Ashley Giggal was born on the 28th July 1910, the only son and youngest child of insurance agent and, latterly, shopkeeper, Nathan Giggal and his wife Mary Jane Lowther, who were married at the Central Baptist Church, Ossett on the 7th August 1899. Mary Jane was the daughter of grocer, George Lowther of Wesley Street, Ossett and Nathan was an insurance agent of Horbury Road, Ossett at the time of his marriage. Ashley and his two sisters were baptised at Ossett Green Congregational Church on 2nd October 1910.

By 1911, the couple were living at 29 Horbury Road, Ossett with their three children, and also with two daughters from Nathan’s first marriage, in the summer of 1891 to Ada Parr, who sadly died in early 1898 aged only 27 years.

Nathan Giggal of ‘Fairfield House’, Wesley Street, Ossett died on the 3rd August 1933, aged 70 years, and probate was granted to his widow Mary Jane Giggal. His effects were £1917 2s. In 1939, Ashley was living with his widowed mother, Mary Jane, born 17th November 1872, and his sister, Ada, born 18 January 1901, a manageress in a children’s ware shop at 37, Wesley Street, Ossett. Mary Jane Giggal died in 1947, aged 74 years whilst she was still living in Ossett. Ashley’s spinster sister Ada Giggal married Herbert Pickles in 1948 in the Ossett area.

By January 1929, Ashley was working for the Post Office, and qualified as a certified wireless operator, later joining Marconi Marine as a ship’s radio officer from about the age of 20 years. His last ship, before being transferred to the Royal Navy in 1940, was the tanker MV ‘Luxor’, which survived WW2. It is known that on the 24th September 1937 Ashley Giggal arrived by ship in Honolulu, Hawaii.

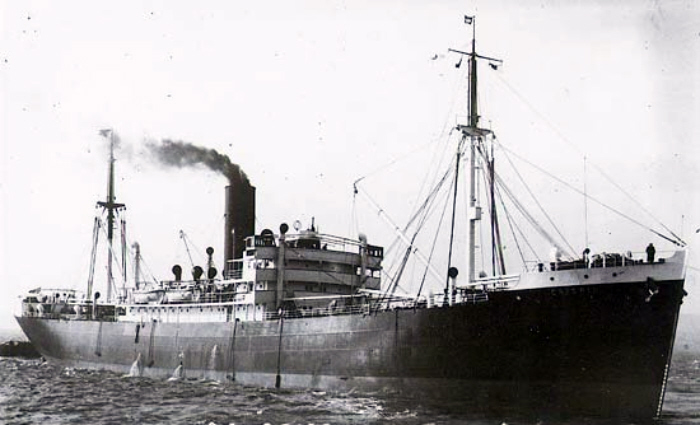

On his transfer to the Royal Navy, Giggal was the 1st Radio Officer on HMS ‘Crispin’, an armed merchant (OBV) ocean boarding vessel. Named after St. Crispin, the patron saint of shoemakers, the 5,051-ton S.S. Crispin was a cargo ship that was built in 1935 by Cammell Laird and Co. at Birkenhead, England. The ship was built for the Booth Steamship Company (also known as the Booth Line) and was based at Liverpool, England. Crispin was approximately 410 feet long and 55 feet wide and had a top speed of 13 knots. For roughly five years, Crispin was used by the Booth Line primarily on its route between England and Brazil, although the ship did make stops in the United States as well.

In August 1940, Crispin was acquired by the Royal Navy for use as an “ocean boarding vessel” during WW2. Ocean boarding vessels (OBVs) were merchant ships, which had guns added to them for the purpose of enforcing wartime naval blockades. Theoretically, they were to be used to board foreign vessels. In a secondary role, they would also be used as anti-aircraft ships to help protect convoys against German long-range bombers, such as the dreaded four-engine Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Condor. Crispin was armed with one 6-inch gun, one 4-inch gun, six 20-mm guns, and two .303-caliber Lewis machine guns. Fully equipped as an OBV, Crispin carried a rather large crew of 141 officers and men. The ship also was loaded with empty oil drums, which were to give it, in theory at least, added buoyancy in case she was torpedoed. Commissioned as HMS ‘Crispin’, the ship was assigned to escort merchant convoys that were headed across the Atlantic to Canada.

Once Crispin was commissioned, though, her real mission was disclosed to her crew by the ship’s captain, Commander B. Moloney. He told his crew that Crispin would act as a “Q-Ship”, or a decoy, which would trail a convoy looking like a helpless cargo ship in hopes of attracting German aircraft and surfaced submarines, thereby drawing the enemy away from the convoy. According to the captain, while at sea the Red Ensign of the British Merchant Navy would be flown, all guns would be hidden until needed, and then Crispin would open fire as soon as the enemy was sighted. In addition, the crew would not wear Royal Navy clothing while on the upper deck. Because of this, the captain warned the crew that if they were taken as prisoners of war, they would not be treated as such under the Geneva Convention, since they were not in uniform. Crispin would trail a convoy sailing from England to Canada, and then as soon as the ship neared its destination it would join an east-bound convoy headed back to England. Once reaching England, Crispin was to return to her base at Liverpool.

Q-Ships showed just how desperate the Royal Navy was in trying to deal with the dangers posed by U-boats and long-range bombers, which were taking a heavy toll of British merchant ships. Yet HMS ‘Crispin’ went out and tried to do her duty, even though at the time it was almost considered to be a suicide mission to use cargo ships as anti-aircraft and anti-submarine vessels.

The ship had just detached from the dispersed convoy OB-280 together with HMS ‘Arbutus’; the British armed yacht HMS ‘Philante’, and the British rescue ship ‘Copeland’ to join the convoy SC-20. For several months, Crispin escorted convoys that were sailing between England and Canada, and made no contact with the enemy, then, at 23:33 hours on the 3rd February 1941, HMS ‘Crispin’ was hit in the engine room by one torpedo from German U-Boat, U-107, north-northwest of Rockall. A total of 121 crewmen managed to abandon ship and were picked up by two other British escorts that were in the area. HMS ‘Crispin’ was abandoned and slowly sank the following day at position 56°52’N / 20°22’W. The commander, five officers and 14 ratings were lost. Eight survivors were picked up by the rescue ship and the remaining survivors by HMS ‘Harvester’ and landed at Liverpool.1

Crispin and her crew did the best they could with what they had. But cargo ships were never meant to be warships and the entire Q-Ship program was abandoned by the Royal Navy a few months later.

The U-107 went on to sink another 36 vessels, but was sunk on the 18th August 1944 in the Bay of Biscay south-west of St. Nazaire, in position 46°.46’N, 03°.49’W, by depth charges from a British Sunderland aircraft (201 Squadron RAF/W). All 58 crew members were lost.

The “Ossett Observer” carried an obituary for Ashley Giggal:2

“Ossett Naval Officer Presumed Dead – Admiralty Communication – In March last we announced that Sub-Lieutenant Ashley Giggal, R.N.R., only son of Mrs. Giggal, 37, Wesley Street, Ossett and the late Mr. Nathan Giggal, for some years the librarian at Ossett Public Library. In October last year, Mr. Giggal, who had been a radio officer with Marconi International Marine Communications Company for ten years, was transferred to the Royal Navy, with the rank of sub-lieutenant. His first ship was H.M.S. ‘Crispin’, an armed auxiliary cruiser of 5,000 tons, formerly of the Booth Lines, Liverpool, on which he held the position of first radio officer. The ship was sunk through enemy action and he has been missing ever since. His mother has now received a letter from the Admiralty certifying that her son is presumed to have died on February 4th 1941.

The Marconi Company have also written a letter to the mother, in which they state: “In asking you to accept our most sincere sympathy with you in the great loss you have been called upon to bear, we trust it will afford you some measure of comfort to know that during the time your son was employed by us, he carried out his duties to our entire satisfaction and his general conduct was all that could be desired. Further, we are authorised by Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty to state your son gave his life for his King and Country equally with those who have made the supreme sacrifice whilst serving in His Majesty’s Forces. Lieutenant Giggal was thirty years of age.”

Ashley Giggal of 37, Wesley Street, Ossett died on or about the 4th February 1941, aged 30 years, on war service. Administration of his estate was granted at Llandudno on the 21st October to Mary Jane Giggal, widow. Ashley’s effects were £675 0s.6d. He is remembered on Panel 10, Column 1 of the Liverpool Naval Memorial. The Memorial is situated on the Mersey River Front at the Pier Head, Liverpool, close to and behind the Liver Buildings and the end of James Street.

Above: The Crispin before it was converted to an armed Ocean Boarding Vessel (OBV)

At the outbreak of the Second World War, it was evident that the Royal Navy would not be able to man all the auxiliary vessels that would serve with it. To deal with the shortfall in manpower, a number of officers and men of the Merchant Navy agreed to serve with the Royal Navy under the terms of a T.124 agreement, which made them subject to Naval discipline while generally retaining their Merchant Navy rates of pay and other conditions. The manning port established to administer these men was at Liverpool.

More than 13,000 seamen served under these conditions in various types of auxiliary vessels, at first mainly in armed merchant cruisers, but also in armed boarding vessels, cable ships, rescue tugs, and others on special service.

The Liverpool Naval Memorial commemorates 1,400 of these officers and men, who died on active service aboard more than 120 ships, and who have no grave but the sea.

The great majority of Merchant Navy men, who did not serve with the Navy, but with merchant ships, are commemorated on the Merchant Navy Memorial, at Tower Hill in London.3

References:

2. “Ossett Observer”, Saturday, 19th July 1941.