact number who died that day, some say there were as many as 9,000 on board by the time the Lancastria was bombed, others estimate 7,000. All we do know is that around 6,000 were on board by 13.00 hours, and that many more arrived after that. Only 2,447 arrived home.

The rescue began with all kinds of vessels, from small fishing boats to destroyers of the Royal Navy, picking up survivors, more like oily flotsam than people. The bodies of those who died that day were washed up along the French coast during the coming months and were given Christian burials by the French people, who bravely ignored the German presence and cared for the victims as their own.

However, while in England most people were unaware of the tragedy, those living around the coast where Lancastria had sunk could not get away from it. Bodies were washed ashore from Piria, right down to the Île de Ré, just off La Rochelle, probably about three hundred kilometres of coastline. The first bodies came ashore on the 28th June 1940, and they kept coming all summer. The bodies were then taken away and buried in either local cemeteries or makeshift cemeteries and largely without coffins because they didn’t have the wood to make them.

A couple of local observations – Michel Lugez: “The bodies did not reach the shore immediately after the ship sank, but by July the bodies came ashore in large numbers. Here in Pornichet for example, there were two or three at each tide. At the Ponte du Bec there were others. At Sainte-Marguerite all along the coast there were corpses that were given back by the sea. At each tide, there were corpses being washed up on the beach.”

At the end of summer, the bodies stopped, and Charles Merlet writes: “We were walking along the coast on December 2nd. That’s when we noticed that there were bones. More bones and lots of military clothing, and in these clothes that had really deteriorated and were damaged we collected the wallets of these poor men who’d drowned, to identify them, and then the many bones; we never collected them, it was not possible. There were too many, all over3.”

Churchill immediately hid the news from the public. In 1940, after Dunkirk, to reveal the truth would have been too damaging for civilian morale. He said, “The newspapers have got quite enough disaster for today, at least.” Since that time the disaster has never been recognised for what it was: the greatest maritime disaster in Britain’s history. More people were killed on the Lancastria than on the Titanic and Lusitania put together.

Although some photographs appeared in the American press late in the summer of 1940, and were then published in the UK, the full story of the Lancastria never came out. The official details of the disaster are still not available to the general public and will not be released until 2040, 100 years after the tragic incident.

Above: The SS Lancastria sinking after being being bombed by German aeroplanes on the 17th June 1940 during the evacuation of civilians and military personnel from St. Nazaire, France.

The “Ossett Observer” carried this obituary for Private Frudd.1

“Body Found On French Coast – We announced some time ago that Mr. Gilbert Frudd, 6, Audrey Street, Ossett, who was serving with the Auxiliary Military Pioneer Corps, was missing, and that all efforts to trace him up to that time had been unsuccessful. Fears as to his safety were felt when a letter was received from his Army pal, a Nottingham man, stating that the last he saw of him was on board the troop ship Lancastria, which was struck by bombs from the air, and sunk off Brest on June 17th: “I saw nothing of Gilbert in the water,” he wrote. “Being a good swimmer, I managed to keep afloat until I was picked up.” Of the 5,300 on board, 2,800 were missing, and it is known that many of those thrown into the water lost their lives by machine gun fire. Mrs. Frudd has now received from the War Office that her husband’s body was washed ashore at St. Nazaire, France, and interred on July 5th in Clion Cemetery, France.

Mr. Frudd, who was 45 years of age was the youngest son of Mr. and Mrs George Wilkinson Frudd, of Thornhill, was a native of Thornhill Edge, but had lived in Ossett 21 years and was employed for 16 years at Roundwood Colliery. He served with KOYLI in the last war and was badly wounded and confined to a German prison for nine months. When the present was broke out he joined Ossett’s air raid precautions service as a stretcher bearer and in January last year, enlisted in the Pioneer Corps. He was sent out to France in March, and remained there until the evacuation of troops following the French capitulation. He met his death on his way home.

He was of a retiring disposition, and he was well-known and respected in the town. He leaves a widow and two daughters (one of whom has been serving with the Auxiliary Territorial Service since the outbreak of the war) to mourn his loss.”

Above: A plaque unveiled at Liverpool Pier Head in memory of those who lost their lives on HMT Lancastria in 1940.

Private Gilbert Frudd died on the 17th June 1940 aged 45 years and is buried in the Collective Grave 4 at Le Clion-sur-Merin Communal Cemetery, France. The village of Clion-sur-Mer is 44 kilometres west-south-west of Nantes and 4 kilometres east of the small town and fishing port of Pornic. The Communal Cemetery is on the western side of the village and the British graves are in the northern part of the Cemetery.2

References:

1. “Ossett Observer”, Saturday, December 7th 1940